Woollen mills: Plans to save 'iconic' Welsh blanket

- Published

Antiquated machinery and an ageing workforce mean the future for Wales' remaining woollen mills is uncertain

The owners of Wales' last remaining woollen mills are finding creative ways to keep their businesses going as they near retirement.

Melin Tregwynt in Pembrokeshire is becoming an employee ownership trust, external and Melin Teifi in Ceredigion is hoping to be taken on by National Wool Museum.

But Welsh blanket expert Jane Beck said most of the mills were not able to find solutions and would soon be gone.

In 1926 there were 217 working mills in Wales, today there are just five.

Jane Beck has an extensive knowledge of the Welsh woollen industry

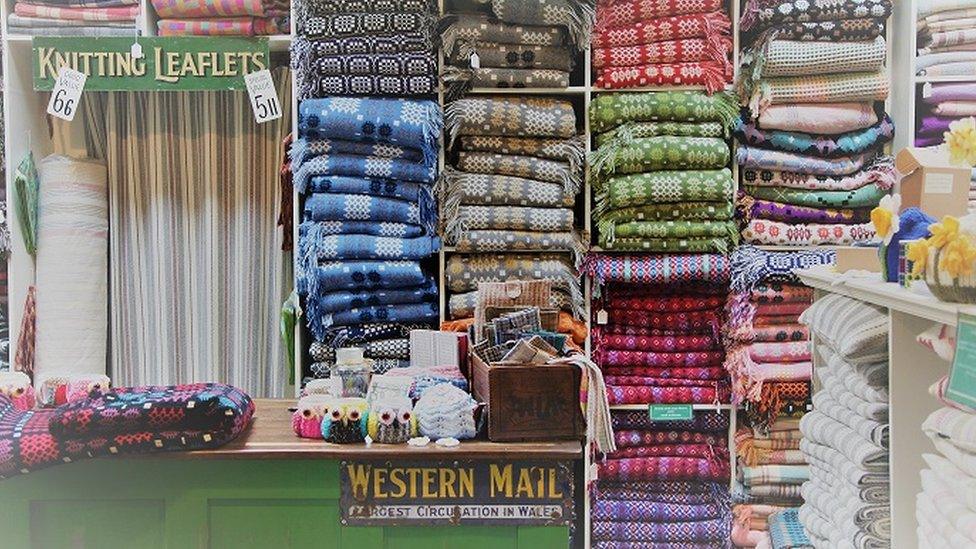

Jane, who has the world's largest stock of Welsh blankets at her shop near Tregaron in Ceredigion, said despite huge demand for Welsh blankets the future of mills was uncertain.

"Most will soon be gone as there is no succession in place and they are not in the same position as Melin Tregwynt to adopt new ways of carrying their business on into the future," she said.

Jane Beck says there is currently "huge" demand for Welsh blankets which is "fast out stripping supply"

She said most mills were "owned and run by an ageing workforce taking advantage one last time of the unexpected resurgence in popularity over the past decade".

"With the exception of Tregwynt, the other mills are using antiquated machinery which are prone to breakdowns and with a lack of experienced people able to repair them," she said.

She said it was possible other mills could open but they would need industry experience and to hit the ground running, adding: "It is not a game for the faint hearted."

Eifion and Amanda Griffiths employ more than 30 people at Melin Tregwynt

Big in Japan

Eifion Griffiths, 67, is the third generation of his family to run Melin Tregwynt in Castlemorris, Haverfordwest.

His grandfather bought the mill, then called Dyffryn, at auction in 1912 for £760 after his wife inherited money from her father.

After training as an architect, Eifion returned home in the '80s to help his parents.

He said he was determined to ensure the mill had a future.

Eifion's father (right) with three visitors to the mill

"We wanted to stay as a Welsh company and we wanted to continue weaving in this part of Wales," he said.

"It is trying to preserve a tradition."

After the UK, the company's largest trade market is Japan: "They understood the power of the story, and the history of product because their own history of craftsmanship is extraordinary."

Melin Tregwynt is in a remote wooded valley on the Pembrokeshire coast

He said the employee ownership trust was a way of ensuring the business does not get sold on and lose its heart.

"If it goes somewhere else the product may not change but the way that it's made and the circumstances around that and the environment might change and we don't want to do that," he said.

"We don't want to preserve it as if it was a museum, but we want to preserve some of the aspects of the traditional way of weaving and this seems to be the best way to do it."

He said their plans meant the business would "in effect be owned by everybody who's working in the business".

Employees will be given shares and bonuses while they are working for the company and the management team continue to run the business as before.

He and his wife Amanda plan to continue in the business for some years but "step back from the day to day and take a more strategic view".

Eifion and Amanda have no children, but Eifion said even if they did they would have been cautious about passing the mill on.

"I would have been very careful not to put this burden on them unless they really wanted it - I've enjoyed it but I don't know many family businesses in the textile industry that have survived as family businesses," he said

Manufacturing at the mill had to stop in the first Covid lockdown but during that time online sales grew.

He said their biggest issue was the supply chain: "Getting the yarn in quickly enough, and making it quickly enough to get it out again."

Raymond Jones started Melin Teifi with his wife Diane in 1981 and they employ four people

'Nobody goes on forever'

Raymond Jones, 76, owner of Melin Teifi in Felindre, Llandysul, has also been grappling with the issue of how to keep the mill going after his retirement.

He has struck upon a different solution - being taken over by its next-door neighbour National Wool Museum.

"I intend to continue for as long as I enjoy what I'm doing," he said.

"Obviously nobody goes on forever so it'd be nice if we planned for somebody to take it over eventually and we're in discussions with the museum, so it is looking promising that eventually will happen.

He added: "They want manufacturing to continue, so I would think that they will eventually be taking it over... we'll see what happens over this next 12 months now."

Museum manager Ann Whittall said: "We have a team of four craftsmen in the museum and we're starting to work with Raymond to make sure we are keeping these skills for the future."

Raymond said the whole industry in Wales faced the challenge of an ageing workforce: "We've all reached a stage where we're getting old, there's not many people are youngsters in this industry."

Despite the challenges he is positive for the future of the Welsh blanket.

"There's sufficient work around now for everyone to be busy," he said.

"I don't think it will die out, there's too much support around... the museum themselves are very supportive, it's part of their history as well and with their support as well I can't imagine that it is going to fizzle out."

'No plans to retire'

Roger Poulson, 72, says he has "no plans to retire"

Roger Poulson's parents started Curlew Weavers Woollen Mill in Rhydlewis, Llandysul in 1961.

The company, which has a staff of five, has been making yarn and woven products for rare breed farmers since the late '90s, "converting the fleece into saleable commodity for them".

"I've got no plans to retire at the moment, my wife says I'll die at one of the machines," said Roger, 72.

He is hoping when the time comes for him to step back his son will take the business on.

"My son helps me at weekends and evenings and runs the mill when I'm on holiday, and hopefully in the future he will be coming in to run it with me," he said.

"He was interested in coming to the mill and I said 'no, you need to see the world and things' because quite often, especially farmers' sons are forced to take it over because there's nobody else to take it on, the heart's not in it and it's purgatory.

"I wanted to make sure he'd seen the world and done some other things and it was really in his blood."

He said weaving was an essential part of Wales' identity: "It is a very important part of heritage in Wales and across the whole UK.

"I'm cautiously optimistic that the business is there.

"I think the rare breed market is growing, I think people are more concerned about natural fibres and sustainability."

Laura Thomas is a woven-textiles artist, designer, maker, curator and lecturer

'Cultural icon'

Bridgend woven-textiles artist Laura Thomas, who works out of her studio in Ewenny, Vale of Glamorgan, has been enchanted by Welsh blankets since she was a child.

"The Welsh blanket is a real cultural icon for our country and is known all over the world - it's instantly recognisable and very recognisably Welsh," she said.

"They're beautifully well-made heirloom products for people to cherish."

She has been impressed by the industry's resilience.

Laura Thomas specialises in producing striking textiles for contemporary spaces

"[They] are really resilient, they have been very resourceful and imaginative and creative in sustaining their businesses, finding new markets, telling the story and explaining the heritage."

She said renewed interest in sustainable and independent products had led to a "burgeoning movement" across the UK for micro mills, with businesses opening in Bristol, London, Glasgow and Liverpool.

Laura said that gave her hope for the future of the industry in Wales: "It's exciting to see, that's what's been happening in Wales for a long time.

"It's really important that we keep the mills working in Wales, so that we can keep telling the story to the market to the audience all over the world."

- Published28 February 2014

- Published25 September 2017

- Published13 September 2020

- Published31 March 2018