Black Boy pubs: Who was the boy in the Swansea sign?

- Published

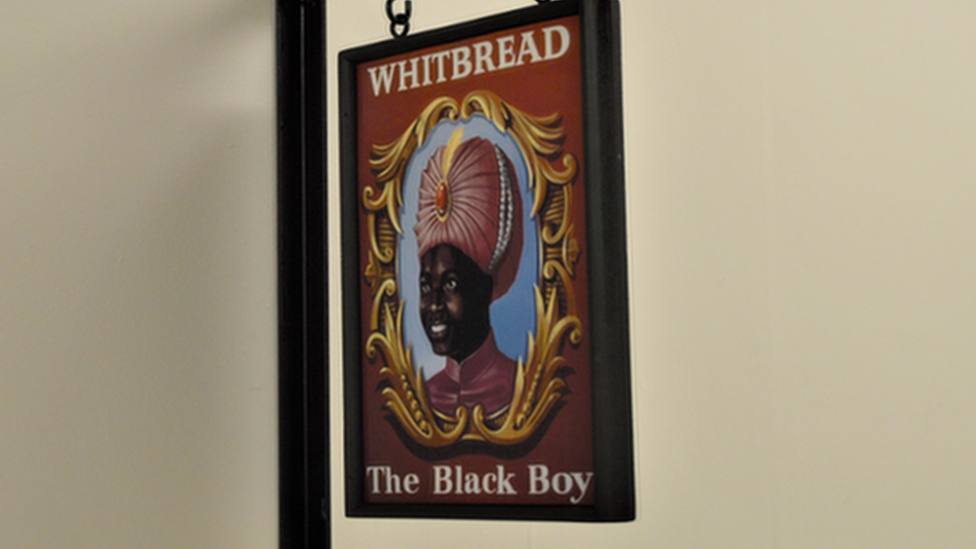

A replica of the original pub sign featured in Daniel Trivedy's artwork Sign of the Times

The image of a boy on a pub sign left such an impression on a young writer that decades later he is still trying to uncover his identity.

Darren Chetty, who grew up in Swansea, said the portrait of a boy in a brightly coloured turban outside the Black Boy pub was "only the third dark-skinned boy I'd ever seen in Killay" in the late 1970s.

"The first time I saw this sign... I was sitting in my dad's blue Mini in the [pub] car park," Darren writes in his essay, "Whatever happened to the black boy of Killay?

"I remember wondering: Who is that boy? Did he used to live here? Was he black in the sense of being African, as the name and his face suggested? Or Indian, as his clothes suggested? What was his connection to the area?".

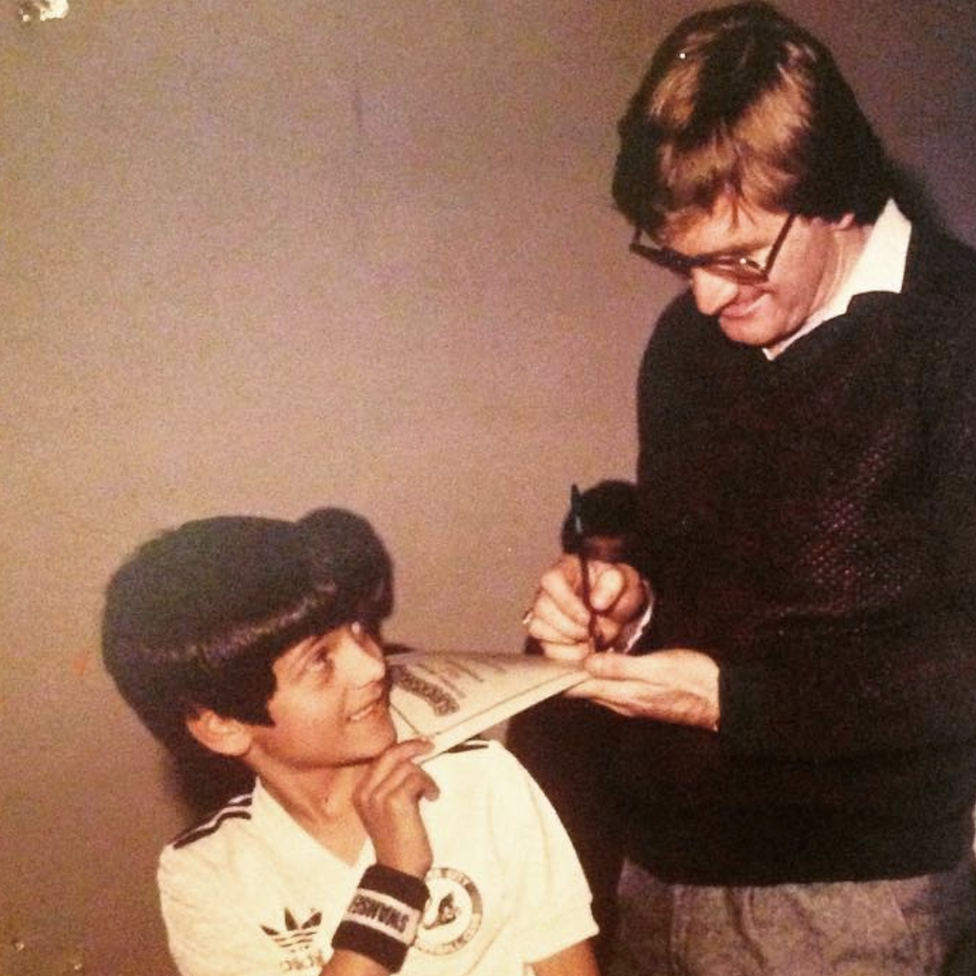

Darren Chetty was born to a Dutch mother and Indian-South African father

Darren, whose mother was Dutch and father Indian-South African, was the first member of his family to be born in Wales.

Growing up in a white suburb, he said his heritage "wasn't something that was continually on my mind... but there were certainly moments where that would become something that I would think about".

In his essay, which appears in Welsh Plural: Essays on the Future of Wales, he recalls first considering whether he was black aged seven after a neighbour used racist language when chastising him.

Darren as a child meeting footballer Leighton James, who played for Swansea and Wales at the time

He recalls another story handed down from his parents, where a nurse used a racial slur when remarking on his appearance after his birth.

Apart from his older brother, a classmate of his brother and the occasional footballer from opposing teams while watching Swansea City - where he witnessed a banana being thrown on the pitch - the boy depicted in the pub sign was the only other dark-skinned person from his childhood.

"I became very interested in [the pub sign] as a child and it sort of stayed with me as I got older," he said.

"It wasn't one of a number of images of black people and people of colour that I was seeing in Swansea, it was kind of the only one."

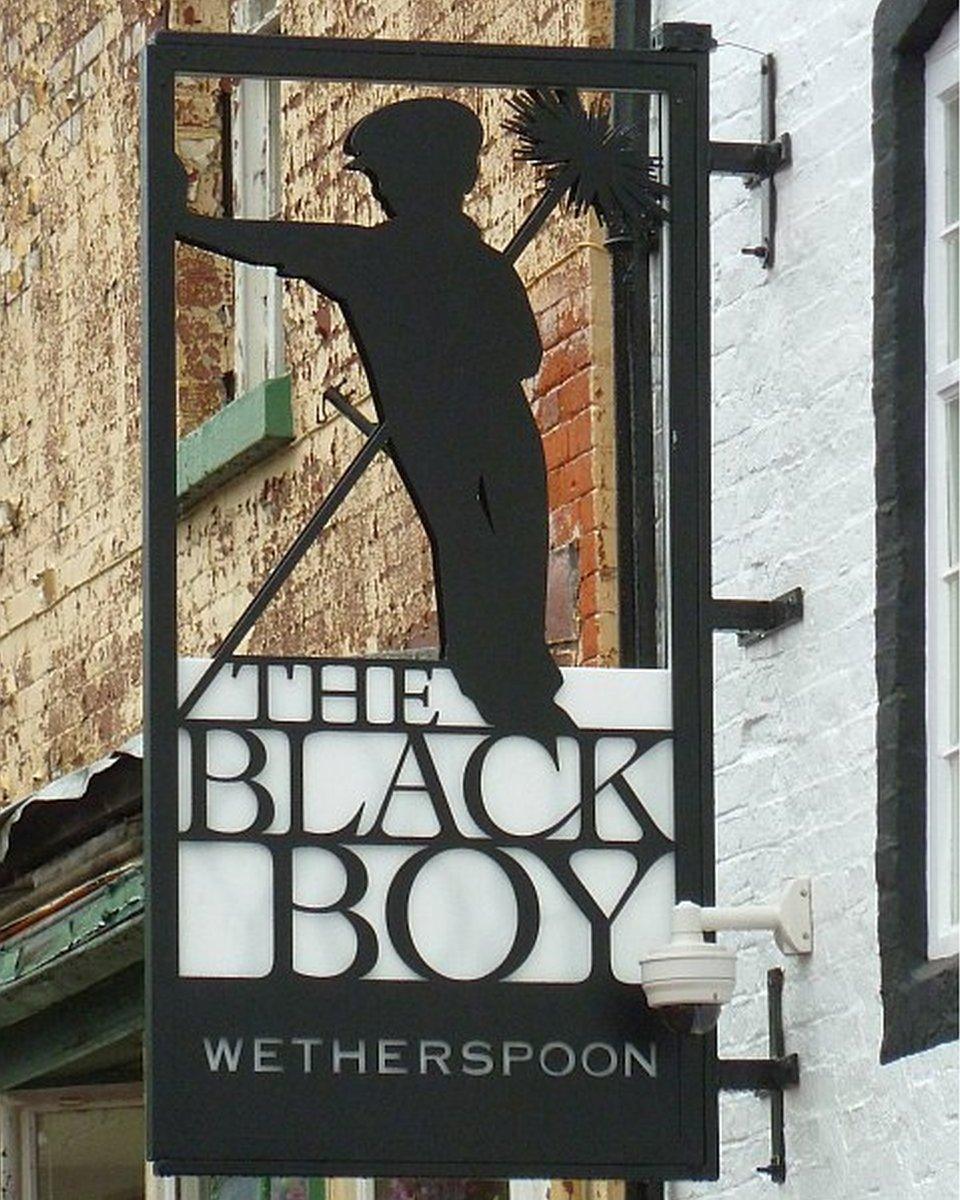

A replica of the Black Boy's current pub sign featured by artist Daniel Trivedy

Today the pub's name remains but the sign has gone - replaced with an image of a white boy in Victorian clothing - but it is an image firmly imprinted on the writer's mind.

There are tens of other Black Boy pubs around the UK, the origins of which are often attributed to a local enslaved African or King Charles II, who was often referred to as having a dark complexion, external.

But who was the particular black boy portrayed on the pub in Killay?

A book discovered in Swansea library offered Darren food for thought.

"In Wales during the 18th Century, it was the height of fashion to employ a black servant," writes David Morris in Black Presence in Eighteenth Century Wales.

"In the popular mindset Africa and the West Indies conjured up images of ivory, Guinea gold, sugar, coffee... a black domestic servant enables the owner to associate him - or herself - with all that was fashionable about the New World. It also brought a touch of African exoticism to the parlours of rural Wales."

Darren also discovered that Swansea's copper industry, which by 1823 supported 10,000 of the city's 15,000 residents, saw copper and brass articles imported as trade goods on the Guinea coast of Africa and eventually acted as African currency.

"Black boys were bought with copper smelted at White Rock [copper works in Swansea]," said Darren.

Historian Prof Chris Evans, from the University of South Wales, also told him Welsh industrialists put hundreds of slaves to work in horrific conditions in the copper mines of El Cobre in Cuba, decades after the abolition of the slave trade in Britain.

The Black Boy in Killay remains but the pub sign has been changed

For Darren, the research brings "black history and Swansea into closer contact than I ever imagined", but still does not reveal the identity of the black boy from his childhood.

"Why was this boy dressed so, so regally?," he asked.

"He didn't look oppressed and downtrodden, he looked potentially wealthy, but then to discover that that wealth would have probably been the wealth of his masters and that he would have been some kind of servant, if not in a position of actual enslavement, changes again the story."

The mystery remains unsolved.

"I wasn't able to get to the bottom of why the pub was ever named that, nobody seems to have uncovered that," said Darren, who is not the only person fascinated by the old Killay sign.

Artist Daniel Trivedy has exhibited an artwork called Sign of the Times, external, which features a replica of the original Killay pub sign alongside the image currently hanging outside the pub.

Writing about the change of sign, he said: "Occasionally people find it necessary to alter the accounts of history to provide a more palatable version of events - perhaps this is the case with the Black Boy pub sign."

He said he originally thought to depict a white boy on the pub sign was to "deprive Wales some of its history and was an advocate for returning to a sign that better reflected its historical relevance", but has since had a change of heart.

"Along with the statues of Colston, Picton and other imperialists, I currently feel that there can be no other option than to remove the sign and rename the pub," he said.

Another artist, Ingrid Pollard, wrote Hidden in a Public Place after 20 years of research into Black Boy pubs.

She writes: "It is my contention that pub signs can be used to tease out hidden histories and heritage stories."

In a BBC Radio 4 documentary, The Mystery of the Black Boy, poet Lemn Sissay visits a number of Black Boy pubs in England.

He concludes the programme by saying: "Personally, I wouldn't walk into a pub called The Black Boy again. I'm a black man and I find the title a little derogatory and belittling."

Marstons, which now operates Killay's Black Boy, has been asked to comment.

There are tens of Black Boy pubs around the UK.

Some other Black Boy pubs have chosen to change the name, such as the one in Shinfield that was renamed The Shinfield Arms in September.

Newtown in Powys has a Black Boy pub

Wales has at least two other Black Boy pubs.

There are currently no plans to change the name of The Black Boy in Newtown, Powys, which owners JD Wetherspoon said takes its name from "the historic name for a chimney sweep".

A spokesman said: "To date, we haven't received any complaints regarding the name, and therefore at the present time we have no intention to change it, but we will keep matters under review."

John Evans has owned the Black Boy Inn in Caernarfon for 18 years

There is also the Black Boy Inn in Caernarfon, Gwynedd.

The pub's owner, John Evans, said he believed the pub was named after John Ystumllyn, an 18th Century gardener who was abducted as an eight-year-old from west Africa and taken to Gwynedd where he became a servant in the household of the Wynn family of Ystumllyn.

He was the first black person in the region whose life was well documented and married a local white woman, Margaret Gruffydd.

He also happens to be the first black person in the UK to have a rose named after them - the John Ystumllyn rose, external.

The Black Boy Inn in Caernarfon has several depictions of a black boy on its signs

Other theories include the pub being named after Charles II or a black buoy from the nearby harbour.

John said: "We're custodians of a 500-year-old pub and I wouldn't like to change anything unless the consensus of the town as a whole said that's what they want."

He said he had received "very few" complaints, adding: "In fact, the amount of black people that stay here and do stay here regularly think it's great."

"I remember one guy coming up the street and saying 'I've got a pub named after me'. They don't see anything racist in it."

He acknowledged some of the many images of a black boy around the inn "do need to be looked at".

"We are looking at that at the moment but the name is important because it's part of history," he said.

For Darren, the issue is not whether the pub signs should be changed or the pubs should be renamed, although he said he believed Black Boy pubs were probably "an anachronism that needs to move on".

He said: "I'm intrigued by the arguments for justifying keeping the names, which is sort of 'it's our heritage', and yet people don't really know what that heritage is - nobody knows why the sign is there."

He said it would "give a very different connotation to an image of a black boy if people of Swansea were aware of the city's history".

"I think there's just a sort of confusion now of what the pub name means," he said.

"To me, when I leave east London, where I live - which is a very multicultural place - and I go to Swansea and I hear people talking about the black boy it jars, it feels odd."

- Published22 February 2022

- Published6 March 2022

- Published10 September 2021

- Published26 November 2021