Falklands War: How creativity helped veterans heal

- Published

Two Falklands veterans describe how creativity helped them through the trauma of war.

Will Kevans was always an artist at heart but he never imagined that one day his talent for creating cartoons would help him make sense of the conflict he and other young soldiers were drawn in to when Argentina invaded the British-held Falklands Islands in 1982.

His mother had wanted him to follow her path to art college but the rebellious young teenager in Aberystwyth had taken a different route after getting suspended from school and "ending up never going back".

After getting a job in a supermarket and "thinking I was rich", everything changed when the job was converted into a youth training scheme, which meant dole money and a small top-up from his employer.

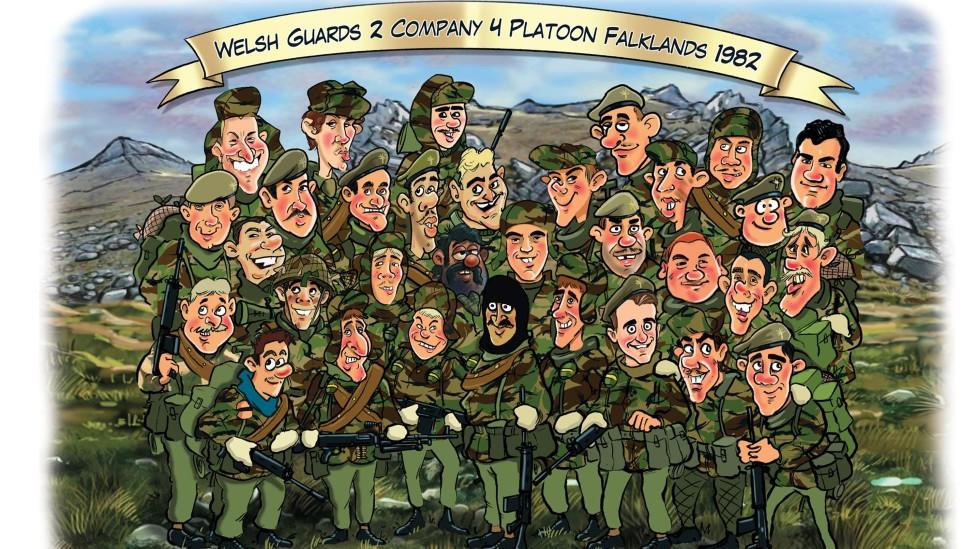

Members of Will's company docked in Sierra Leone on the QE2

With no funds to buy the music and clothing he wanted, he thought: "That's rubbish, I think I'll join the Army."

Less than two years after he was "still playing with an Action Man [toy]" he found himself surrounded by other 18 and 19-year-olds in the Welsh Guards, en route to the Falklands.

"I was as green as they come," he remembers. "I was brought up on an old farm in a cottage and I was naïve, I would say. I was into my music, I loved my punk music, my ska music.

"It was quite bizarre really. None of us really knew where the Falklands was as such. We all thought it was in the Outer Hebrides.

"Logistically it seemed like lunacy for south Americans to come all the way to the Outer Hebrides to conduct warfare against us.

"It was quite a surprise when we found it was off the coast of South America."

On Sapper Hill on the Falklands

After the long trek south aboard the converted cruise ship QE2, one of his strongest memories of war was getting stuck in the middle of a minefield as troops advanced towards the capital, Stanley.

"There was a Marine behind us who was screaming because he'd lost his foot, and he had to be casevac'd (casualty evacuated) out of there," he said.

Mines were set off by soldiers moving over the ground behind them and they all had to take cover. "Suddenly a light went up and we all thought 'this is it now, it's going to be a hail of bullets and end of'.

"We got two guys to get us out of that minefield with bayonets and I think they won a military medal for it. They were combat engineers, literally on their hands and knees, traditional way, probing the ground and it literally took the entire night to get us out of there," he said.

"It was a very scary situation to be in and it was freezing cold and we were covered in snow as well, but we didn't want to move because you thought, if I move I'm going to step on a mine and that's it."

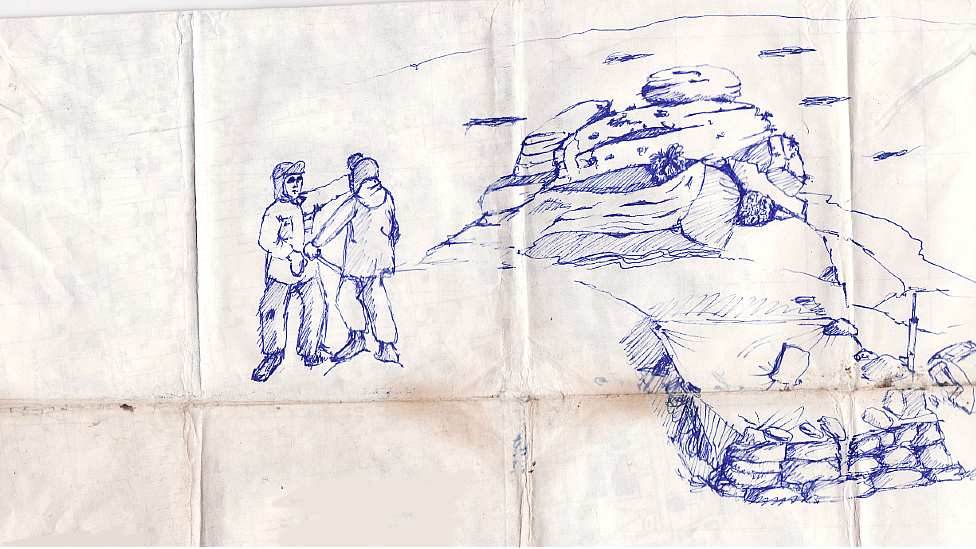

One of Will's sketches done during the conflict

A searing image of the conflict that has stayed with him was the body of a young Argentine soldier his regiment came across on a road after the surrender was announced in June 1982.

Will at work with his sketch book on the Falklands

After he left the army, he had a career which encompassed being a musician, a cartoonist, animator and game designer.

But it was his wife who persuaded him to use his experiences of war when he started to think about writing about parts of his life, initially planning to focus on his time in bands, and it was to cartoons that he turned to tell his story.

"She said, 'why don't you start with the army, because obviously not everybody's been in a war and that's quite interesting'.

"I'd get into a chat with somebody who hadn't been to the Falklands and I'd tell them all these horrific stories, and they'd go 'blimey'.

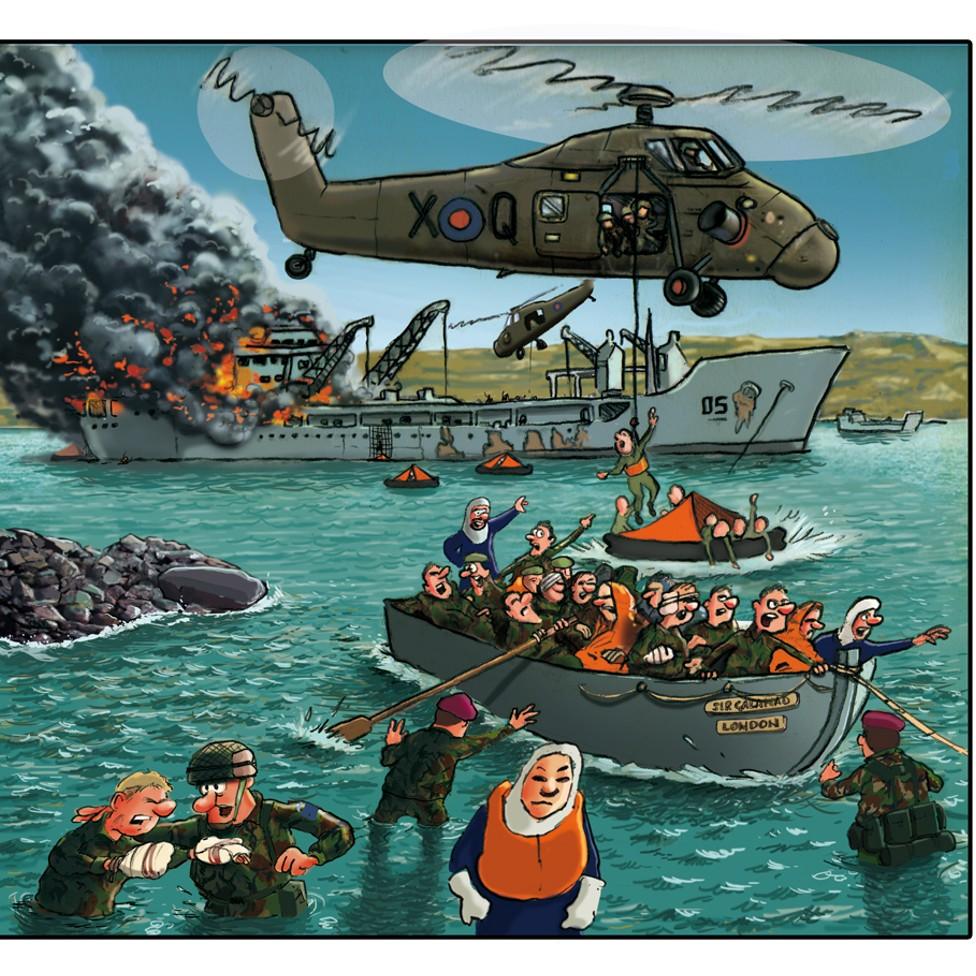

Part of the cover and a page from A Life in Pieces

"I'd be scaring people with all this nonsense and I thought I'd obviously got issues with it, so if I can process it and write about it maybe that will be the way to move forward," he said.

"I had to research it operationally because my memories of it were pretty sketchy. You spend most of your time trying to forget about something because it's an unpleasant experience and then spend all of your time trying to re-remember it."

Talking to people who had had "an unpleasant experience" in the Falklands, as well as dealing with his own memories, was not easy.

But out of the memories came his graphic novel, My Life in Pieces: The Falklands War.

The bombing of the supply ship Sir Galahad, which led to the deaths of 32 Welsh Guards

"When I produced the book, then I found that people were very taken with it, and it helped people process their own feelings on the Falklands. And because it was coming from me, who was a soldier, it was easier for them to take that," he said.

"I think if anybody else had done a cartoon of the Falklands conflict they'd have thought, 'that's a bit tasteless, how can you betray this with cartoons?'

"Well I am a cartoonist and I am a veteran so I can do both of those things."

Nigel hopes a film of his book will use the Brecon Beacons as a stand-in for the Falklands

Reliving his own and other people's experiences in print has also helped fellow veteran Nigel "Spud" Ely work through unacknowledged trauma from his time serving in the Falklands.

A member of 2nd Battalion The Parachute Regiment - 2 Para - when the 1982 war broke out, his regiment was at the centre of one of the most critical battles between Argentina and the UK forces.

The fighting at Goose Green saw 2 Para mount an attack against much greater numbers, who were well-established in a good defensive position, and suffer significant losses but ultimately go on to win against the odds.

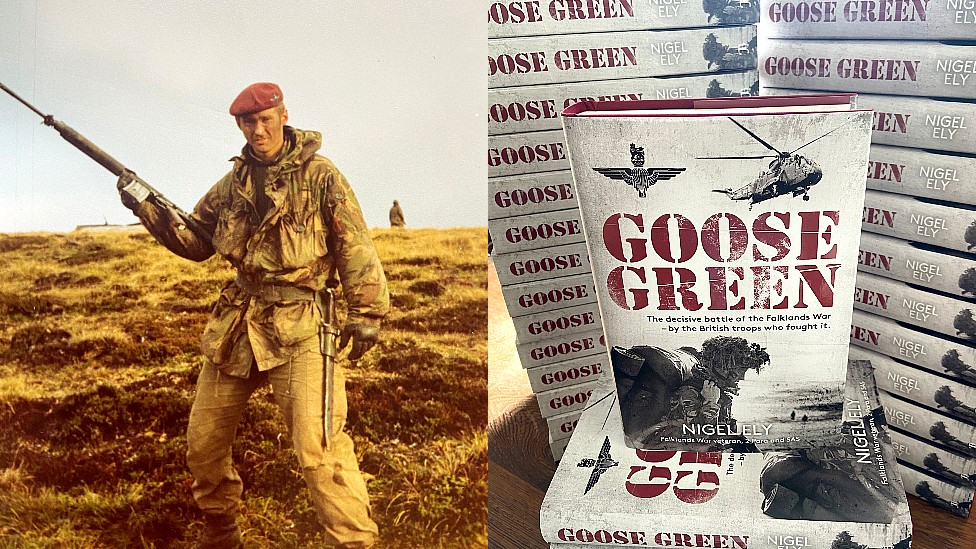

Now the soldier turned author and photojournalist has immortalised the battle in his book Goose Green: The decisive battle of the Falklands War, published to mark the 40th anniversary, and hopes to turn it into a film using Welsh landscapes - which inspired much of his writing - as a setting.

Paras commanding officer Lt Col Herbert "H" Jones was killed in action at Goose Green and awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross

He recalls the arrival on an East Falkland beach as being completely outside his experience.

"We'd never been in landing craft. This was the Royal Marine's business. We were paratroopers, we jumped out of aircraft.

"I do remember being soaking wet, up to my neck in water because the landing craft didn't run up the beach, it had fallen short and we were dropped in the sea," he said.

C Company, which he was assigned to, had to set up the "start line" for rifle companies to begin an assault, after which they were held in reserve.

It was during this first wave of fighting involving his comrades in A Company that "a load of the guys got killed", including the battalion's commanding officer Lt Col Herbert "H" Jones, who was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, the highest military honour.

Another memory is C Company charging downhill towards the settlement of Goose Green as the Argentine forces opened fire.

Goose Green, where a decisive battle took place

"We advanced down, bayonets fixed towards the Argentinians - there were trenches there, they were throwing phosphorous bombs... the enemy were so overwhelming with their artillery, with their support mortars.

"They hit us with everything. The noise was so loud for hours and hours; it was just incredible," he said.

"I think [an outsider would] think it was a battle from the Second World War. We were coming to the end of the 20th century and we were still fighting an enemy with Second World War tactics, with basically Second World War equipment too.

"The Argentinians had better weapons than us, they had better kit than ours."

Following the conflict, Nigel moved on to the SAS (Special Air Service) and remained in the military into the early 2000s, until capture by enemy forces in Afghanistan gave a new turn to his career, taking him into journalism.

Discarded Argentine helmets left behind when soldiers surrendered after Goose Green

He worked as a photojournalist in the Middle East, and began writing tales of his military life, publishing a number of books on the subject.

But it was once he turned to the subject of the Falklands that he realised how cathartic writing could be, and not just for him.

"To write a book initially helped with the post-traumatic stress which I didn't think I suffered with until I started listening to other people's stories.

"I interviewed 114 guys of which I've taken about 350 of their stories, vignettes and tales," he explained.

Nigel Ely's experiences informed the writing of his book, Goose Green

But it was not an easy process at first.

"They were like a resistance to interrogation. They wouldn't give [their stories] to me in the way I wanted them to so I had to develop my journalistic skills into more interrogator skills to get it out," he explained.

"They said to me afterwards, 'I would never have spoken to anybody else about it and I'm so grateful that you did and I'm so grateful that you asked me for my stories'.

"I found that very humbling. I had a few of them in tears. They hadn't given their stories to anyone else."

A grim reminder of war brought back by Nigel from the Falklands

A Londoner by birth, Nigel has spent a lot of time in Wales and, speaking surrounded by the Brecon Beacons landscaped which helped unlock his memories of the conflict, says any film on the Falklands "has to be made in Wales".

"Having known the Brecon Beacons for so long, it actually inspired me, and brought those memories back of the Falklands war.

"The Brecon Beacon National Park is the Falklands less the trees.

"I felt it has to be done in Wales purely because of the terrain, and there's a wealth of talent down here.

The landscape of the Brecon Beacons evokes the Falklands for Nigel

"[The same distance as] from where I'm sitting, I could see Goose Green 800m to my front. This is exactly the same. This undulating, quite unforgiving terrain which you could twist an ankle on as soon as you get up.

"The fact that the Parachute Regiment trains up here and in Sennybridge greatly helped us in the Falklands.

"Pen y Fan and the Brecon Beacons is like a bit of shrine to the Paras because they spend so much time here. They love it."

WILD MOUNTAINS OF SNOWDONIA: Five farming families open their gates and share their lives

LAST CHANCE TO SAVE: Will Millard explores some of Wales’s hidden historic buildings

- Published3 May 2022

- Published4 April 2022

- Published6 April 2022

- Published25 November 2021