Falklands War: Five stories from Wales 40 years on

- Published

Some travelled to war on cruise ships, but the reality hit hard on the Falklands

A short but brutal war that saw Welsh soldiers suffer heavy casualties began 40 years ago on Saturday.

The Argentine invasion of the British-held Falkland islands in the far south Atlantic began on 2 April 1982.

It led to the deaths of 255 British military personnel, three islanders and 649 Argentine soldiers during the 74-day conflict.

Five of the Welsh servicemen who played a central role in the conflict share their stories here.

Tony Davies, Regimental Sergeant Major, Welsh Guards

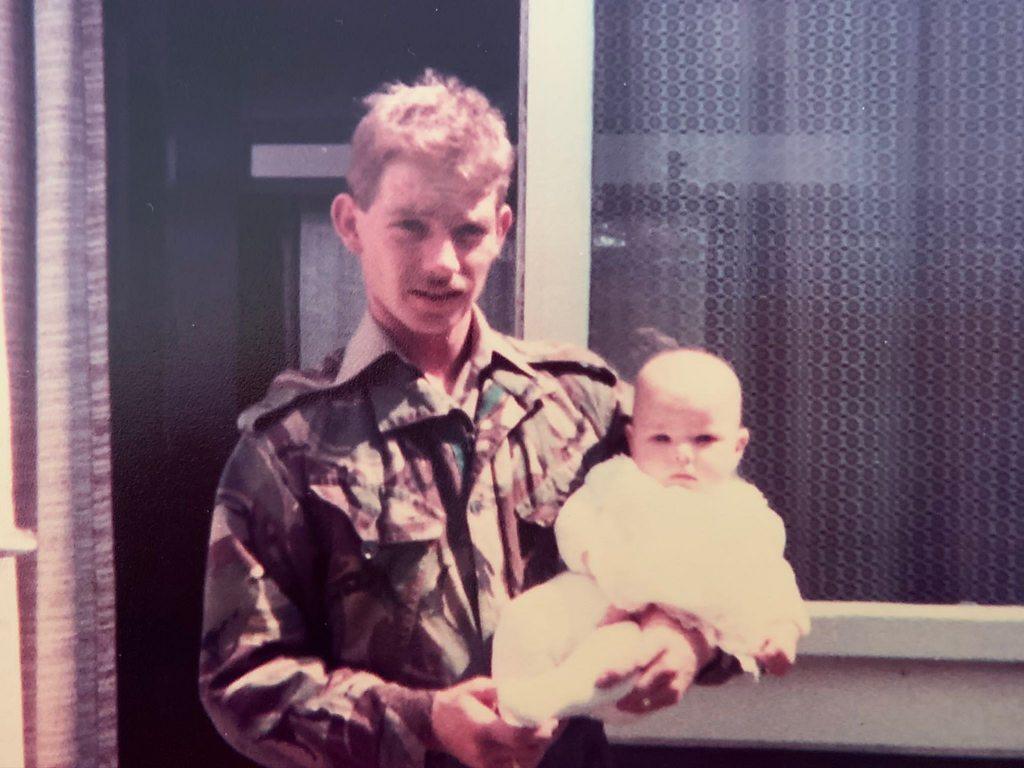

Welsh Guard Tony Davies was light-hearted on hearing he would be travelling on the QE2

Cardiff-born Tony Davies remembers feeling light-hearted when he heard his regiment, the Welsh Guards, were to travel to the south Atlantic with the Royal Marines, Scots Guards and the Royal Gurkha Rifles on the cruise ship QE2.

"Everybody thought, 'Eh up boys, we're up for a quick sailing here, two weeks down to Ascension [Island], enjoy the QE2, it will all be over then we'll turn around, come back and there won't be any war'.

"It was a sort of carnival atmosphere to be honest. I had a cabin on deck two to myself which, you know, we were supposed to be going to war and here am I with the cabin on my own on the QE2."

Five thousand troops were transported on the liner, but Tony, who now lives in Abergavenny, Monmouthshire, did not think they would actually engage in combat until they heard about one of the defining moments of the conflict, the sinking of the Argentine Navy cruiser General Belgrano.

"And as soon as that happened we all thought, 'OK, this is it now, there's no turning back'."

After completing mid-sea transfers to two separate boats, the troops landed at Port San Carlos and took up positions on Sussex Mountain along an air raid run known as "Bomb Alley".

It was a sudden change from the relative luxury of the QE2 but the transition did not faze the troops, as Tony explained.

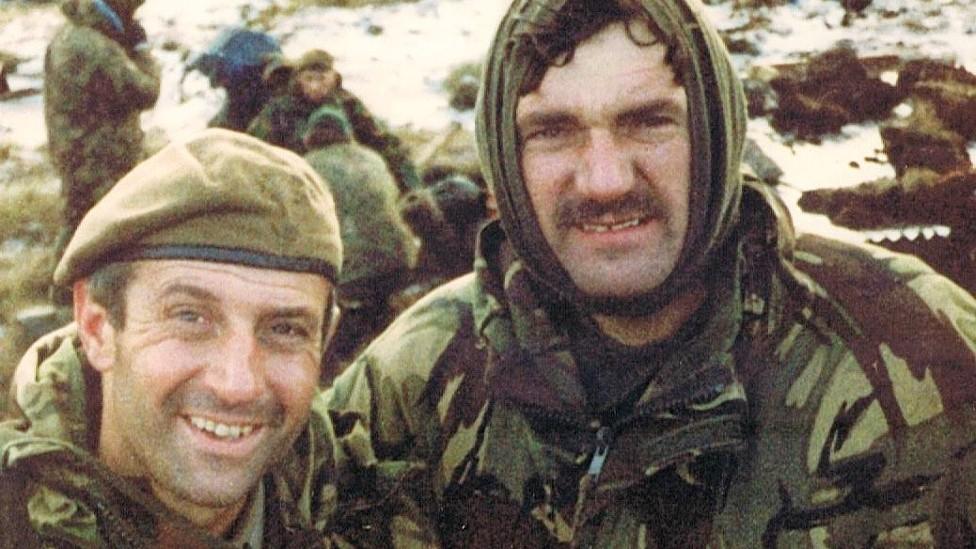

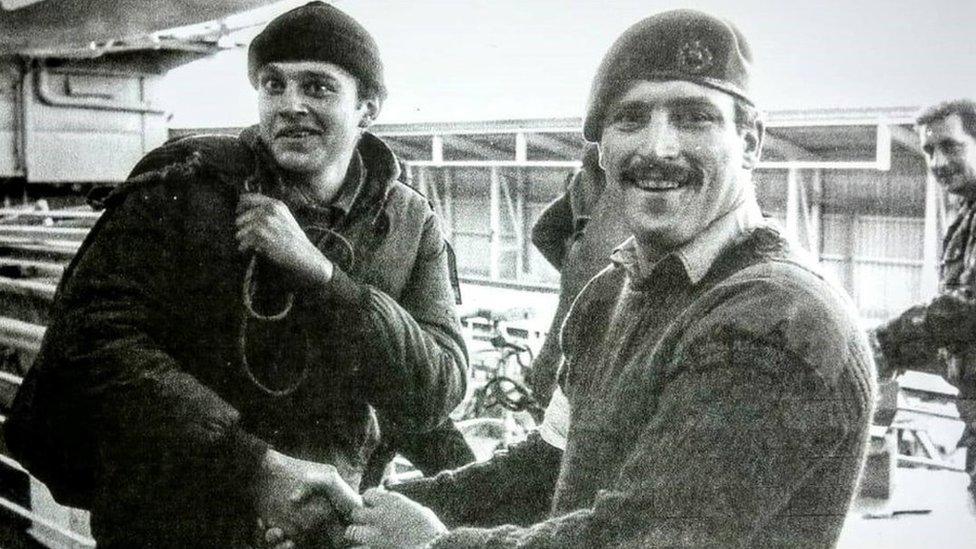

Like many of the soldiers, Tony Davies (right) initially thought they would not see action

"I don't think all the time I was down there, and I don't say this lightly, I saw anybody that was what I would call frightened or afraid of getting involved in any situation," he said.

"We had good briefings on what the Argentines consisted of, what forces they had on the island and reasonably whereabouts they were."

As the British advanced, Tony moved towards the capital, Stanley by sea. Because of a lack of landing craft, only half his battalion could go to shore.

The other half were transferred to two logistics ships he describes as "reasonably unarmed ships".

Survivors coming ashore from the bombed Sir Galahad, helped by people including Tony Davies

One of these ships was the Sir Galahad, which became one of the most vivid images of the war when it was bombed by Argentine forces.

Tony was riding a motorbike with his commander, when they saw the Argentine planes attack.

"We could see there were two ships that were blazing," he said. "We went straight to 2 Company, which we were about half a mile from.

"[We] got straight on the radio and then we got a report to say that our boys were on one of the ships."

His boss "whistled up a helicopter" and they were flown to the shoreline close to the stricken vessels.

"There were guys being lifted off the bow by helicopter winch, because it was the stern of the Galahad where all the damage had taken place.

"The hole was still blazing. There were still explosions, bombs were going off.

"We could see lots of people, lots of our guys on the bow of the ship being lowered down into the life rafts."

At least one bomb had exploded in the hold where the ammunition was kept.

As Tony explained: "We didn't know the numbers, but we knew quite a few guys were injured.

"It took us actually about three days before we knew exactly what was what, who was missing, who was wounded and who we had ashore. So it was quite a difficult time for us, I would say."

Of the 48 men who died on the Sir Galahad that day, 32 were Welsh Guards.

John "Taff" Meredith, Platoon Sergeant, 2nd Parachute Regiment

John "Taff" Meredith described how the platoon was attacked after Argentine troops appeared to surrender

John "Taff" Meredith from Bangor, north Wales, was a soldier with 15 years experience when war broke out on the Falklands.

Part of his role was to prepare his regiment for conflict, and that's what happened on the long journey to the south Atlantic Ocean.

As he put it: "If you do your job properly, and remember your training, you've got a better chance of staying alive.

"You were thinking that if we have to do this, then we're going to do it properly.

"My job was to instil the training in them, instil the fact that they know what they are doing. And two, that if they did the job properly, that they would survive. And that's what we did all the way down."

The terrain that greeted them on the Falkland islands was strangely familiar.

"It looked like Brecon, you know, if you're going up onto the hills there that kind of terrain, very boggy in places, large clumps of grass, you know it's difficult to walk over," he explained.

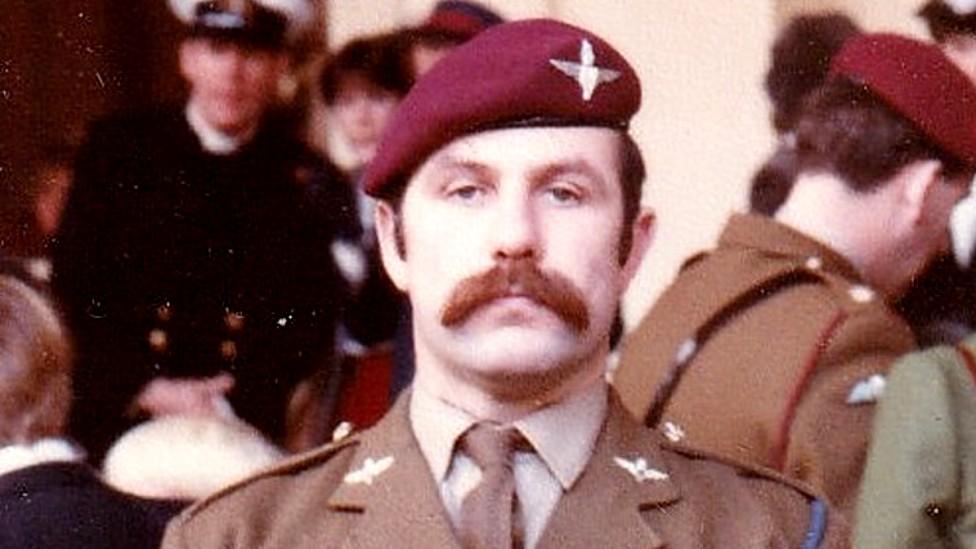

John "Taff" Meredith was a seasoned soldier going into the Falklands war

One of the key battles of the conflict was fought at Goose Green on 28 and 29 May 1982, and John's regiment, 2 Para as it was known, provided the bulk of the fighting force.

The commanding officer, Lt Col Herbert "H" Jones was killed in the fighting and later received a posthumous Victoria Cross for his actions.

Describing part of fighting, John said: "We got strafed by Pucara [Argentine war planes]... then not long after that, another one came in and dropped napalm and that just missed us to the right.

"A Pucara was shot down and I sent two of my blokes who got the pilot... and he was one of the ones that Major Keeble, who'd then taken over as CO, sent in with his ultimatum that night."

Andy "Curly" Jones, Guardsman, Welsh Guards, Prince of Wales Company

Andy 'Curly' Jones recalls the moment the RFA Sir Galahad was bombed

Andy Jones was one of the many Welsh Guards waiting to disembark from the Sir Galahad on 8 June 1982.

"The ship itself is hollow such as a tank deck, like a roll-on roll-off ferry. And inside there was all ammunition and petrol and everything and we were sitting on top of it," he said.

His company was one of the last to disembark. He was climbing a staircase when the first Argentine jet flew over.

"The jet was flying obviously very, very low. We knew automatically that anything flying low was an Argentinian and not British," he explained.

"As one, everybody turned around and started to go back into the tank deck. And in a matter of seconds, the world then turned orange.

"Running into the tank deck, I was immediately picked up and then thrown back out the way I came."

A total of 48 soldiers died on the Sir Galahad, 32 were from the Welsh Guards

Andy remembers a flash followed by an "instant fireball that came through the ship".

The force of the explosion left him in the middle of a pile of bodies.

The ones at the bottom were protected but the one at the top were "much more burnt".

Trying to find a way out, a group of about 20 became trapped in an internal corridor, with explosions at one end and water rising on the floor.

"The thought was, which way do you want to die? That seriously was your decision. Were you going to shoot yourself, because of the water on the floor?

"I'm not a Navy person, I don't know, was the ship going down? Are you going to get blown up? Are you going to drown or do you take that?" he asked.

"And then you were thinking, how will my parents know how I died? That seriously was in my mind. My parents won't know the manner of my death."

Andy, who now lives in Libanus, Powys, was serving with two others from his home town of Carmarthen in west Wales.

They had recently left the town together, returning from a weekend's leave before boarding the QE2.

Andy Jones was on board the Sir Galahad when it was hit

"The other two boys died so three of us from Carmarthen and unfortunately I was the only one to go back.

"The Galahad, as far as I'm concerned is Welsh. Everything about it there with the Welsh Guards and the attached troops as well."

Andy was diagnosed with PTSD in the years following the conflict.

He said the war changed his life: "When you go to primary school with someone, and you grow up on a small estate, you both join the Army together, and you're seven yards away from him, and he dies.

"You both left your home town together. You promise to come home together. Suffering is the least of my problems."

John Callaghan, Leading Marine Engineering Mechanic, HMS Glamorgan

John Callaghan survived a missile strike on the HMS Glamorgan two days before the war ended

A close call with two bombs early in their deployment was a "wake-up call" to mechanic John Callaghan and the rest of HMS Glamorgan.

They had moved in on 1 May to "bombard the shore positions in broad daylight" which he called a schoolboy error.

"I was closed up in the midship section with is one of the damage control positions," he said.

"At action stations, we could hear these things flying over and dropping various things out of the sky and we were straddled by two bombs. It lifted the stern completely out the water," he said.

They were shaken but unhurt, apart from some damage to the stern discovered when the ship docked after the war.

Much worse was to come.

Two days before Argentina surrendered, the ship was providing naval gunfire support for Royal Marine commandos who were attacking Two Sisters, outside the capital, Stanley.

John was on late watch and was on his way back from deck when he heard "what I thought was the decoy launchers firing".

John Callaghan was on HMS Glamorgan which provided naval gunfire support for Royal Marine commandos

He said: "Within a split second there was this thud as the [Exocet] missile hit. I saw a shockwave in the air, guys getting blown off their feet. And there was a sort of silence for a couple of seconds and then the alarms went off and everyone's back to action stations."

There were horrific injuries but everyone had to get on with their own jobs to save the ship.

"We had major fire in the hangar. The helicopter had been hit by this missile and it exploded," John said.

"The helicopter was fully fuelled and fully armed. The fireball went over 100ft in the air."

Quick thinking by some of his crewmates - including one who spotted the missile approaching and turned the ship to present a smaller target, and others who managed to drain floodwater to a lower part of the ship to prevent it from capsizing - saved the day.

But the price was heavy, with companions from his hometown of Cardiff affected. "We had a number of casualties... 13 fatalities on the day. One guy died later when we got back to the UK.

"There was a young lad from Cathays called Terry Perkins who was only 18 and he was in the hangar. And I mean, he must have been killed instantly. That was very sad."

Manny Manfred, Platoon Sergeant, 3rd Parachute Regiment

Manny Manfred described how the Argentine troops reacted to their arrival

When you serve in a regiment with the word parachute in the title, it might be assumed that your expected means of entry to a battle situation would be through the air.

But Manny Manfred and his companions found themselves on the SS Canberra near Ascension Island practising a new skill, beach landings via the sea, ahead of their arrival at the Falklands.

Speaking from his home in Newcastle Emlyn, west Wales, he recalled: "We would flood out onto the beach and then spread out. Totally alien to us.

"We would [normally] either go air landing out the back of an aircraft, we would parachute or some other form of insertion. In my time - I've been in 10 years at this stage - I've never done beach landings."

The fighting, once they reached the Falklands, reminded them of scenes from World War One he recalled, sheltering in trenches using bayonets.

"[At the battle of Mount Longdon] B company took the brunt of the fighting. Initially, they advanced with bayonets fixed.

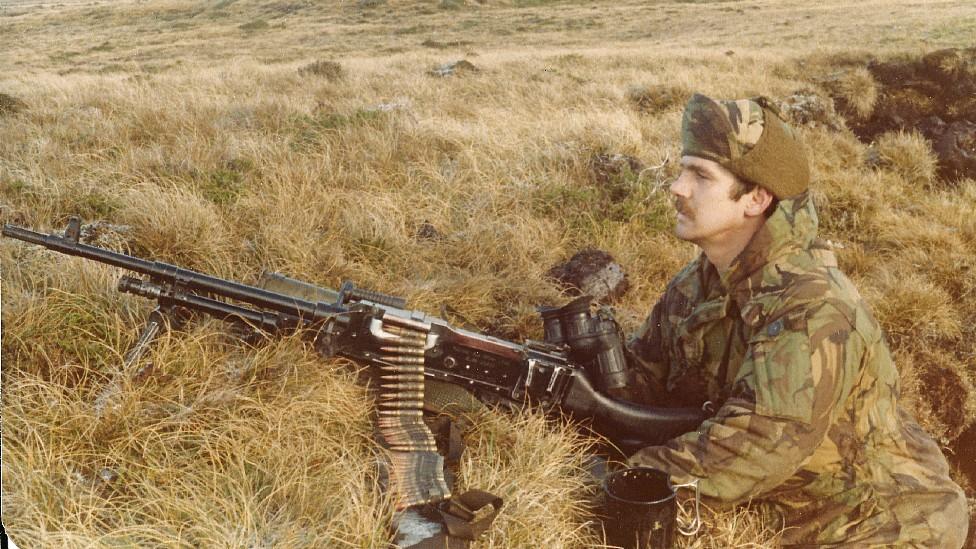

Manny Manfred deployed in the field of combat on the Falklands

"And with bomb, bullet and bayonet they were attacking each of the Argentinian positions.

"There'd be two-man teams, fire team, one firing while one would be manoeuvring, locating the enemy using grenades in there to winkle them out of those positions, and of course engaging in many cases in hand-to-hand fighting."

When the Argentine surrender came, there was a race between different groupings to be the first into Stanley.

"When you looked around in the broad daylight you could see British troops flooding off the features. To our left, [on] Wireless Ridge were 2 Para, our sister battalion.

"To our right [on] Mount Tumbledown, Scots Guards, and it was decided that regimental pride dictated we wanted to be the first into Stanley," he said.

"So helmets came off, red berets came on. And it was just like a practice tab [tactical advance to battle, a fast march carrying a heavy pack], where you had to do your 10-mile tab in one hour 40 minutes back in Aldershot as part of your annual qualifications.

"Yeah, head down, bum up and into Stanley."

SURVIVING HELMAND: Inspirational stories from those deeply affected by the conflict in Afghanistan

TIP NUMBER 7: The families of Aberfan fight for justice

- Published20 January 2022

- Published20 January 2022

- Published10 January 2022

- Published3 January 2022

- Published8 November 2021

- Published14 September 2015

- Published14 September 2015