Terrence Higgins: A name that gave hope to those with HIV and Aids

- Published

'Incredibly funny, a complete daredevil and very Welsh'

You may have heard the name and might know his legacy, but perhaps don't know who Terrence Higgins really was.

He was a charismatic, fun-loving guy, loved by his group of close friends, yet it was only after his death that his name became known the world over.

Few know of his unique "wiggle legs" dance, the astrology book he wrote and that his sexuality was behind his move to the city where he could be himself.

Terry, as he was known, became famous for how he died, but he also lived.

His name is now synonymous with the fight against HIV and Aids, because Terry was the first named person in the UK to die of an Aids-related illness.

No-one had heard of the virus HIV when he passed away aged just 37 at London's St Thomas hospital on 4 July 1982 - and very few people had heard of him.

A name known around the world

But those close friends who knew him so well were determined to not only change that, but also change the way the world dealt with an illness few then knew much about.

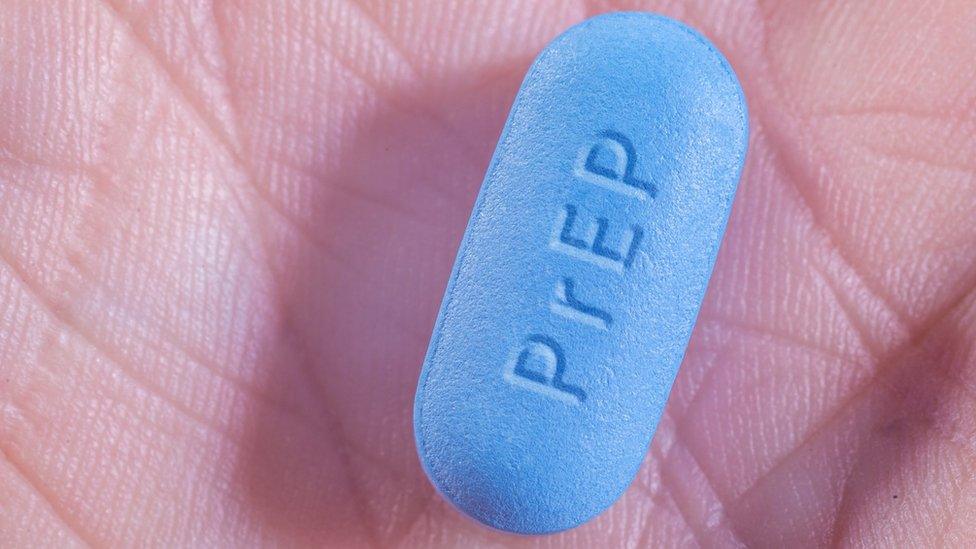

Superstars and royalty now regularly support the charity that immortalises a man whose death became the unfortunate catalyst for medical research and subsequent treatment that now ensures the illness that ended Terry's life is no longer considered a death sentence.

Meghan Markle and Prince Harry's first public appearance together as an engaged couple was at a Terrence Higgins Trust event

Within 10 years of Terry's death, proceeds of two musical anthems - Queen's Bohemian Rhapsody and Don't Let the Sun Go Down On Me by Elton John and George Michael - were donated to the Terrence Higgins Trust.

It's gestures and support like this, alongside work to help people with HIV and promote good sexual health, that has helped the organisation that carries Terry's name become a world-leading HIV charity.

'Terry had a dancer's walk'

The journey began just before the end of World War Two, in June 1945 in west Wales.

Terry was born in the old Haverfordwest workhouse when it became a unit of the local hospital

Terrence Lionel Seymour Higgins was born at the old Priory Mount workhouse in the market town of Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, to Marjorie - Terry's dad wasn't on his birth certificate.

It was in the town's dance halls as a teenager, that school friend Angela Preston remembers him.

Terry was renowned for his dancing... some friends called it "dad dancing" while others called it a "wiggle"

"He would say to me and my friend 'come on girls, up you get', and he'd jive with two of us at the same time," she told BBC Sounds A Positive Life podcast, narrated by singer Sam Smith.

"He was brilliant. I can see him coming down the high street now and his trousers would be flapping. He had a dancer's walk. They have that airiness, that floating movement.

"To me, he was just Terry who I danced with on a Saturday night.

Sam Smith has narrated a BBC sounds podcast which chronicles the life of Terrence Higgins

"He had this air about him, he wasn't repressed, he got on with life and seemed to enjoy everything he did - and by heck he had a lovely smile. He was a lovely boy.

"It was only when he died that I found out that he was gay. I was quite shocked because I didn't have an inkling."

SAM SMITH PRESENTS STORIES OF HIV: From Terrence Higgins to today

BORN DEAF, RAISED HEARING: What it means to live in two different worlds

He was a quiet boy growing up'

When Terry was growing up in the 1950s, gay sex between men was illegal and you could be sent to prison. These laws only began to change in 1967 - even then only partially.

Bill Yabsley was a few years younger than Terry and said growing up, he was a "quiet boy"

"We'd play out in a field which was part of the council estate and occasionally Terry would come down," said Billy Yabsley, a neighbour who lived on Terry's street Priory Avenue.

"I was, say 10 and he was 14. He wasn't really a mixer. It was very rare that Terry came out.

"We were rough and ready kids, cricket one minute and football the next, then falling out and fighting - but Terry never got involved with any of that, he was a quiet boy.

Priory Avenue in the Pembrokeshire market town of Haverfordwest is where Terry grew up

"I used to go to market hall and they'd turn it into a dance room and I can remember him dancing, he was out of this world. We were like farmers in boots but when he danced, he was light like a ballerina and used to sway his body."

'Difficult'

Terry also used to play the piano and Bill remembered "he was a very talented boy" who was a decent schoolboy athlete at the strict Haverfordwest Grammar Boys School, where he won the senior long-jump competition in the late 1950s.

Terry started life in west Wales at a time when coming out as gay to friends or family could be considered a risky choice as attitudes towards homosexuality were different.

"I would have thought it would have been dreadfully difficult because there was such a stigma attached," Angela added.

Haverfordwest is an old market town on the banks of the River Cleddau near the western tip of southern Wales

After finishing school in the early 60s, Terry left Haverfordwest to join the Royal Navy and lost contact with his old school friends - but not before donating his books and stationery to the school library.

'So handsome with creases in his trousers'

"We would often get visits from Terry when he was in the navy," said Terry's cousin Annie Oakley, who now lives in Australia.

"I thought he was so handsome because he had very dark hair and had creases in his trousers because of how they used to fold them over when they were in the navy.

Terry (right) with his trademark moustache enjoying the sun with friends

"My earliest memory was when he came to visit us and he was in the front garden, swinging us around... and letting us dance on his feet because he was always dancing."

'Oblivious'

As far as Annie knows Terry - an only child - never came out to his family, but he did not completely hide his life from them.

"When I was about 14, I stayed at auntie Marj's and Terry was visiting and he had a friend," she recalled.

How Princess Diana helped changed attitudes to Aids

"It never occurred to me that he had sexual preferences and she said 'can you take this cup of tea up to Terry and his friend'.

"I walked in the bedroom and there were these two males in bed, Terry and his friend, and I just said 'here's a cup of tea'. I was oblivious."

'Great fun and humour'

Terry returned to his home-town occasionally to see his mum before she died in 1974.

"He didn't talk about his family much," said Linda Payan, one of Terry's few close friends from his life in London to return to Haverfordwest with him.

"His mother was a female version of Terry, you could see they were mother and son. Great fun and she had similar humour to Terry.

Sir Elton John is a patron and big supporter of the trust set up in Terry's name

"She could be cutting and he could be quite rude to her, but she'd be rude back. They'd have that kind of relationship. It wasn't really close but they enjoyed each other's company."

'Nothing was said'

Linda said she imagined Marjorie knew her son was gay because she once went back to Terry's childhood home with him and his then boyfriend - but "nothing was said".

"She'd have kept that silent, it was a different time and wasn't an accepted thing," added Linda. "It was very taboo."

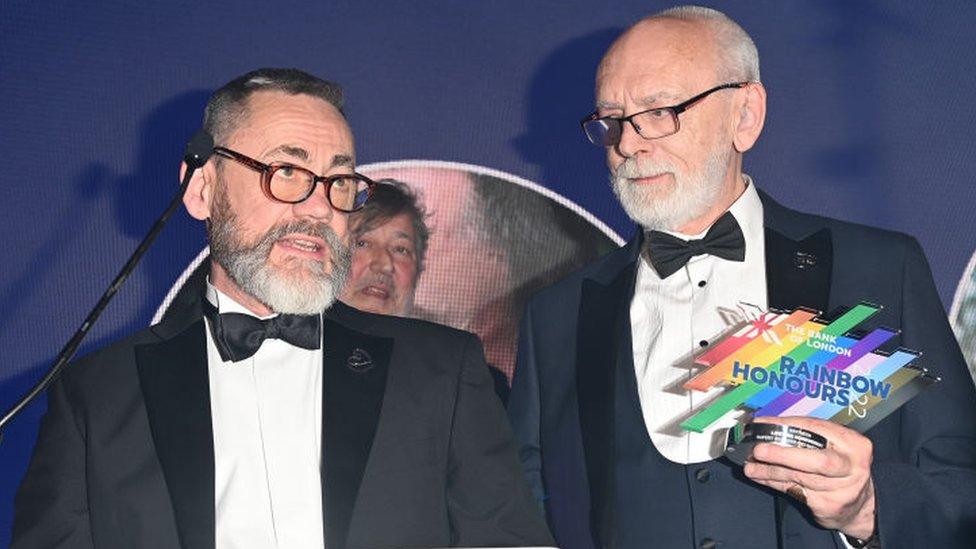

Terry's old friends Rupert Whitaker and Martyn Butler have received OBEs for their work in helping research into HIV

Terry had, by this time, made London his home where he'd enjoy dancing to disco music and felt free to live how he wanted - which could sometimes be like a wheeler-dealer.

"Terry was either with money or without money," added Linda, who first met Terry in a Wimpy fast-food restaurant after a night out in 1969.

"When he was without money, I'd see more of him because he'd have jewellery to sell. He'd say 'can you give me some money for them?' and it'd be a fiver or a tenner for all this silver.

"But he was very kind. Whenever he had any money, it was for everyone."

'Paranoid'

Terry worked for newspapers and wrote for Hansard, the official report of every parliamentary debate in the House of Commons - meaning he worked in the place that had made his sexuality a crime.

Terry worked at the Palace of Westminster on Hansard, the official report of all parliamentary debates

"He was a bit paranoid about being found out to be gay," recalled Linda.

"Once he said 'I've got some people from work coming over for dinner, could you pretend to be my wife?' So I did."

Terry, a Gemini, had an interest in astrology and wrote a book on the subject called The Living Zodiac and he loved socialising.

"I used to call him wiggle legs," added Linda. "He had these wiggly legs when he danced and it always made me laugh... his legs never seemed to part but his knees were together.

"Life was so exciting for him, he was always looking for new adventures and was very funny.

Volunteers for the Terrence Higgins Trust help promote good sexual health and support thousands across the world

"I said to him 'you're either going to be very famous or end up on a park bench'. He laughed his head off on that one. But Terry did become famous."

Where friends were family

It was in the gay clubs where Terry became friends with Rupert Whitaker and Martyn Butler - two men who would ensure the name Terrence Higgins would one day become famous around the globe.

"I liked him because he looked out and cared for people," said Martyn, who was 20 years younger than Terry.

Stephen Fry is a long-term patron of the Terrence Higgins Trust and hosted the comedy revue Hysteria 3 in support of the charity in 1991

"If you were misbehaving, he'd tell you off. He was a bit motherly like that."

Rupert was 18 when he started a relationship with Terry and was enamoured with his streetwise nature in a time where their community felt marginalised.

"He didn't care about anything, he was completely unselfconscious," said Rupert.

"He had a very healthy attitude of scepticism towards any pretentiousness.

Terry, Rupert and Martyn would frequent London's many nightclubs like Heaven, where Terry collapsed twice before his death in 1982

"I thought he was just gorgeous. This was the era of the clones... very short cropped hair, big moustache, strong five o'clock shadow, plaid shirts, tight jeans and builder's boots.

"It was a hyper masculine look and I completely fell for it."

They all became a "family" in a community in London that already felt on the outside - and it was about to get even more tough.

Unknown epidemic

Both had HIV when they met, but neither were to know.

While no-one knew it yet, the wave of this epidemic was about to hit.

Terrence Higgins Trust patron and former Wales rugby player Gareth Thomas revealed he has HIV so he could "empower people"

Within 18 months of their first meeting at Bangs nightclub on London's Tottenham Court Road, Terry had died.

"He never really talked about it," Rupert recalled. "It was like he was a very passive witness to his own deterioration."

In the spring of 1982, Terry's illness became much more serious and he collapsed in London's Heaven nightclub and was rushed to hospital.

"Only family could visit," said Rupert. "I said 'he doesn't have any family, I'm his boyfriend' so the nurses were cool with that, but the physicians didn't talk to me.

'Gay cancer'

"At the time, a gay newspaper ran this report... about what was then gay cancer and pneumonia. We had an idea that this thing was in America but nobody had any idea it was in Europe.

"I was pretty sure that's what Terry had. He'd gone downhill so quickly."

Terry died in St Thomas' Hospital on the banks of the River Thames - opposite his old workplace, the Palace of Westminster

Rupert had been celebrating independence day with some American friends on 4 July 1982 when he popped in with some "ice lollies, Lucozade and Tizer" to see Terry.

Those drinks remained undrunk. Terry died that evening.

'Lifelong impact'

"I knew very much that I had loved him - but I didn't know if he'd loved me," Rupert admitted.

Film star Dame Judi Dench is a big supporter and patron of the Terrence Higgins Trust

"I had to ask a couple of his friends and they looked at me as though I was crazy because they said 'oh yeah, very, very much'.

"Just before he died, apparently he was calling out for me. It's a real regret that I was late.

"The impact that had on me for the rest of my life has been incredible - it changed my life. And hopefully I've done useful with it to help somebody else."

The Terrence Higgins Trust was formed in Martyn Butler's old flat in East London

At the time, doctors were unsure how to diagnose or treat the new illness while there was fear within the community and wider public as to what this condition was.

Within weeks of Terry's funeral, a group of pals who had nowhere to channel their grief and wanted to help fight this unknown illness formed a trust in Martyn's front room in Limehouse in East London.

"I had this sense that I'm expected to be dead already," recalled Rupert.

"I am expected to die. I expect myself to do die. What do I do? Do I just sit around and wait for this to happen or do I actually do something with the time I've got."

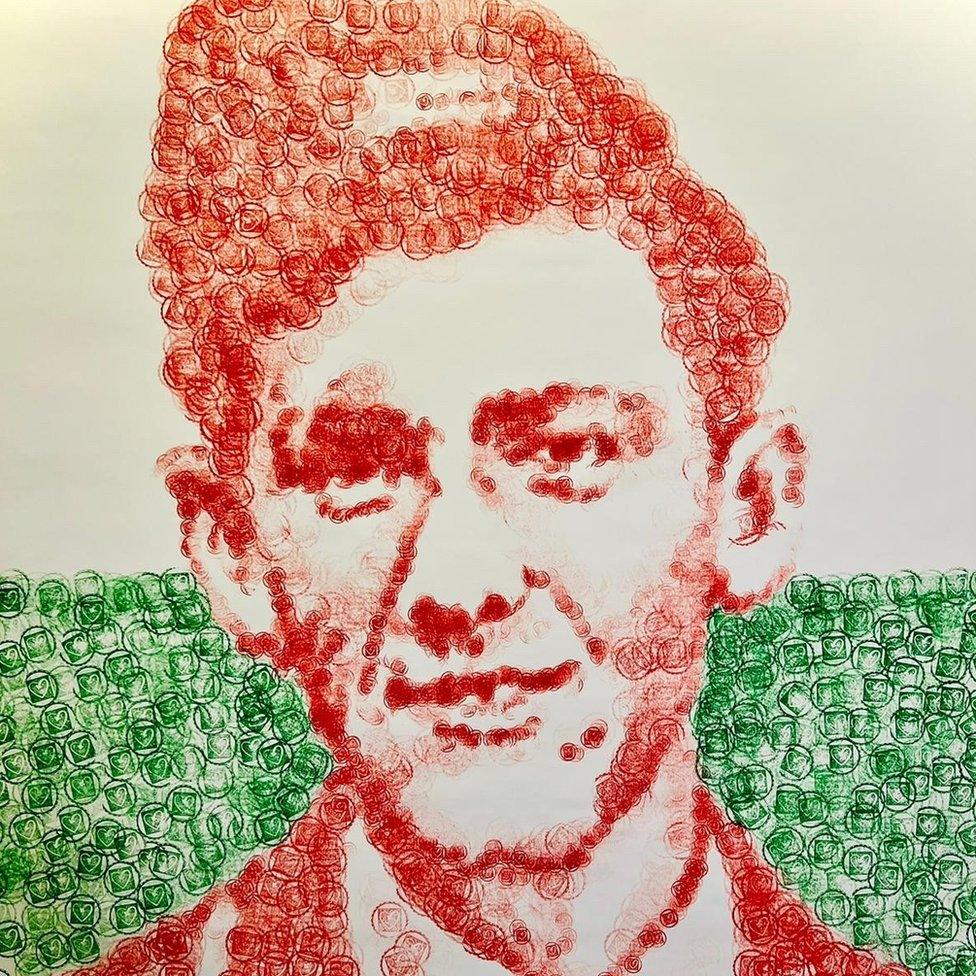

A new portrait of Terrence Higgins is now on display in the Welsh Parliament building in Cardiff

Personalising the trust in Terry's memory, they thought that would give their cause greater impact.

The Terrence Higgins Trust has since helped thousands and provided sexual health services like HIV testing, making it one of the world's oldest and leading HIV and Aids charities.

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this story, the BBC Action Line has links to organisations which can offer support and advice

- Published14 June 2022

- Published1 February 2022

- Published1 December 2021

- Published23 November 2021

- Published18 November 2021

- Published15 March 2020

- Published11 January 2019

- Published5 July 2012