Cuban Missile Crisis: The Welshman who prevented nuclear war

- Published

When Soviet Russia threatened to place missiles on Cuba, President John F Kennedy wanted to see one man, Welshman Sir David Ormsby-Gore (Left of Kennedy)

When the world was on the brink of nuclear destruction, one Welshman held his nerve and arguably saved the world.

In October 1962, Soviet Russia tried to install weapons on an island in the Caribbean, an event that became known as the Cuban Missile Crisis.

The weapons could have destroyed the United States and so President John F Kennedy blockaded the country.

Welshman Sir David Ormsby-Gore, the then-British ambassador to Washington, managed to keep the president calm.

As America surged ahead in the nuclear arms race, the Soviets felt as though their only option for a pre-emptive strike on the West was to base intermediate missiles on Cuba, just 80 miles off the US coast.

On 22 October President Kennedy was summoned back to the White House and his first orders were: "Get Ormsby-Gore there without anyone seeing him."

By the time Air Force One touched down, Sir David - who would later become the fifth Lord Harlech - was waiting in the Oval Office.

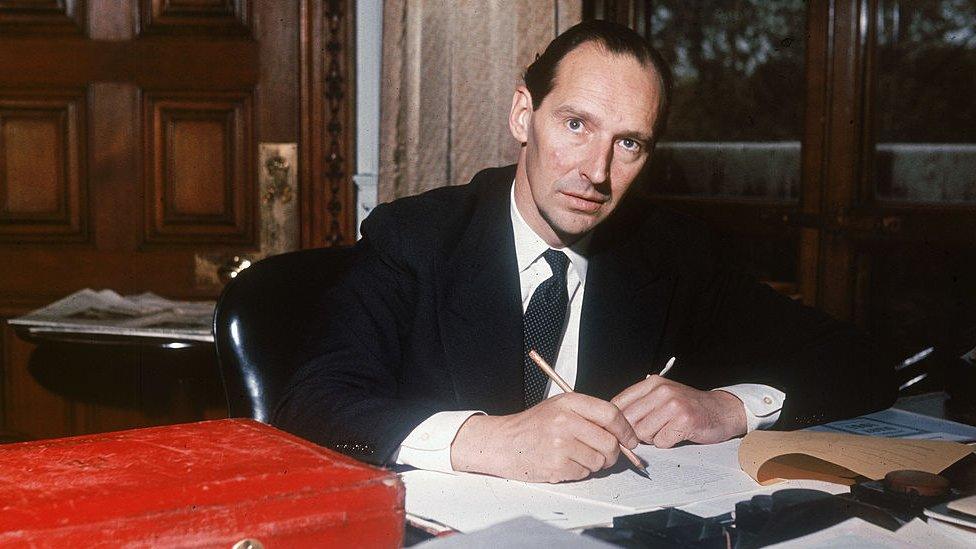

Sir David Ormsby- Gore served as an MP before being asked to take up the role as ambassador to Washington

Mr Kennedy's Vice-President Lyndon B Johnson wrote: "I was there, with the door hitting my chair at the bottom end of the table, and there were those two, poring over maps and whispering to each other at the other end.

"Why was this Welshman even in the room?"

The answer went back to 1938, when JFK's father, Joseph Kennedy, had been US ambassador to London.

Gary Ginsberg, lawyer to the Clintons, journalist, historian and author of First Friends, an account of the people who have most influenced US presidents, said it was a partnership long in the forging.

"In the '30s both were second sons, neither had an expectation of greatness on them, but they'd both lose their elder brothers to war and a road accident," said Mr Ginsberg.

"However, at the time all they had to do was to find a friendship based on conversation, golf, horses and politics."

Jackie Kennedy became very close with Sir David after Kennedy's assassination

Mr Ginsberg describes how the pair would both sit in the public gallery of the House of Commons in order to hear Winston Churchill speak.

"They stayed in touch throughout, as Kennedy became a congressman and Ormsby-Gore an MP.

"I suppose it was a no-brainer when [Harold] Macmillan asked him to take the Chiltern Hundreds, external [resign as an MP], and become the UK ambassador to Washington."

On 23 October they sat up all night, with Sir David studiously avoiding calls from then-Prime Minister Harold Macmillan.

Kennedy had set up a shipping embargo around the island, yet the Soviet boats, carrying ever more missiles, steamed towards Cuba.

President Kennedy set up an 800 mile shipping embargo around Cuba, one Sir David suggested shrinking

Mr Ginsberg said it was Sir David who then made a suggestion which many at the time saw as weak, but which in hindsight was one of the world's great pieces of diplomacy.

"'Why don't you shrink the embargo from 800 miles to 500?'"

He argued this would give the ships' captains, and the Soviet leaders, greater time to think of the consequences of what they were doing.

It worked. On 29 October the Soviet ships turned for home.

Under Sir David's guidance, the two super powers went on to establish the "hot line", a direct communication to ensure tensions could never again reach that level without the two leaders speaking.

The US also withdrew missiles from Turkey and an arms reduction treaty was forged.

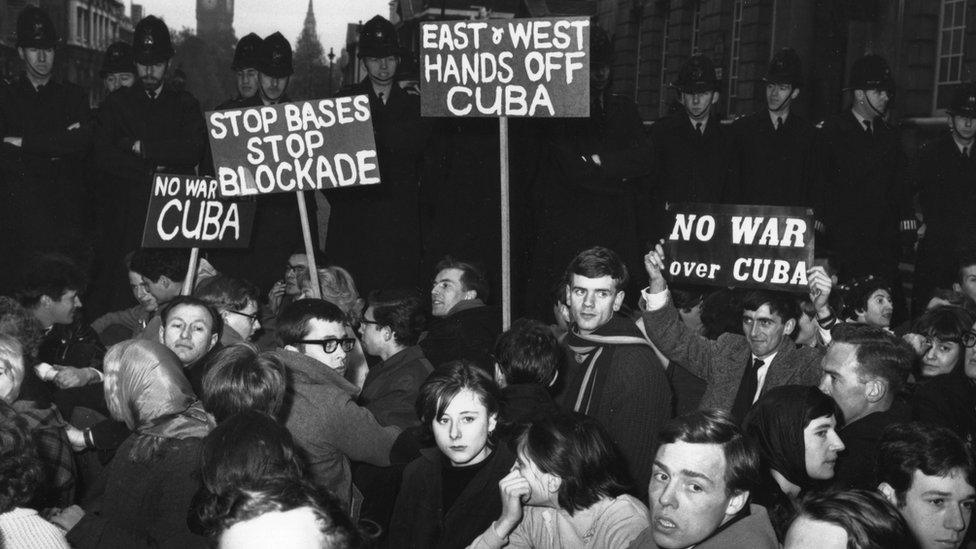

Protests erupted in the UK following the Cuban Missile Crisis, which almost triggered nuclear war

Just a year later, Mr Kennedy was assassinated.

Now Lord Harlech, Sir David would go on to have a profound influence on the Welsh media scene as chairman of the British Board of Film Classification and Founder of HTV.

In 1968 he proposed to JFK's widow, Jacqueline Kennedy, and although she turned him down, the two remained good enough friends that she would attend his funeral in 1985.

Also among the mourners was JFK's brother, Teddy Kennedy, who said his mother Rose had described Sir David as "another son to me."

WHO DO WE THINK WE ARE?: Huw Edwards explores the source of Wales' identity

WALES ON AIR: A unique concert reflecting life in Wales

- Published7 October 2022

- Published22 November 2016

- Published29 March 2017

- Published2 March 2017