Conversion therapy ban will be hard to police, says victim

- Published

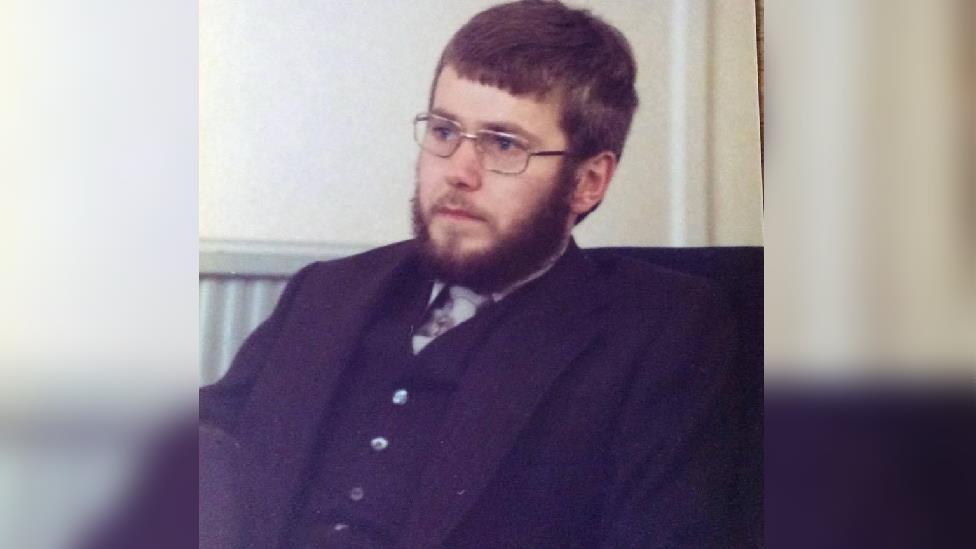

John Sam Jones says electric shock aversion therapy closed down his sexual response rather than changing it

A man subjected to electric shock aversion therapy in the 1970s to stop him being gay has welcomed plans to ban conversion therapy.

But John Sam Jones, 67, who grew up in a Christian home in Barmouth, Gwynedd, cautioned that it would be "a nightmare" to police.

The UK government has announced plans to outlaw all forms of conversion therapy in England and Wales.

Several religious groups have defended the practice.

The UK government said it would publish more details of how the ban will protect those at risk in due course.

Mr Jones said attitudes to homosexuality were still incredibly negative during his youth in the 1960s, despite it being decriminalised in 1967.

He said: "Homosexuals were imprisoned, it was said they were a danger to children. By the time I was 18, I had absorbed all that negativity and I thought I was mad, bad and sad."

This story contains details some readers may find distressing.

John Sam Jones said at 18 he was "terrified of being what I was", and did not want to be gay

Mr Jones started having suicidal thoughts and sought help from a psychiatrist who claimed he could "cure" his sexuality using electric shock aversion therapy, external.

"I agreed to it because I was terrified of being what I was. I didn't want to be gay," he said.

'Bona fide treatment'

The therapy meant hooking him up to electrodes and showing him gay porn - if he got an erection, he was electrocuted.

He said he was meant to have been fitted with a device on his penis to measure his reaction, but the hospital he was at in Denbigh did not have one so he was naked from the waist down.

Mr Jones said this treatment at the former North Wales Hospital, which has since closed, left him with no sex drive.

After the treatment, Mr Jones said he was "rewarded" by doctors with straight porn.

"There was not much dignity there, but I was encouraged to think this was a bona fide treatment and I should participate in it as well as I could," he said.

"The idea was that I would link the negative shock with the homosexual pornography and the freedom from shock with heterosexual pornography."

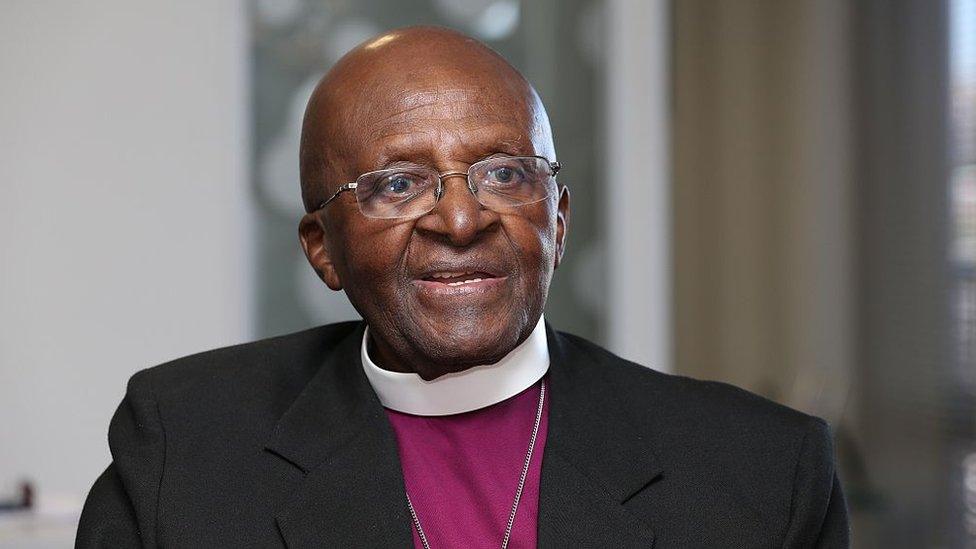

Mr Jones' recent prostate cancer diagnosis has made him think about how he has never been given an apology for what he suffered

He said he was given electric shock aversion therapy for one hour a day for several weeks, and was only released from hospital after he "tried to play along".

But after leaving he tried to kill himself because the treatment had failed, before being taken back to hospital.

'Gay-positive therapy'

There he said he was tranquilised and drugged rather than being given the shock therapy.

"For years, if I had any sense of sexual arousal I would have flashbacks of the therapy I received," he said.

For a decade, until he was 28, Mr Jones suffered symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and he said he was unable to have a healthy sexual relationship.

But going to California for university in 1984 helped him.

He said: "I put all of my energy into academic study and whilst there I had the opportunity to have therapy that was gay-positive, which allowed me to unlearn a lot of the negativity I had learned or absorbed as a child, and I was able to regain a sense of myself.

"The damage the aversion therapy did to me for around seven years completely destroyed my ability to have any kind of fulfilling relationship.

"Had it not been for the therapy in America, I don't know where I would have ended up."

Mr Jones, pictured with his husband Jupp Korsten, says he was able to regain a sense of himself through counselling in California

Now living in Germany with his husband Jupp Korsten, who's been his partner for 37 years, Mr Jones said it was important to ban the "dreadful" practice.

But he said he had doubts about being able to stop therapies aimed at "praying the gay away" as they are carried out "in private back rooms, often linked with religion and faith".

"How do you police quiet conversations which try and influence change in family homes and religious establishments? It would be a nightmare," he said.

Having recently being diagnosed with prostate cancer, Mr Jones said he had reflected on how he was never given an apology for what he was put through.

"An apology would be powerful for those that have lived with the psychological consequences of conversion therapy," he added.

Neither the NHS in England nor the NHS in Wales responded to a request to comment or offer an apology.

Mental health groups have warned all types of conversion therapy are "unethical and potentially harmful", external.

"My sexuality is not a sickness": A gay man and a lesbian's experiences of "gay conversion therapy" in Jordan

Alia Ramna, 22, a transgender woman from Cardiff, has also been put through conversion therapy.

She said: "I knew I was different and it was a gradual realisation, but it got to a breaking point when I was 16 and I couldn't conform anymore.

"I realised if I didn't come out I would die because I couldn't see myself as a man anymore.

"I saw no other option, it was either death or transition."

Alia Ramna went through conversion therapy in an effort to try and suppress her gender identity

Ms Ramna said when her family found out, they made her recite religious verses to "pray the gay away".

"For conversion therapy to still be happening in 2023 is awful - it is still happening in homes and behind closed doors," she said.

Ms Ramna said there needed to be safe spaces for trans and non-binary people and discreet ways for people to seek help.

Andrea Williams, chief executive of Christian Concern, said the ban would "end up criminalising consensual conversations with those who genuinely want help and support".

Christian Concern is preparing legal action against any proposed legislation in this area.

The Evangelical Alliance, which said it represented 3,500 churches, argued a ban could jeopardise religious freedoms., external

The Muslim Council of Wales said it had deep reservations, adding the ban could undermine religious freedoms.

A spokesman added: "To protect minorities from harmful and abusive treatment is a worthy goal, however legislation is a blunt tool and often produces unintended consequences."

The planned ban will outlaw attempts to change someone's sexuality or gender identity

However, the Church of England said the practice had "no place in the modern world".

The UK government said it would be publishing a draft bill to ban conversion practices.

A spokesperson added: "The police are experienced at dealing with crimes in private settings, and we will publish more details of how the ban will protect those at risk in due course."

If you have been affected by any of the issues in this story, the BBC Action Line has links to organisations which can offer support and advice.

- Published20 September 2024

- Published17 January 2023

- Published12 May 2022

- Published4 March 2021

- Published16 December 2020

- Published16 December 2020

- Published16 September 2019