Tryweryn: The stories behind drowned village Capel Celyn

- Published

Mr Jones Parry, the postmaster, outside his post office at Capel Celyn on 10 December 1956 which was submerged when the valley was flooded

Betsan Powys grew up with the story of how the Welsh-speaking village of Capel Celyn was drowned to provide drinking water for Liverpool.

From her decades-long career as a journalist she thought she knew the story. But making a podcast about the drowning and the protests that followed gave her an opportunity to look beyond the passion and the myth.

The drowning of Capel Celyn is an emotive topic in Wales - the passion some feel almost 60 years on should come as no surprise and has been well documented.

When speaking to people whose homes were bulldozed and flooded and hearing the stories of those directly involved in the decades of political protest that followed, what struck me most were the nuances and complexities that came to light.

It's by listening carefully to these that you get to see beyond the story I thought I knew.

In my podcast Drowned - The Flooding of a Village, I wanted to explore not just what happened but why it happened from many perspectives, and was keen that the story was told by those who had lived it.

My aim was to find facts not myths.

A couple at their home in Capel Celyn on 27 February 1957

In 1965 - the same year as I was born - the nine-year battle to save Capel Celyn was finally lost and the village was flooded.

Growing up, it was talked about at my school in Cardiff, but I would also have heard the story at home.

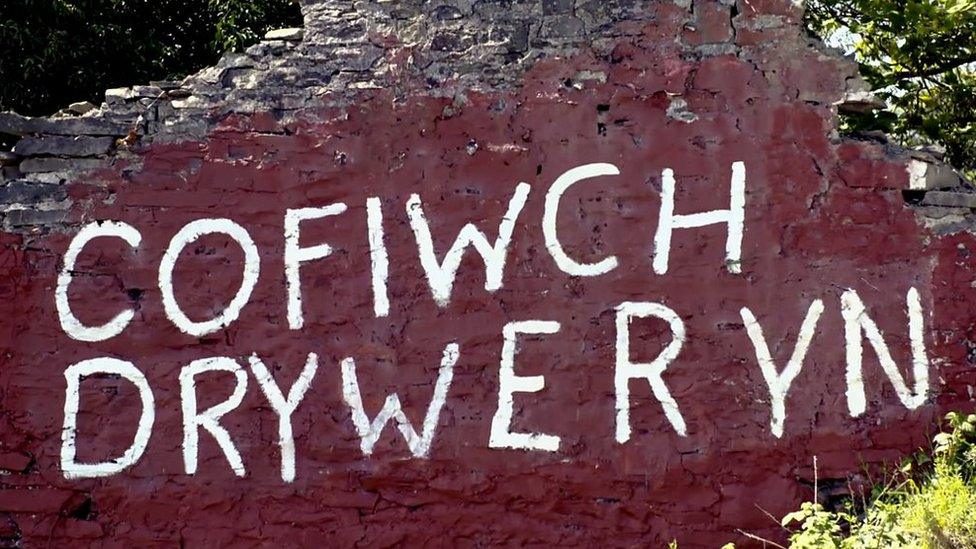

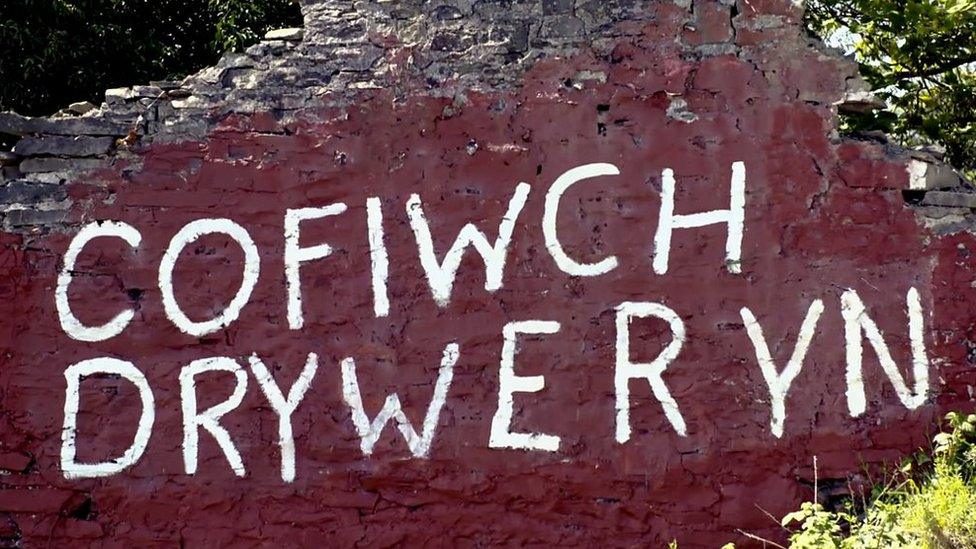

My mother grew up on a farm near the famous graffitied Cofiwch Dryweryn (Remember Tryweryn) wall near Llanrhystud, Ceredigion, and whenever we went to visit my grandparents, we would pass it.

The graffiti appeared in the 60s and the wall has become a bit of a Welsh landmark, iconic in itself, inspiring similar graffiti works across Wales.

Author Meic Stephens painted the Cofiwch Dryweryn mural on the wall of a ruined cottage in the early 1960s

Hoodies and other merchandise bearing the words are also worn by some in Wales as a symbol of national pride and defiance.

Growing up, the conversations around Tryweryn were emotionally charged - and the context of the story was clear, that a Welsh-speaking community had been destroyed at a time when the language was under threat, all protest swept aside by the authorities in Westminster and in Liverpool who would benefit from a new supply of water.

But it was more than that.

It was proof of Wales' political impotence, always out-voted and out-muscled by its more powerful neighbour.

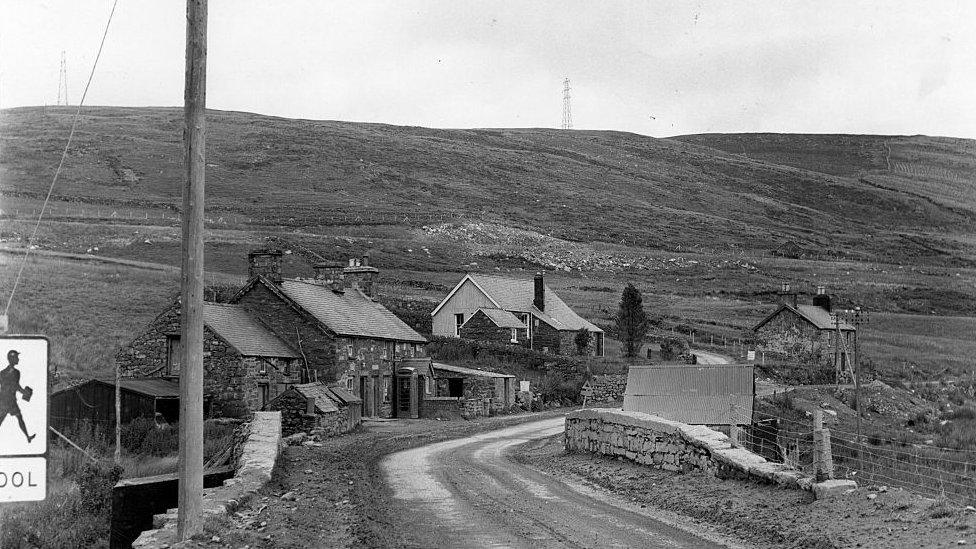

Capel Celyn in July 1963

What happened to Capel Celyn?

In the summer of 1955, the people of Capel Celyn learnt their homes had been earmarked as the site of a new reservoir to provide water for Liverpool.

This would mean destroying houses in the village near Bala, Gwynedd, and rehousing the villagers elsewhere.

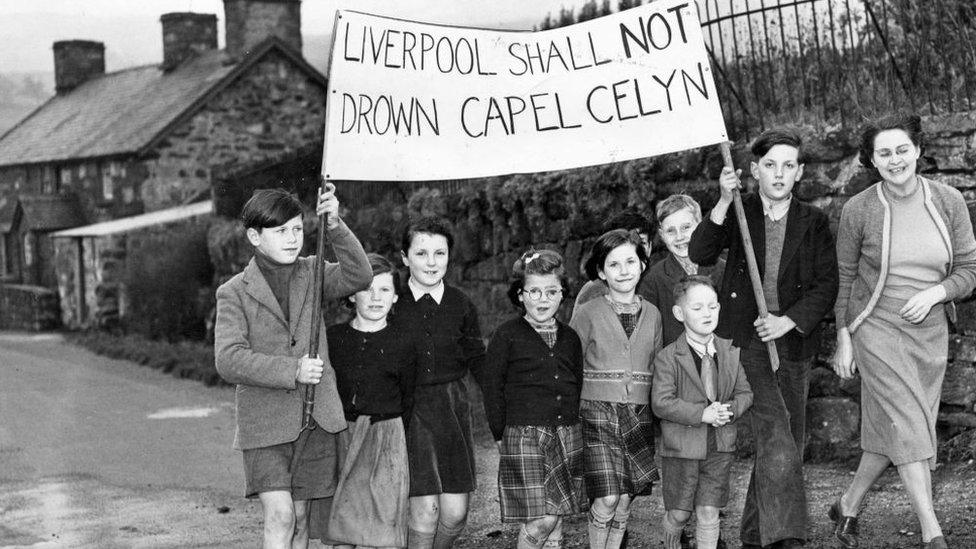

For almost a decade after the announcement, the villagers fought to save their homes, with protests and marches through the streets of Liverpool.

Schoolchildren from Capel Celyn protesting against the drowning on 18 December 1956

The village could not be saved and in 1965 Capel Celyn was flooded, with 75 people having to leave their homes.

Its 12 farms, school, chapel and post office disappeared under water.

Betsan visited the Liverpool Record Office as she researched the history

Liverpool's perspective

Visiting the Liverpool Record Office, it struck me that this is Liverpool's story too of course.

But it is a very different story.

Before Tryweryn, Liverpool was already getting its water from Wales - but the city's council argued there wasn't enough of it.

The demand for water in Liverpool had been growing, and as local politicians strove to clear poor housing and improve conditions, they saw a need for a bigger, better water supply.

Building the Tryweryn reservoir by drowning Capel Celyn was seen as serving a vital and greater good.

Thousands of families in Liverpool would benefit while the handful of people who lived in Capel Celyn would be rehoused.

I spoke to the songwriter and broadcaster Sir Richard Stilgoe, whose father, John Stilgoe, was Liverpool's chief water engineer.

He designed the Tryweryn reservoir, and Sir Richard remembers spending many Saturdays as a teenager visiting the site.

While there, he described seeing a mutual respect growing between his father and the people of the valley.

It's the fact that Liverpool is in England and Capel Celyn in Wales that turned an honourable attempt to serve "a greater good" into "perceived bullying," he believes.

Welsh nationalist demonstrators were confronted by police on 21 October 1965 at the opening of Tryweryn reservoir

Liverpool protest

I also spoke to the son of the village school's head teacher Martha Roberts.

Gwyn Roberts recalled his mother talking about travelling with other villagers on the bus to protest in Liverpool.

She was, he says, extremely proud of her professional status as a teacher and wasn't sure how she felt about being seen on the streets with a placard in her hands.

Yet, she wanted to support her pupils and their families and so joined the protest.

Elwyn Edwards was a schoolboy who lived nearby and truanted so that he could join the protest.

He shared his parents' fury at the plans to flood Capel Celyn and wanted to do something to support the village.

Back in class the next day, his headmaster was equally furious that he'd missed a day's school.

The tiny village of Capel Celyn wasn't, in his view, worth it.

And an honest telling of the story reminds us that not everyone in the area saw injustice.

Some saw jobs and opportunity.

Dr Wyn Thomas has written a book - Tryweryn: A New Dawn?

Martha and Elwyn's stories are just two that go to the heart of the little complexities that are sometimes drowned out by big headlines.

Author and historian Dr Wyn Thomas has delved deep into the history of Tryweryn and has meticulously unravelled the story behind it.

He sees beyond the emotion and yet, as I learned, is deeply touched by it.

His father was a police officer at a time when a Welsh paramilitary group was responsible for blowing up pipelines carrying water to England.

He had to go out late at night with his flashlight to check the water pipes in case explosives had been attached.

Wyn saw his mum worry about his dad being placed in danger.

To this day, his interest in documenting an event that many see as a turning point in Welsh history is influenced by that experience.

It's the effect history has on ordinary people that matters to him.

'We mustn't mythologise'

I also met Emyr Llywelyn, one of three men who bombed the site of the planned reservoir in a bid to save the village.

He too is aware that as time goes by, it's all too easy for myth to take over from fact.

"We mustn't mythologise, we must tell the story as it was," he told me.

Aeron Prysor Jones with his grandson Gwern

As a child Aeron Prysor Jones was moved out of Capel Celyn for it to be flooded.

He lived in a caravan through the freezing cold winter that followed while work was carried out on the farmhouse where he and his family live to this day.

It sits above the Tryweryn waterline with a view out over the water.

Gwern and the roof tile he found at Tryweryn during the drought

His young grandson Gwern visited the reservoir during the drought last year and found a roof tile from one of the demolished buildings.

He took it home to show his grandfather, proud of this reminder of his family's story.

Aeron firmly believes that Wales wouldn't have its own national government or a Senedd now in Cardiff Bay, had Capel Celyn not been drowned.

"It was the spark," he says. "The village name should be there in huge letters for all to see."

The challenge for Gwern and his generation is not just to know their own history, but to make their own decisions about what comes next for Wales.

Drowned - The Flooding of a Village is available on BBC Sounds

COFIWCH DRYWERYN: A new podcast explores a dark and controversial chapter in Welsh history

HEART VALLEY: A day in the life of a curious Welsh shepherd

- Published2 September 2022

- Published10 February 2023

- Published10 February 2023