Cancer: As a black man I wasn't included in cancer stats

- Published

Four years on from his diagnosis, Spike says he's thriving rather than simply surviving.

What started as a shoulder ache led to a whirlwind diagnosis of stage four cancer and a rare genetic mutation for Spike Elliott.

But his journey also highlighted a worrying ethnicity data gap in our health system.

It comes as research by one charity shows just how few patient records include ethnicity information in Wales.

The Welsh government said it was working to improve the diversity of data collection and health research.

One oncologist said it meant assumptions were made about how patients will respond, despite there being "clear differences" in how certain cancers affect different racial groups.

"It made me feel isolated, as though I wasn't included in the cancer world," said Spike, whose parents are both Jamaican.

"I was given a life expectancy of six to 12 months. That was statistically supported.

"But I was alarmed when I was made aware that the statistics don't include the BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) community.

"Because what was my outcome then?"

Judi Rhys from cancer charity Tenovus said patient ethnicity data was not routinely gathered, despite a mandate to do so.

She has written to the health minister calling for more to be done.

"We know in terms of cancer, right throughout the journey that ethnicity is an issue and often people from black and minority ethnic groups have poorer outcomes," she said.

"We know that health boards are not collecting that data routinely - the figures vary between the health boards from 15% to 55%.

"We are clearly a long way behind, with lot of work to do in Wales."

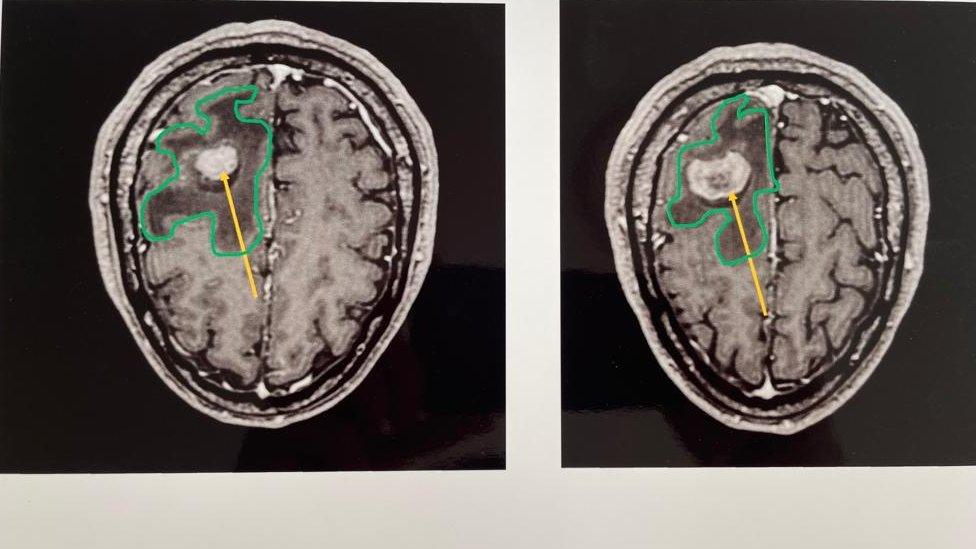

Spike's brain scan (left) show a his tumour smaller after treatment, compared to the larger tumour on the right

She added that a new IT system used in cancer informatics does not have the option to detail a patient's ethnicity.

Emmanuel Ogbonna is professor in management at Cardiff University Business School.

"The vast majority of people don't intend to discriminate in any way, shape or form," he said.

"But because in their everyday lives they support a system that is already racialised, the only outcome you can get from that system is a racialised outcome."

As co-chairperson of a group that helped produce the Welsh government's anti-racist Wales action plan, external he knows work is under way to address disparities, but said trust was a factor.

Dr Jason Lester knew that the ALK gene mutation was incredibly rare, particularly among black men, but felt the genetic testing was worth pursuing for Spike

"Many people from minority ethnic communities will tell you that they have data coming out of their ears and out of the ears of the authorities, but nothing gets done to benefit them.

"So we have to create that degree of trust, so that people feel and know that if you are asking them for health information that you are going to use it for something that is going to benefit them and not something that disadvantages them."

Spike was a fit, active 49-year-old father-of-two when he first felt an ache in his shoulder in 2018.

A scan detected "abnormalities" but he was shocked to be told immediately after the scan to go straight to A&E for further tests.

After five days of tests and blood screenings, the interior architect from Cardiff was formally diagnosed with stage four cancer.

"I said 'I think you've got the wrong person'."

While the cancer had started in his lung, it had spread to his brain, causing the ache in his shoulder.

Prof Emmanuel Ogbonna said gathering data was not enough without change coming as a result

The initial plan was surgery to try and access the tumour, but during a meeting between specialists, consultant clinical oncologist Dr Jason Lester recognised that non-smoking Spike might actually have a rare gene mutation called ALK, external.

It meant Dr Lester "was very hopeful" that a tablet would be more beneficial to Spike, rather than surgery to try and remove as much of the tumour as possible.

He said ALK mutations were very uncommon in lung cancer, with higher frequency among Asian people, compared to "very low incidence" in white people.

"In black patients there's very little published data on it," Dr Lester said.

"But the evidence suggests it's even less common in black patients than it is in white patients, so it could easily be missed."

While Spike waited for the results of the genetic test, his symptoms worsened as the cancer spread to his spine, kidneys and lymph nodes, as well as gaining weight due to the steroids he had to take.

"My right side was becoming limp, especially my legs," he said.

My arm started to claw and I couldn't walk any distance and I was constantly breathless.

"I just tried to keep my sanity by focusing on my breathing.

"I was in pieces and just trying to bring myself together again."

Once the ALK gene mutation was identified he was put on a drug called Alectinib.

"Within days I felt different," he said.

After several months the brain tumour had more than halved and all other organs were clear of cancer.

Spike said: "I'm now beginning to thrive. Which is a huge step from surviving."

His health has now improved to the extent that he has returned to playing his beloved sport football and coach his son's under-11s team.

Spike has been able to return to the things he loves, including coaching his son's under 11s football club

As a mixed race man himself, Dr Lester supports the call for better ethnicity data.

"What's always struck me about the research that is published out there on cancers is that there's very little actually on black people," he said.

"If you look at the big studies that have been done on treating patients with lung cancer - the vast majority of the patients are either white or Asian.

"Black people make a very small proportion of those clinical trials.

"So you're almost having to second guess, in some ways, the sorts of cancers that you might see and how those individuals might respond to treatment if they are black because the data out there is very poor.

"It's all guesswork, but it shouldn't be."

The Welsh government said: "We are working with partners to identify barriers and find solutions to improve data collected at point of contact, including through our race disparity evidence unit, external, so more data is captured and available on ethnicity.

"Clearer guidance and expectations are also being developed around how diversity needs to be considered in the design and delivery of health research studies. This will influence treatments offered."

- Published24 January 2023

- Published15 June 2019

- Published7 June 2022