Organ donation: Powys dad in limbo as he waits for heart

- Published

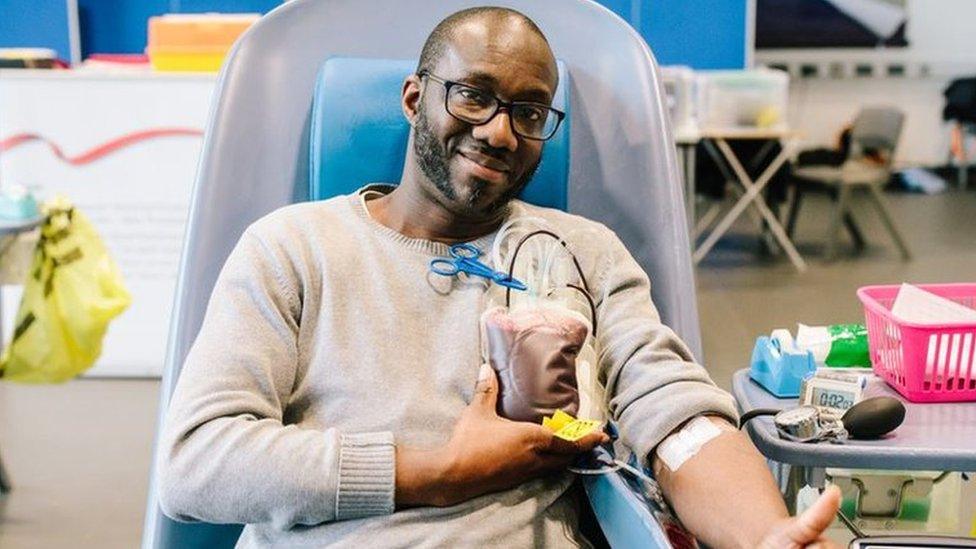

Kal Sandhu has been waiting for a new heart for three years

A dad-of-two who has been waiting for a heart transplant for more than three years has said he feels "in limbo".

Kal Sandhu, 51, from Brecon, Powys, was born with a congenital heart condition.

He is one of several from an Asian background who, alongside other diverse racial backgrounds, face longer average transplant waits than white people.

The lead nurse for organ donation in south Wales said this was often due to low consent rates and families not knowing loved ones' wishes.

Mr Sandhu, a lawyer, has never known what it is like to have a fully functioning heart and has been waiting for a call to tell him there is a heart for him since 2020.

He has had open heart surgery twice, as well as several other heart procedures, and has to travel to University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff every three weeks for transfusions to keep him alive.

"I'm waiting for a new heart that's had one careful owner," he said.

He said this has left him in "limbo" with "no control" and said the impact on his family was hard.

"When you see the fear in their eyes… that's when the wait really starts to get to you."

Patients from black, Asian and ethnic minority backgrounds accounted for 22% of those who died waiting for a transplant in the UK in 2022-23.

According to 2021 Census data, 18% of the population of England and Wales belong to one of those groups.

Mr Sandhu has had open heart surgery twice as well as several other heart procedures

Mr Sandhu's wife, Ros, a mental health worker said it had been "really tough" seeing him deteriorate from "leading a full and normal life" to needing to use a wheelchair.

She said: "As humans, we avoid the subject of death. That would include discussions about organ donation."

She added their situation had taught her it was important to discuss organ donation with family members, but also what kind of funeral and how they want to be remembered.

"I know it sounds morbid, but it's actually weirdly life-enhancing," she said.

Mr Sandhu said organ donation was "incredibly brave" and "selfless" and wanted to encourage families, especially those from different ethnic backgrounds to discuss their wishes with loved ones.

"Without sounding too dramatic, I want to be there for my when my daughters graduate. That would be my best outcome."

In 2015, Wales introduced deemed consent for organ donation - meaning people are automatically considered to have no objection to becoming a donor unless they say otherwise.

But experts say a lack of discussion mean some families are choosing to withdraw consent when their loved one has died, due to uncertainty, cultural or religious beliefs.

It has lead to consent rates from ethnic minority backgrounds being less than half of the white population, according to Charlotte Goodwin, the lead nurse for organ donation in south Wales.

She said not discussing wishes left family members "wondering what's the right thing to do".

Discussions around donation among black, Asian and people from other ethnic minority backgrounds could lead to shorter waiting times for these groups as "heritage" and "ethnic characteristics" can lead to a better organ match, Ms Goodwin said.

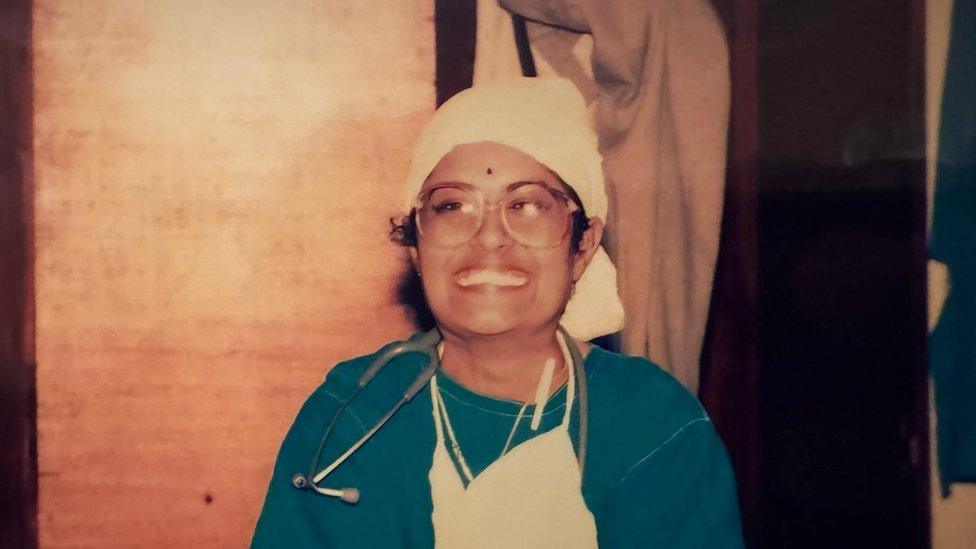

Poornima Sreekumar's family chose to donate her organs when she died suddenly

Sandhya Sreekumar's mother, Poornima, died suddenly when she was 56.

Poornima was a doctor when she suddenly collapsed at work, having experienced a cerebral haemorrhage caused by an unknown brain aneurism.

The anaesthetist from Newport never regained consciousness and died a week later.

It was "a huge shock" for the family, said Ms Sreekumar, 31.

Her dad, who was also a doctor, decided to donate Poornima's internal organs, despite not knowing her exact wishes.

Ms Sreekumar said: "Mum and dad had both worked at some point or another with organ transplant, so I think it was it was pretty important to her."

Sandhya Sreekumar says she has been very vocal with family about donating her organs

Poornima was a devout Hindu Brahmin and although Ms Sreekumar said "there's a lot of variation about what Hinduism might say about organ donation", she believes it "falls within the ethics of faith".

As a result of her mother's sudden death, she has been "very vocal" with her loved ones about her wishes to donate her organs.

She thinks it is an "excellent thing to do", to "help other people after you're gone" and wants more people to speak about donation even though "death is taboo".

"We had to guess her [mum's] wishes after she was gone. It would have given us more peace of mind if we'd known from her directly.

"She worked very hard to become a doctor in the first place and she was very proud of being one.

"I think that being able to continue, essentially, in some ways, being a physician after death is probably a good legacy to have."

A POSITIVE LIFE: HIV from Terrence Higgins to today

ACID DREAM: The Welsh farmhouse that sparked a revolution of the mind

- Published5 April 2023

- Published26 April 2023

- Published12 January 2023