Anthony Hopkins in One Life prompts Llanwrtyd Wells memories

- Published

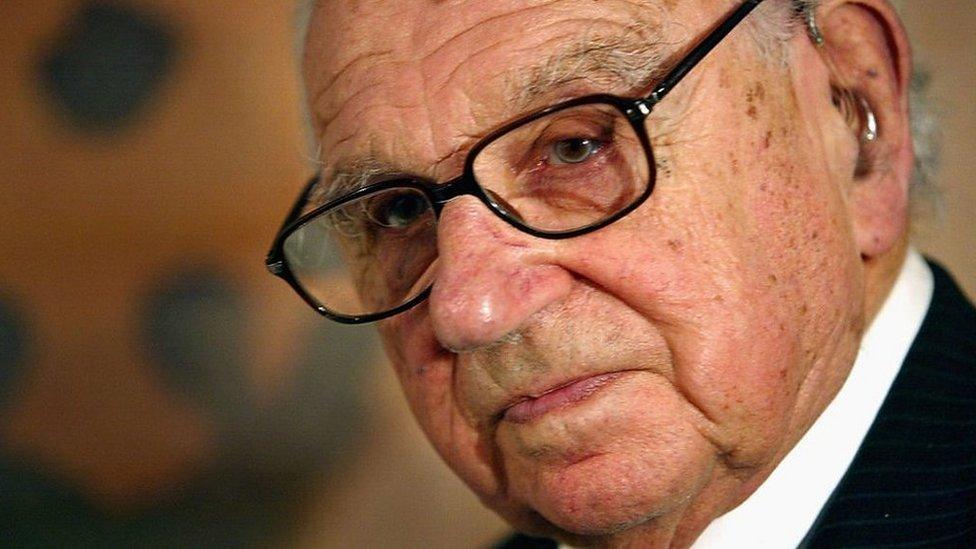

Sir Anthony Hopkins portrays Sir Nicholas Winton in his later years

More than 80 years have passed since six-year-old Alfred's desperate mother put him on a train in a bid to escape the Nazis, unsure if she would ever see him again.

Lord Alfred Dubs, now 91, was one of 669 mainly Jewish children who escaped Czechoslovakia without their parents on a Kindertransport train, which rescued some 10,000 children from territories occupied by Nazis.

The now-veteran Labour peer and about 140 of the child refugees from Czechoslovakia were then schooled in Llanwrtyd Wells, Powys, where the welcome they received "ought to be a lesson for all of us today," he said.

The story of how British stockbroker Nicholas Winton facilitated the rescue of hundreds of central European children from the Nazis on the eve of World War Two has been told in Sir Anthony Hopkins' new film One Life.

Watching it left Lord Dubs with tears pouring down his face.

"It was a bit like lying on a psychiatrist's couch and revealing oneself," he said.

"None of us who went through the Kindertransport experience and who saw the film will ever be quite the same again having seen the film."

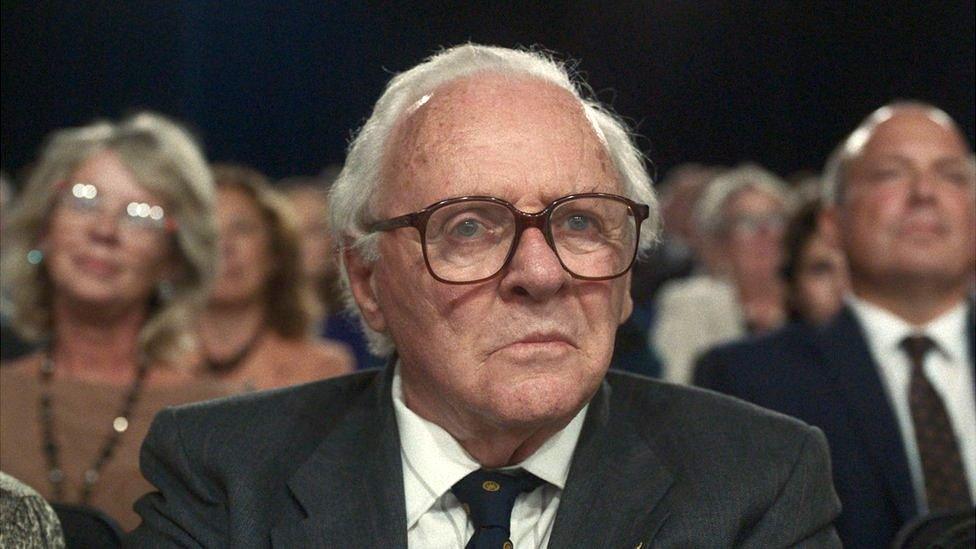

Lord Dubs (left) and Sir Nicholas Winton were friends until the latter's death in 2015

Six million Jewish people died in the Holocaust - the Nazi campaign to eradicate Europe's Jewish population - and Auschwitz was at the centre of that genocide.

The role Sir Nicholas Winton played in organising the rescue was widely unknown until almost 50 years later when he was reunited with dozens of the children he helped on the BBC's That's Life programme.

Following the programme, the British press celebrated him, dubbing him the "British Schindler" and he was knighted for services to humanity in 2003.

He also became a friend to Lord Dubs and many of the other children he saved.

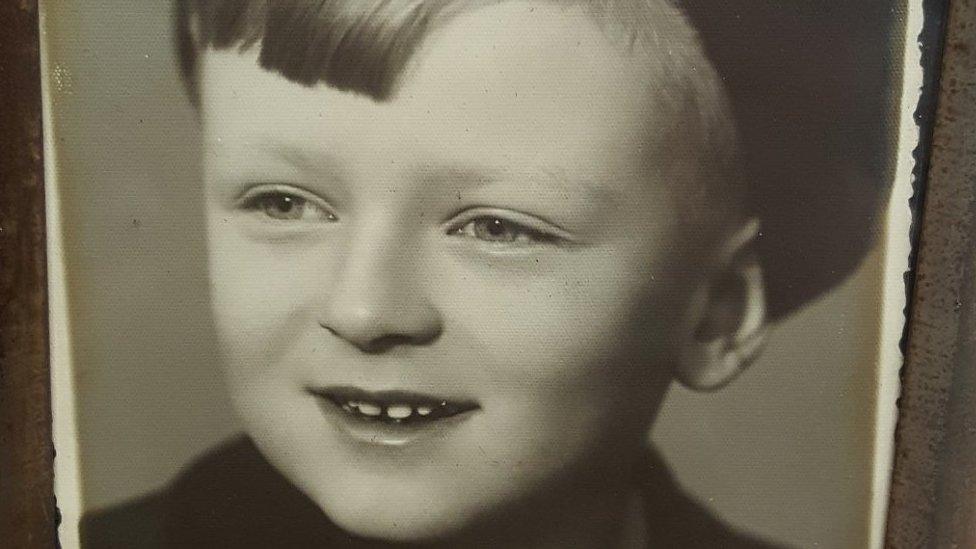

In June 1939, young Alfred's mother had no choice but to put her only child on the London-bound train at Prague's main station.

"I can still see her in my mind's eye at the station with lots of anxious parents," said Lord Dubs.

"It was quite an emotional moment... I was quite bewildered... there was no knowing whether we'd see our parents again.

Six-year-old Alfred Dubs left Prague on a Kindertransport train in 1939

As a six-year-old he wasn't entirely sure of what was going on.

"When the train reached the Dutch border the older children cheered because were out of reach of the Nazis," he said. "I knew it seemed significant, but I didn't know why."

His father, who was Jewish, had already fled Prague and was able to meet him at Liverpool Street station in London.

Shortly after his arrival in London his mother was also able to escape and the family were reunited.

Unable to speak English, they moved to Northern Ireland where his father had found a job.

Within a year his father had a heart attack and died at the age of 45, leaving he and his mother in a state of shock and grief and with no income or home.

They stayed with friends in Manchester and Alfred attended a primary school in Cheshire.

In 1943 he was sent to board at Czechoslovak State School, which had been established by the Czechoslovakian government-in-exile in Wales' smallest town, Llanwrtyd Wells.

The former Czechoslovak Secondary School was home to about 140 child refugees

The school had initially been located in Camberley, Surrey, and then evacuated to Hinton Hall in Shropshire before relocating again to the Abernant Lake Hotel in the Welsh market town.

The school was home to about 140 pupils, mostly from Jewish backgrounds.

"Thank you Llanwrtyd Wells, I have such warm memories, what a lovely place, what lovely people," said Lord Dubs.

"There we were, a bunch of young people from a distant country arriving in a little Welsh town and we had such a welcome.

"That ought to be a lesson for all of us today... I would like to feel we can go on doing that to people who come as strangers who've been through the most terrible experiences."

He said often it was small things that made them feel welcome.

"When we went into a shop they immediately switched to talking English [from Welsh], which was a real courtesy. They were ever so friendly."

Of course, the children at the school were all refugees who had all been through the ordeal of being forced to leave their homes and families and many faced an uncertain future.

"I was beset by anxiety because my mum was sleeping on the sofa of some friends in Manchester and I had this terrible sense that I had no home," he said.

Many of the other children had parents still in Czechoslovakia and did not know their fate.

"In one sense I had a parent and some of the other children didn't see their parents again or only saw them many years later," he said.

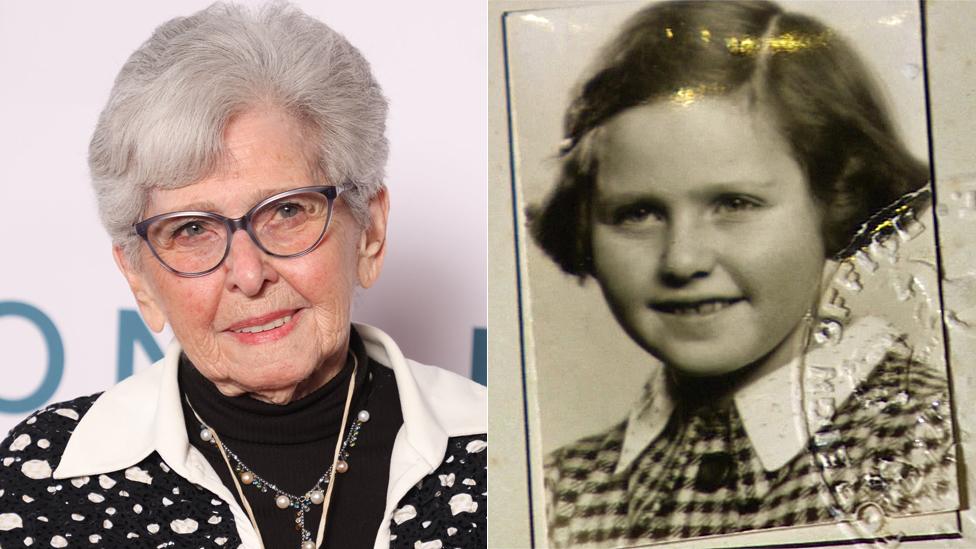

Lord Dubs, here with actress Vanessa Redgrave, has been a lifelong campaigner for refugees

Lord Dubs has visited the town several times over the years for reunions and "once just sentimentally with my wife".

"We just stayed at the Abernant Lake Hotel and it was just an emotional thing," he said.

Lord Dubs's mother died when he was 25.

After studying at the London School of Economics he entered a long career in public service.

Before being appointed a Labour working peer in 1994, Lord Dubs was the Labour MP for Battersea South between 1979 and 1987.

Sir Nicholas Winton received the Order of White Lion, the highest order of the Czech Republic, in 2014

It was not until 1988 that he first heard the incredible story of the man who had organised the rescue of himself and hundreds of other children from Czechoslovakia.

"I knew nothing about Nicholas Winton until it all came out on television and then the whole story unfolded," he said.

"I was delighted to get to know him and, in a way, we became good friends."

They would meet up for lunches and celebrations until Sir Nicholas died in 2015, aged 106.

"A lot of us felt we owed our lives to him and it's quite something to meet a very unassuming, modest man and feel that, were not for him, we wouldn't have survived the Holocaust.

"Obviously there are very complicated feelings, strong emotions in all this."

Lord Dubs says seeing the film was an emotional experience

He said it had been a privilege to get to know such a remarkable man who had a sharp wit and was passionate about politics and believes we can all learn from Sir Nicholas.

"In life lots of us see a problem and say 'how awful' and we walk away, but he didn't walk away.

"He saw the problem and said 'I've got do something about it' and together with friends he did it."

A statue of Sir Nicholas Winton and two children is at Prague Central Station

Seeing One Life had a big impact on Lord Dubs.

"I sat there and the tears poured down my face and I just couldn't control it," he said. "It made me wish [my parents] had lived long enough to see me in life and to see what happened."

He was taken aback by Sir Anthony's portrayal of his friend.

"Anthony Hopkins was absolutely like Nicky Winton," he said.

"I found it uncanny that it wasn't Nicky. I thought, 'Nicky's dead. How can he be in this film?' It was such a good portrayal."

Lord Dubs said he believed it was important to keep talking about atrocities of the past.

"I don't think we should ever allow the Holocaust to be forgotten," he said. "We've got to learn the lessons of what happened... and keep reminding ourselves of these terrible things the world went through.

"Nicky Winton would certainly have wanted it."

- Published4 January 2024

- Published5 January 2024