How did the 1980s miners' strike affect Wales?

- Published

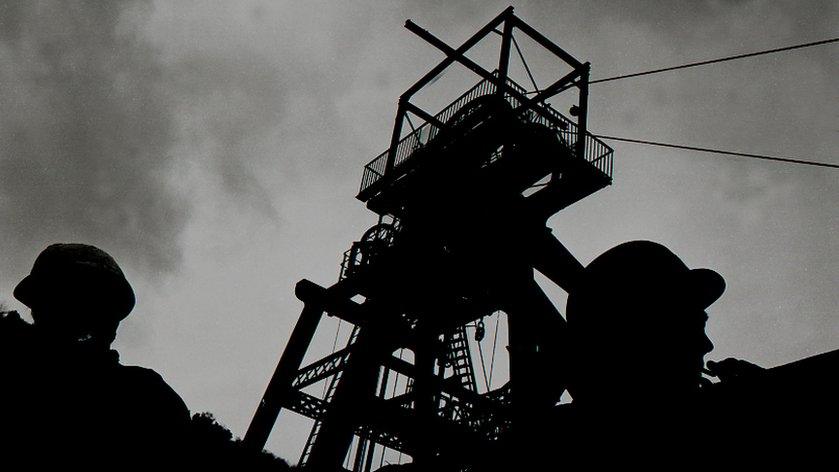

The miners' strike was the longest and most acrimonious industrial dispute in modern British history

When miners at Cortonwood colliery in Yorkshire downed tools on 5 March 1984, they helped set off a chain of events that was to reshape the industrial and political landscape of Britain forever.

The miners' strike of 1984 to 85 saw the 22,000 miners of Wales plunged into conflict with the Conservative government.

It was a year-long fight to retain jobs and keep pits open in areas - particularly the south Wales valleys - where little other employment existed.

Why was mining so important to Wales?

At the start of the industrial revolution in the late 18th Century, the valleys of Wales were sparsely populated.

But the large scale exploitation of iron ore lying side by side with vast coal deposits - the largest continuous coalfield in Britain - was to transform the landscape, both physically and socially.

The valleys towns grew up from largely unpopulated rural countryside

Ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil and Blaenavon were fuelled by coal, and as the need for fuel and iron across the growing British Empire rose throughout the 19th Century, Welsh coal was more and more in demand.

Coal production soared, and workers poured in to the expanding mines. By 1900, south Wales was producing one third of global coal exports.

From a population of hundreds, the headcount in the south Wales mining valleys had mushroomed. By 1921, 250,000 men were employed in the pits, with thousands more working in related industries or providing services to the mining communities.

In north Wales, although a much smaller scale, there were 60 pits at the height of demand in 1918, each employing between 200 to 1,000 miners.

What was the state of the Welsh mining industry in 1984?

The glory days of coal mining were firmly in the past but it remained the biggest employer in Wales, with communities still revolving around the pits at their heart.

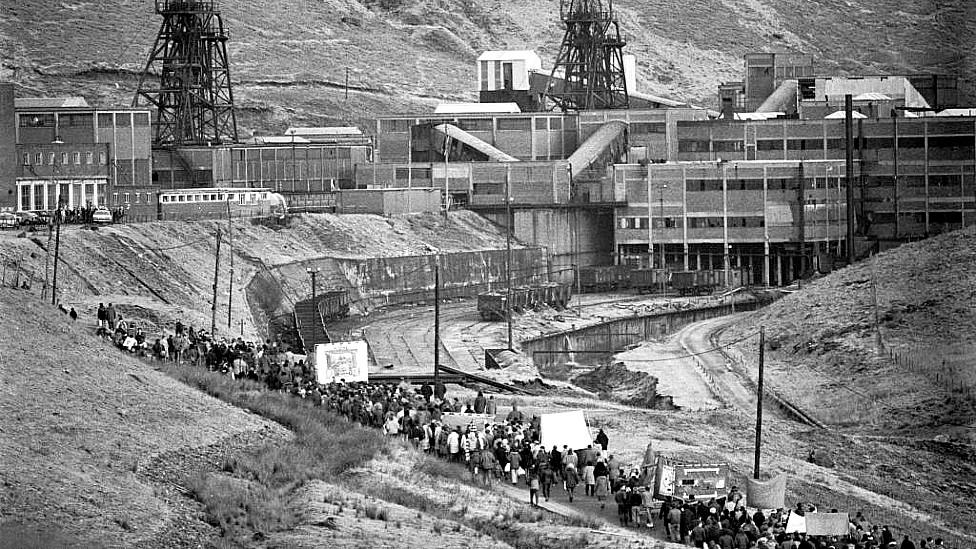

Mardy colliery was one of the most militant during the strike

The industry had been nationalised in 1947 under the National Coal Board, but pits struggled to compete with cheaper fuel, often from abroad, and many had closed.

Large-scale strikes organised by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in 1972 and 1974 when the lights went out and a three-day working week was imposed to preserve power -brought down the Conservative government led by Edward Heath.

The election of Margaret Thatcher as Conservative prime minister in 1979 brought two fundamentally opposed sides into conflict.

Mrs Thatcher wanted to privatise industry and break the power of the unions, particularly the NUM under the leadership of firebrand Arthur Scargill.

How did the strike begin?

The prime minister had prepared for this carefully. Coal had been stockpiled at power stations and new laws had restricted trade union activities.

The man who had been brought in to restructure the steel industry, Scottish-American Ian McGregor, was moved to the National Coal Board to achieve the same purpose in mining.

Mass closures of uneconomic pits were announced, possibly with the intention of forcing the miners into action.

Although a majority of miners in Wales had voted against striking, action by more militant workers to picket mines saw almost 100% solidarity with the strike across south Wales.

How did communities manage during the strike?

With the majority of miners not working, feeding and supporting mining families became a real issue.

Women were central to keeping communities going, but also got involved in campaigning and picketing

Women in the community organised food collections and distribution and fundraised, forging links with other groups and drawing in support from far afield in some cases, with food and money sent from places like France and Germany.

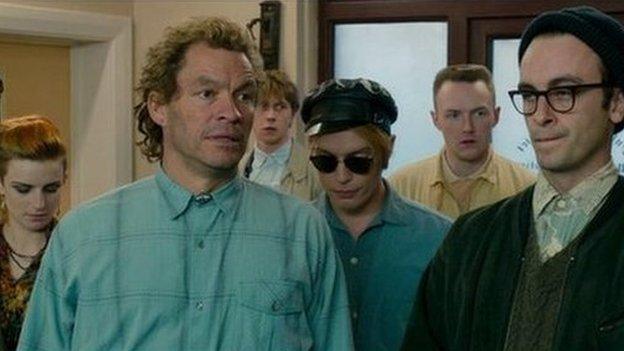

Alliances were forged in previously unlikely places, as depicted in the film Pride, which shows support for miners in the Dulais valley, Neath Porth Talbot, coming from gay and lesbian campaigning groups in London.

Things got tougher for communities as the strike wore on and the government froze NUM bank accounts and food funds, while benefits were cut.

Did all miners support the strike?

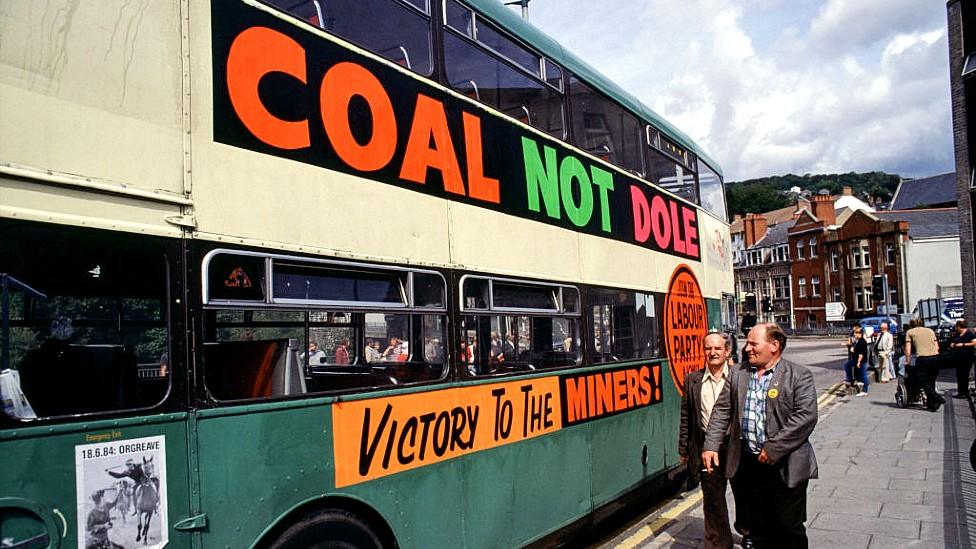

The Coal not Dole slogan summed up the reason miners were striking - many never worked again after the pits closed

Tensions ran high in north Wales, where support for the strike was much lower, leading to divisions between those out on strike and those continuing to work in different pits.

But even in south Wales, which saw the most solid action in Britain, as the months mounted, a small minority of miners - branded "scabs" - did return to work, causing bitter rifts within families and communities that in some cases never healed.

A couple of Welsh miners acting as "flying pickets" - protesters at mines other than where they worked or other sites such as power stations who tried to deter workers from crossing picket lines - were killed during the course of the strike.

And in November 1984, a taxi driver ferrying a strike-breaker to work was killed when a concrete block dropped from an overpass crashed through his windscreen.

How did it end?

The miners of Mardy colliery in Maerdy, Rhondda, marched back to the pit a year after the strike began

As the strike approached a year, the NUM recognised what had become the inevitable - that with nearly 50% of miners across Britain back in work, they were not going to win.

Delegates voted to end the strike, and on 5 March 1985 the miners marched back to work, most famously at Mardy colliery in Rhondda, south Wales.

In south Wales, only 6% of the workforce had broken the strike and it was the only area of the country to return to work fully under the instruction of the NUM.

The outcome, however, was the same everywhere. Within nine months, nine pits closed in south Wales and in 18 months the workforce was cut in half.

The last round of pit closures came in 1992, with only Tower Colliery in the Cynon Valley remaining open following a workers' buyout in 1994. It closed in 2008.

However in 1996 Aberpergwm mine in Neath Port Talbot reopened under private ownership and is still operational, producing anthracite coal mostly used by the steel industry including Tata steelworks in Port Talbot.

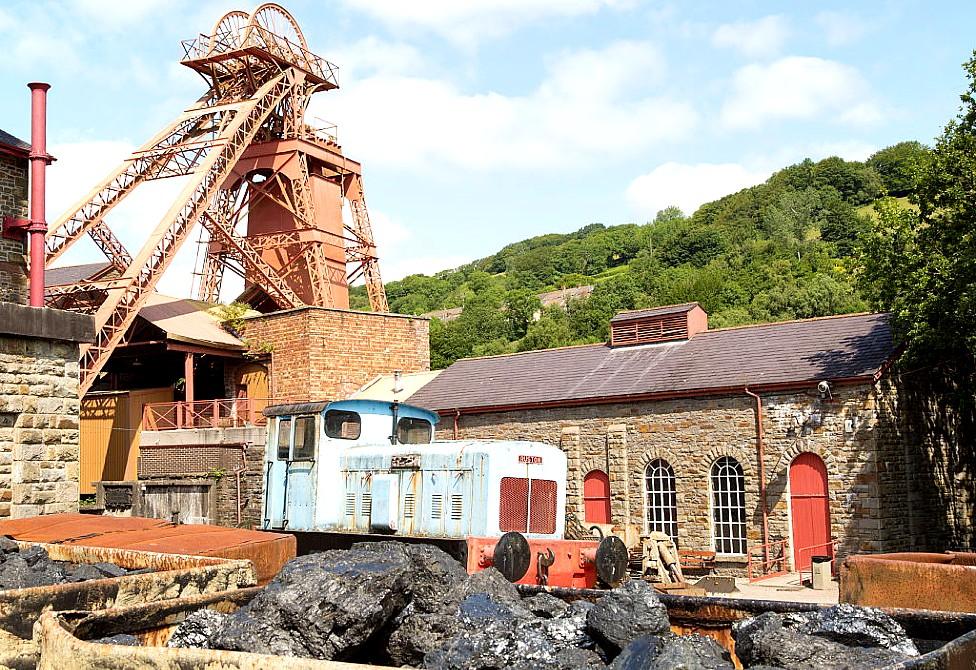

The former Lewis Merthyr colliery in Trehafod, Rhondda, is now a mining museum

- Published2 September 2014

- Published4 January 2020

- Published13 March 2014

- Published21 December 2015