Wales shares medical education with Namibian doctors

- Published

A team from Wales has just returned from an expedition to train young Namibian doctors in anaesthesia and critical care.

Prof Judith Hall, from Cardiff University, who led the expedition, explains why sharing education with the country on Africa's south west coast is so necessary.

I have travelled in Namibia, I know Namibia now, so let me paint you a picture.

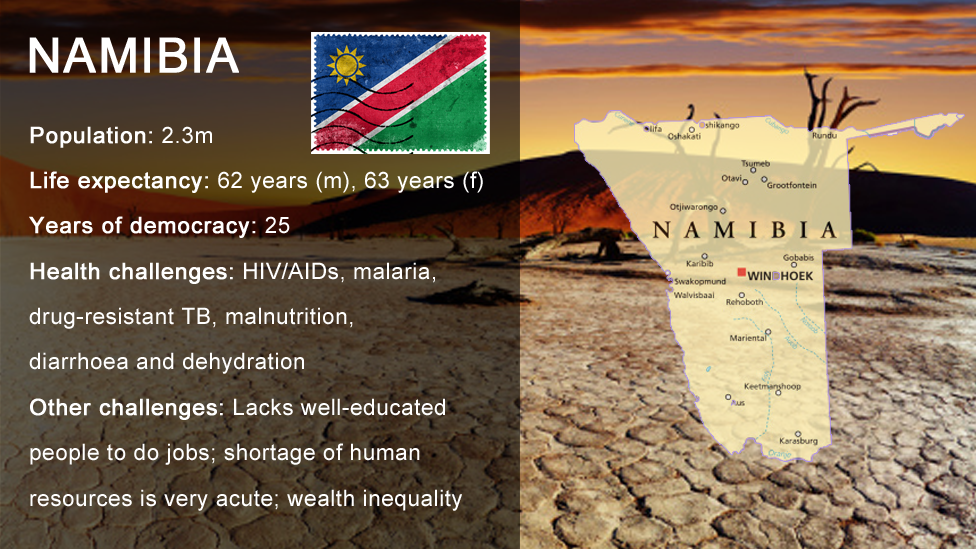

Namibia, a geographically huge country, has fewer than a handful of anaesthetists working in its NHS to serve 2.3 million people, while we have 160 anaesthetists for Cardiff alone.

If Namibia was to have a similar proportion of anaesthetists to Wales - with our population of three million - it would have more than 1,000.

This matters hugely because having no specialist anaesthetists means operations are cancelled and people die before they get treatment.

In fact, women are 17 times more likely to die in childbirth in Namibia than Wales, often because there is nobody to give anaesthesia.

Many of those who do give it are actually young doctors who have received just three months' training in anaesthesia, while our Welsh doctors train for eight years.

Mums die, babies die - I know because I've seen it happen throughout Africa where people have to travel enormous distances to get to a hospital for help.

There really is only one way that we can help, and that is through education: helping people to help themselves. In doing this, we in Wales learn different ways of working, thinking, coping and solving problems - both Wales and Namibia benefit.

Cardiff University's Phoenix Project, which I lead, was formed in response to the Welsh government's Wales for Africa programme, which works to eliminate poverty in Africa by 2030 in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

The idea of Phoenix is that shared education can address some of the challenges Namibia faces, not just in anaesthesia but in other areas such as midwifery, e-technology, teaching practices and maths.

Maths may sound a strange choice but you cannot have a water engineer unless he or she can do the sums.

So I am just back from Namibia with a dedicated team that has been working hand in hand with our collaborators, the University of Namibia, to make an impact on health promotion and poverty reduction.

Anaesthesia education is one of our most advanced projects and it is starting to have a major impact.

During 2015 the Phoenix Project, with support from the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland and global health body the Tropical Healthcare and Education Trust, has run three very successful anaesthesia courses.

We started in the relatively affluent capital Windhoek, but after that we took the project to remote, challenging, semi-desert areas in the north near the Angolan border, Rundu and now Oshakati.

We realised that Namibian doctors often worked in challenging conditions without the benefit of the state-of-the-art facilities that we enjoy here in Wales.

However we always found the same thing: a tremendous thirst for knowledge in local clinicians and really great support from the senior hospital staff.

The recent trip saw the majority of our six-strong anaesthesia team based at Oshakati hospital for two weeks where they trained 23 doctors from around the country and taught University of Namibia medical students.

Dr Josphina Augustinus, who runs Oshakati hospital, admitted she was sceptical about the Phoenix Project initially but now described it as "wonderful and meaningful".

"This has a great impact on the institution itself, Intermediate Hospital Oshakati, and also to the community because since people are well-acquainted with anaesthesia and well-trained, they will save lives," she said.

That is a great spontaneous endorsement from a very senior Namibian who wants more of what we have to offer, to make things better for her patients.

Dr Daylight Manyere, a senior doctor in a district hospital an hour south of Windhoek, explained some of the problems that the Namibian health service faces, particularly when there are so few anaesthetists.

"Most district hospitals don't have specialist anaesthetists so the anaesthesia is given by medical officers who went through the training during internship. If it's not your speciality you will always meet challenges and you want someone with expertise to help you so it's a big challenge across Namibia," she said.

"Other hospitals are not doing surgery because of a lack of trained anaesthetists. We consider ourselves lucky here because we have a functioning theatre and give safe anaesthesia."

One doctor, who has now attended all three of our courses, made a 20-hour round trip to attend the training in Oshakati.

He says he takes the information back and shares it with the junior doctors, so it is passed on to colleagues who also put it into practice. That is so rewarding to hear.

Next year will bring courses on airway management and, perhaps most significantly, a new Masters course in anaesthesia with the University of Namibia, the first the country has ever had.

This Masters will create a new body of professional anaesthetics doctors in Namibia, in sufficient numbers to truly transform care.

So let us see how far we can take this and impact on people's lives. These are exciting times - for Namibia and also for Wales.

- Published24 October 2015

- Published1 February 2015

- Published25 October 2012