Aberfan disaster survivors speak publicly 50 years on

- Published

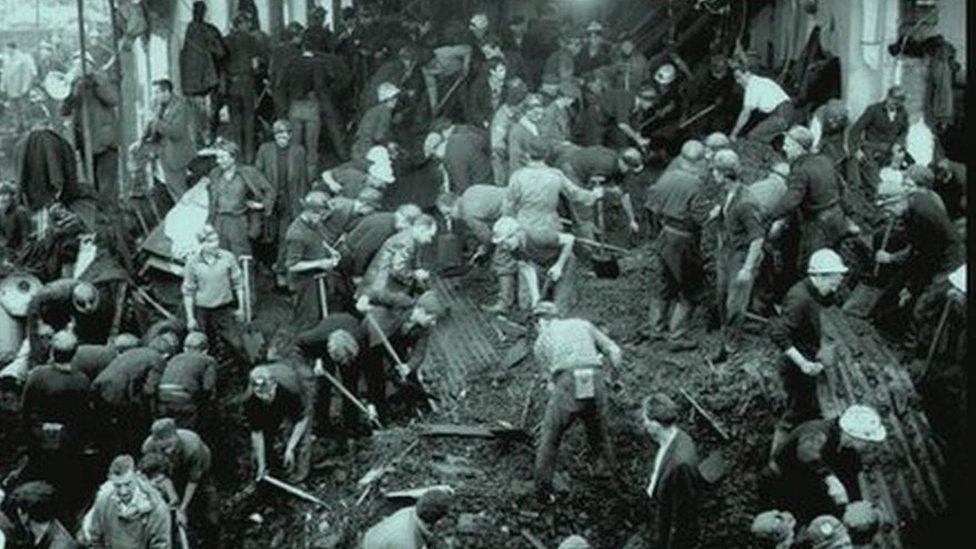

On 21 October 1966, 144 people died when a coal waste tip slid down a mountain and engulfed a school and surrounding houses

Survivors, rescuers and journalists involved in the Aberfan disaster have spoken of their experiences publicly, many for the first time in 50 years, at a conference in Cardiff.

The event, Remembering, Forgetting and Moving On, was organised by Cardiff University's School of Journalism.

It was held as the community prepares to mark the 50th anniversary of a coal waste tip sliding on to the village, external school and 18 homes on 21 October 1966.

It killed 116 children and 28 adults.

People in the audience felt moved to stand up and tell their own stories after hearing from the speakers.

Yvonne Price from Merthyr Tydfil, who was one of the first four police officers at the scene, stood up and revealed she was being treated for post-traumatic stress disorder.

She said on the day of the disaster she had to climb through a window into the school as she was the only person there small enough to do so.

She said she had to clear the way for the others and spent that first day helping pass victims through the windows.

The following morning she was back at the scene, she said, and was appointed as the mortician's assistant after being asked to identify the colour of a child's eyes at the mortuary.

She recalled being given brandy all day long.

She said she had kept it to herself for 45 years but finally "had to get it out of my system" five years ago.

Survivor Jeff Edwards, who went on to become Merthyr Tydfil council leader, was one of the speakers and said he had told his story many times over the last 50 years and that he was now able to talk about it more easily without getting upset.

"Many have been unable to talk about their experience at all, they're still bottling up their anger and frustration within themselves.

"My advice to anyone is to speak about it."

Steve Gerlach, one of three siblings to survive the disaster, was in the audience and said it was the first time he had spoken in public about what happened.

Mr Gerlach, whose family moved to Weston-Super-Mare the year after the disaster, said: "I'm the eldest. My brother, a year younger, was physically injured when he was hit by the slurry. My sister and I walked out fine.

"I hadn't come here with any prepared speech, but it was after hearing what the others said (I wanted to speak)."

He said his family had not discussed it for the first 40 years and he grew up not knowing very much about what happened.

"I teach religious studies and I'm very involved with holocaust studies, I've met survivors, taken children to Auschwitz and I've heard people talking about the need to remember, but it's how we remember that's important as well.

"In some cases remembrance of the holocaust has become an industry and that's difficult for survivors to see their story being packaged and used."

The Queen and Duke of Edinburgh visited Aberfan in the days following the tragedy

Former BBC news editor Elwyn Evans, told the conference he was sent to the scene in his first job on a newspaper.

He said he had spent the last 50 years trying to forget the experience, but chose to speak about it publicly for the first time at the conference.

He was 17 at the time and 21 October 1966 was his last day at the Merthyr Express having undertaken six weeks' holiday relief work with the newspaper.

"People like to say they were the first journalist at the scene. I wasn't a journalist but I was there at one of the worst peacetime disasters of the 20th century," he said.

He added that on a personal note the disaster had made him sensitive to the suffering of others when he went on to pursue a career in journalism.

Veteran reporter Vincent Kane was the keynote speaker at the conference

Veteran broadcaster Vincent Kane, who reported on the disaster and its aftermath, said he felt the community were betrayed by the media.

"Somehow or other after the disaster, as controversy followed controversy, a general climate of opinion developed that the surviving community appeared to be a problem, awkward, greedy and grasping troublemakers," he said.

He said the media failed to expose the lies and say what the real problems were.

"The Aberfan community were the victims not the problem.

"The press, the media, has an abiding responsibility to probe and penetrate, in Aberfan, perhaps Wales' darkest hour in the 20th century, we should have been passionate in pursuit of the truth. Instead, we were pedestrian."

Gaynor Madgwick, who survived the disaster but lost two siblings, has written a book in a bid to get closure.

But she said there were some in the community still not ready to speak about what happened.

She said: "There are people at the moment, one woman is seeing a psychiatrist because she cannot face the 50th anniversary. She knows it will open so many wounds. She doesn't know how she's going to cope.

"Others who are in their 70s, 80s, 90s want to tell their stories because an end is coming."

- Published21 April 2016

- Published11 July 2015