Lost City of Trellech: Man spent life savings on field

- Published

Stuart Wilson told BBC Wales people thought he was "mad" when he bought the field in Trellech

An archaeologist who bet his life savings on a hunch he had found a lost medieval city in Monmouthshire has said people thought he was "mad".

Stuart Wilson, 37, was convinced he had located the site of 13th Century Trellech - once Wales' largest city.

He paid £32,000 for a 4.6 acre (1.86-hectare) field at the edge of the modern-day village and started to dig.

Now, 12 years later, he believes he has revealed the footprint of a bustling iron boom town from the 1200s - and he does not regret his decision.

"I should have really bought a house and got out from my parents' [home], but I thought: 'To hell with my parents, I will stay at home and I shall buy a field instead," Mr Wilson said.

"People said 'you must be mad'," he added.

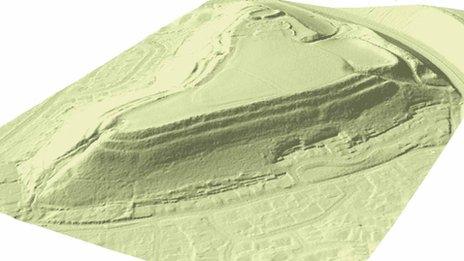

Mr Wilson's site - marked here as 124 - lies to the south of modern-day Trellech

He discovered the site was for sale in 2004, after conducting a dig nearby, and went to the auction armed with his savings.

"It was a close-run thing - it was meant to be a guide price of £12,000 and 30 seconds later it had shot up to £32,000. So it was a very hit-and-miss thing, but eventually we did get it," he said.

Since then he has spent £180,000 in total on the site and enlisted the help of hundreds of volunteers to dig each summer since 2005.

They have uncovered eight buildings, including a fortified manor house and various outbuildings which would have sat alongside the medieval city's market.

Today, Trellech is a somewhat sleepy village with a population of about 2,800.

However, Mr Wilson, a member of Monmouth Archaeological Society, said in the mid 1200s it became the centre of iron production for the army of the de Clare family.

The de Clares were a family of powerful and influential Norman lords allied with Edward I and his bid to conquer Wales.

"At its peak, we're talking about a population of maybe around 10,000 people. In comparison, there were 40,000 in London, so it's quite large," said Mr Wilson, from Chepstow.

"This population grew from nothing to that size within 25 years. Now it took 250 years for London to get to 40,000 people, so we're talking a massive expansion.

"And that's just the planned settlement. The slums [to the east of modern-day Trellech] would have been quite numerous. There you would be talking even 20,000 plus. It's a vast area."

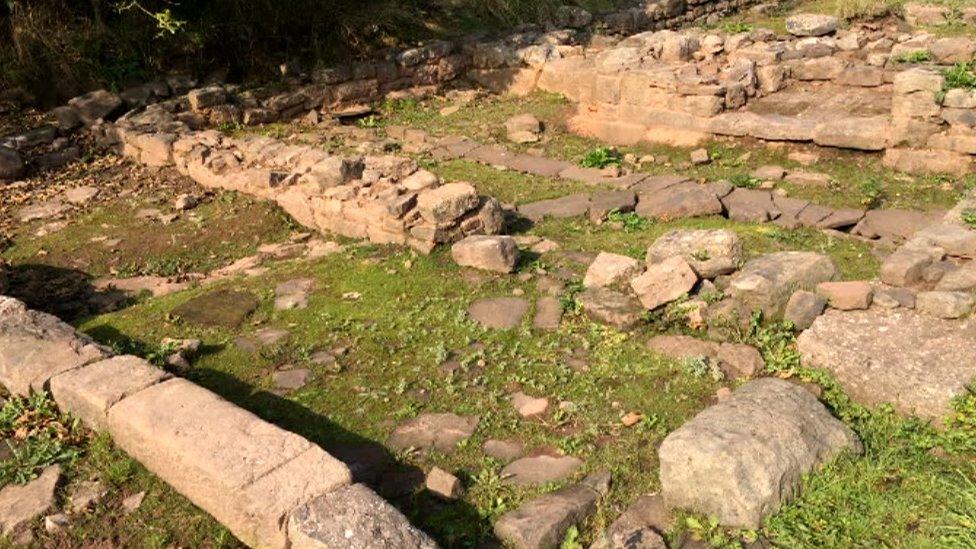

Sections of the historical buildings have been uncovered at the Trellech site

Mr Wilson's field is beside what would have been the medieval market, where iron would have been smelted and goods traded.

He said money and workers would have "poured" into the expanding settlement.

"If you're working in the fields you are living hand to mouth every single day - it's a really hard existence.

"Suddenly, a big industrial town comes here, this is a great opportunity for you.

"You up-sticks - to hell with your land - 'let's move to the industrial town where the opportunity is'."

He said the feudal system would not have been as well developed in the border areas as it was in large parts of England in the 13th Century, so Trellech would have represented a chance for those looking to "rise up the social ranks" more quickly than elsewhere.

"This was like the wild west," he added.

Buildings he has found on the site would have fallen into ruin by 1400 and would have been entirely abandoned by 1650, after the Civil War.

Curiously, the area did not have a rich vein of iron ore and, unusually for such a boom town, it was built on a hill. So how did the industry develop there?

A medieval roof finial and a 15th Century jug found at Mr Wilson's site, known as Tinkers Land

"The primary iron ore came from the Forest of Dean - that's what actually makes it so weird," Mr Wilson said.

"You would normally have taken it down into the gorge and then utilised it at Monmouth or Chepstow, in the valleys and then ship it out.

"You wouldn't then take it back up the hill and then smelted it."

However, the de Clares did not control Chepstow or Monmouth and they wanted to control their own supply of iron to their armies.

Using Trellech was a "strategic power play" which gave them a wide trade route and allowed them to bypass the Welsh defences of the valleys, Mr Wilson said.

However, it is believed the town as it existed then came to an abrupt end in 1296, when it was destroyed during a Welsh rebellion before being subsequently rebuilt.

During the successive digs, Mr Wilson and his team have found scores of artefacts, including a 15th Century jug, a medieval roof finial for "scaring off witches", a rare plant pot and several sharpening stones, as well as silver coins.

Mr Wilson now hopes to turn the site into an attraction and has submitted plans, external for an archaeological research centre and camp site to Monmouthshire council.

But does he feel his financial punt on the site has paid off?

"If I had not found anything it would have been a nice place for a picnic," he said, "but it was not as big a risk as people think."

- Published24 June 2013

- Published7 November 2013

- Published25 January 2014