Holocaust remembrance: Football 'helped save Auschwitz PoW's life'

- Published

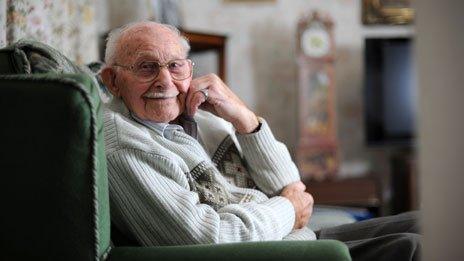

Ron Jones said keeping fit and having a group spirit may have saved the team members during the long march away from the camp at the war's end

A 94-year-old man who survived a prisoner of war camp next door to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp believes a football league which the guards allowed them to set up may have helped save his life.

As Ron Jones, from Newport, prepares to mark Holocaust Memorial Day on Friday with a service at the city's cathedral, he says that amongst all the terrible memories, there will also be a few which will make him smile.

He was captured in 1943 fighting in the Middle East, and after nine months in Italy, was transferred to forced labour camp E715, part of the Auschwitz complex.

There he spent 12 hours a day, six days a week, working with hazardous chemicals in the IG Farben works, but on Sundays they were permitted to play football.

"I think the Germans thought that letting us play football was a quick and easy way of keeping us quiet," he said.

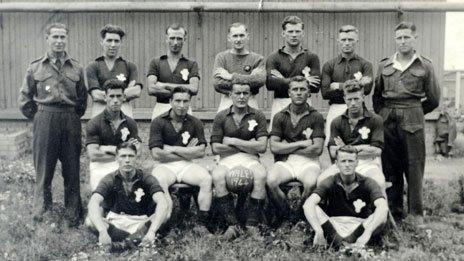

"The Red Cross would bring us food parcels, and when they heard about our football, they managed to get us strips for four teams: England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. I was always the Wales goalkeeper.

"It kept us sane, it was a bit of normality, but it sounds wrong somehow to say I've got fond memories of playing football, considering what was going on just over the fence."

He says as well as keeping up spirits, football played a major role in his survival, and that of many of his fellow prisoners, when they were forced on one of the series of extremely long marches westwards from PoW camps during the final stages of the conflict.

Whilst many of Mr Jones's friends died on the march, he believes it is no coincidence that those who had been involved in the Auschwitz football league fared better.

"You could say the football we'd played saved our lives. The football lads were fitter, yes, but more than that, they belonged to a group which kept each other going on the march."

Ron Jones said those who played football fared better on the long march as the war came to an end

E715 was located close to Auschwitz III, Monowitz, which held mainly Polish resistance fighters, political dissidents, homosexuals and some captured Soviet troops.

Whilst this was not officially a death camp, Mr Jones says it did not take long for him to realise that the inmates at Monowitz were far from safe.

"In the nights you could hear shots coming from Monowitz," he said.

"Not bursts like you had when you were fighting, but deliberate, regular every few seconds; like they had a system going.

"We didn't know who they were or why they'd been killed, and we couldn't help but be terrified that we'd be next."

'Walking skeletons'

But when the British PoWs were allowed out to play football, they would be taken to fields next to Auschwitz II, Birkenau, where killing was on an altogether more industrial scale.

"The first Sunday we went to the playing fields, we saw these people - well walking skeletons they were really - digging trenches," he said.

"We asked, 'Who are those poor sods?' and the German guards shout 'Juden', Jews, as if it had been a stupid question.

"We could only play in the summer, because everything was covered in snow through the winter. But when it was hot, this awful stench would waft across from the crematoriums.

"Your imaginations pretty much filled in the gaps for you, but we'd carry on playing football.

"Scoring a goal, making a save or arguing about an offside was the only way you could stop yourself from cracking up."

Mr Jones says he has spent a great deal of time since the war wondering about how much his German guards had known and cared about what was going on inside Birkenau.

"You have to remember that our guards weren't SS like in Birkenau; they were conscripted squaddies like us," he said.

"Dozens of them would come and cheer our football matches and have a laugh with us, and if you got them on their own, you could tell that they were ordinary, decent blokes.

The labour camp was part of the Auschwitz network of concentration and extermination camps

"But if you asked them about Birkenau they'd get angry and scared. 'We didn't need to know', 'they didn't know', 'it was nothing', and even if it was, then 'it wasn't their fault, they weren't SS'."

"I had nightmares about Auschwitz for years after the war, but I bet mine were nothing compared with what those Germans must have gone through.

"Some would say they deserve it, but most likely they couldn't have done any more about it than we could have ourselves."

As the Red Army closed in, on 21 January, 1945 German guards burst into Mr Jones's hut in the middle of the night, and ordered him to leave immediately with whatever he could carry.

The Soviets liberated Auschwitz on 27 January, 1945, confirming for the first time the stories of the Holocaust's mass murder, which the Allies had hitherto rubbished as too extreme to be possible.

'One of the lucky ones'

But by the time the Russians arrived, Mr Jones was long gone; as part of the death march west, which killed anywhere between 3,000 and 8,000 Allied PoWs.

"We were on the road for 17 weeks, and God knows how many hundreds of miles we traipsed, through Poland, Czechoslovakia, Germany and Austria."

"I was 13 stone (82kg) when I was captured, and when I was liberated by the Americans in April 1945, they weighed me, and I was seven stone."

Mr Jones considers himself one of the lucky ones.

"I was very lucky. I came home to a good wife, who helped me get over it. But lots never really recovered at all," he said.

"I think I'm probably the last now. There was another of the footballers who I got Christmas cards from, but there was nothing this year. So at 94, I think it's probably time to tell the story before it's too late."

- Published23 January 2012

- Published14 December 2011