Port Talbot steel job losses: How town's fortunes have mirrored works

- Published

Steelworkers in Port Talbot, south Wales, find out this week if they are among 750 at the plant to lose their jobs.

As the works - once fondly known to locals as "treasure island" - suffers its latest setback, what does the future hold for the town whose fortunes have mirrored the plant for generations?

June Foley, 79, has seen Port Talbot at its highs and lows.

She has lived in the same terraced house on Gwendoline Street since her parents moved there when she was a baby in 1937.

June was a teenager in the town at a time of huge expansion.

In the early 1950s large areas of dunes were cleared at Sandfields and 900 houses were built specifically to house steelworkers.

Port Talbot's Station Road in the 1960s

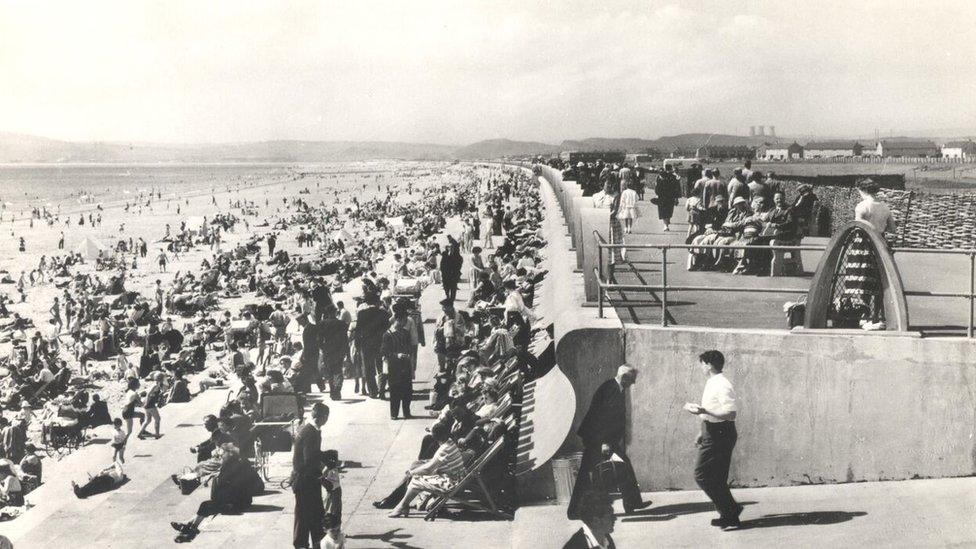

June spent much of her youth on the town's Aberavon Beach.

"We were four friends together. We'd just hang around really, looking for boys I suppose," she remembers.

And it was on the same beach that in 1953, a 17-year-old June met 21-year-old steel works fitter Ted.

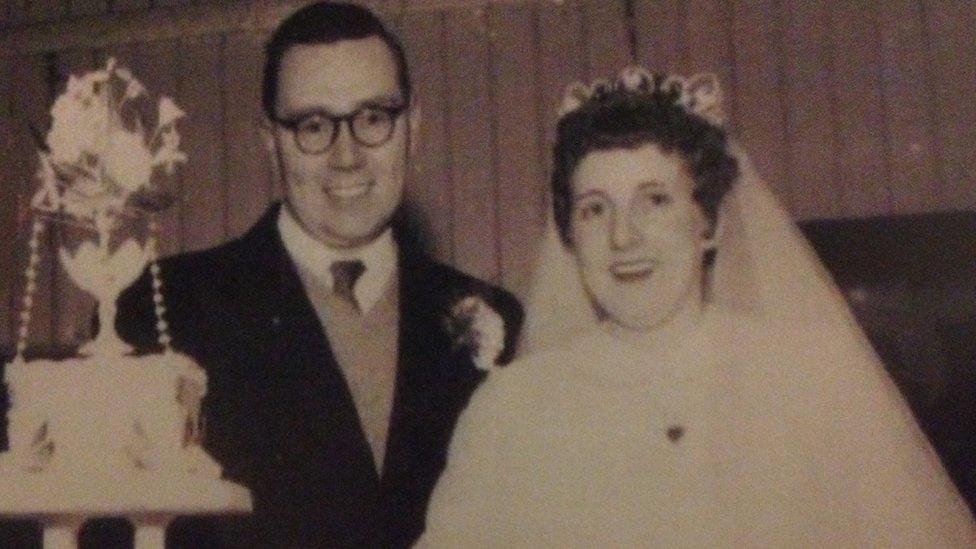

June and Ted Foley were married at Port Talbot's St Paul's Church in 1958

"My father died when he was 43. A day or so later my mother told me 'why don't you go out for a walk'. So I went out on my own... and I met Ted."

June and Ted would go to dances, occasionally visit one of the town's five cinemas or spend time on the then vibrant beach:

"People used to come down from the valleys on the train - in their thousands. There was a funfair, stalls, you could have a cup of coffee or a cup of tea or an ice-cream."

June and Ted married in 1958. In the same year, 20-year-old Betty Wright, now 79, took a job as a shorthand typist at the plant.

Betty worked at the steel works for four years before leaving to have children. Her husband Bernard worked at the plant from the age of 16 to 60 and "loved" the job as well as the socialising at local dance halls and clubs.

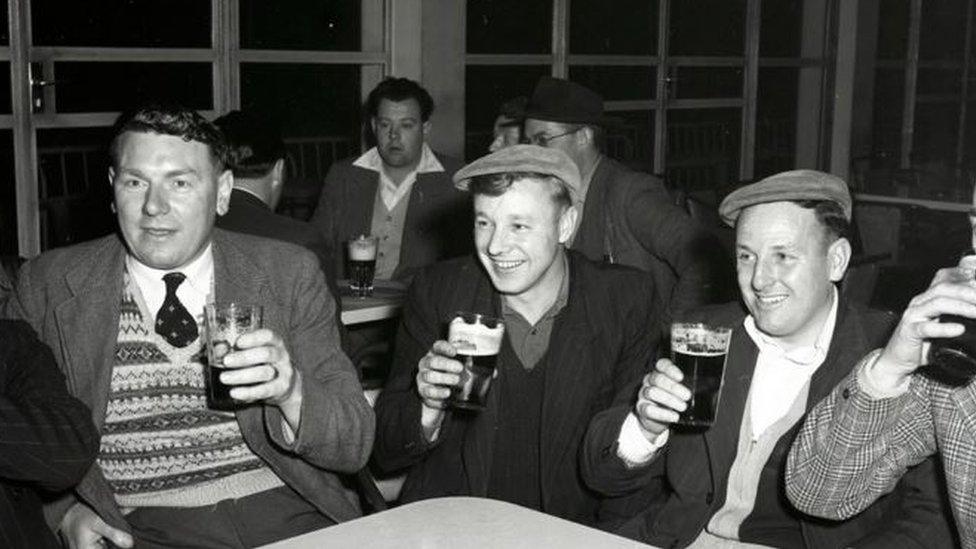

A steelworks staff outing in 1951

"The money was good but you had to put up with the rest of it mind…the smoke from the works. Where there's muck there's brass, they say, and that's true."

The 1950s and 1960s were the "boom years" for Port Talbot, says Bleddyn Penny, a Swansea University PhD student who has interviewed more than 40 former steelworkers, external for his thesis on the history of Port Talbot steelworks.

A labour shortage after the war meant good wages with generous benefits were being offered to entice workers in. At its peak the works employed almost 20,000.

Steelworkers enjoying a drink at the SCOW social club

"Port Talbot steelworkers were the best-paid manual workers in Great Britain," he says.

"If you look at press reports at the time there's a sense of envy of a supercilious nature at the big money Port Talbot steelworkers made and spent on flash cars."

June remembers: "Oh, it was lovely. There were an awful lot of food shops, clothes shops, pubs, you name it, everything."

In 1963, Ted became a foreman at the plant and was on "good money" enabling them to take their three children on holidays.

Aberavon Beach in the 1960s

"Butlins, Pontins, Porthcawl, not extravagant holidays," remembers June.

The Afan Lido was opened by the Queen, external in 1965 and there was a sense Port Talbot was really on the up.

'Silly' strikes

But despite the prosperity, there were hard times too.

Ted was on strike for six months in the 1960s without pay: "Everyone wanted duffle coats, but the works wouldn't give them duffle coats so we went on strike. We had hundreds of silly strikes.

"We had no money. His mother used to give me £2 every Friday so I could go and buy bits and pieces."

Steelworkers enjoy a break in the canteen in the 1960s

Bleddyn says almost all the former workers he spoke to had fond memories of the industry, despite the dangers.

"I asked them what it was like on the first day in the steel works and a lot of them said things like 'it was like stepping into hell' or 'frightening,' yet you ask them if they enjoyed their job and all would go back tomorrow. [There's a] camaraderie being a steelworker."

'So dirty'

When meeting former steelworkers in the town, Bleddyn was struck that the works are almost always visible: "No matter where you were in Port Talbot - Margam, Sandfields, Taibach, Baglan - from everyone's house you can see the steel works.

"And think of the people in Margam who regularly have to clean dust off their cars and windows."

Marion Bowerman, 79, who lives in Margam, knows this first hand.

Aberavon Beach in 1970

"When we built our house we put in white windows, but when they were renewed we put in brown ones. They just got so dirty", she says.

But former steelworker and local councillor Tony Taylor is more pragmatic.

"If you're from Port Talbot you can't afford to worry about that," he says.

"I had white double glazed windows put in. My wife said, 'What's that red dust on them?' and I said 'that's what paid to put them in in the first place'."

'Treasure island'

Tony had the first day of what would be a 44-year career at the plant in 1973.

By now the workforce had been reduced to about 13,500, but it was still a great place to work, he says.

"The steelworks was treasure island. It paid high wages and you didn't need any qualifications... you just turned up, filled your forms in and they took you on."

Councillor Tony Taylor worked at the Port Talbot plant for 44 years

Bleddyn says many former steelworkers tell the same story: "I'm paraphrasing, but someone said to me 'it didn't matter if you left school and couldn't read or if you had a degree - there was a job for you in the works'. All educational abilities were catered for."

'Giro city'

But the 1980s saw a change in fortune for the steel town.

"The Thatcher government came in, the plant wasn't being productive and we had to slim down," says Tony.

"1980 was a watershed moment for the Port Talbot steel industry," says Bleddyn.

"It was the first year when people realised the works seriously might close."

About 6,000 jobs were lost in 1980 and the impact on the town was felt almost immediately.

PhD student Bleddyn Penny has written a thesis on the history of the steel industry in Port Talbot

"That's when the town was labelled 'giro city' - synonymous with people signing on the dole," says Bleddyn.

"The look and feel of the town always mirrors what's going on in the works."

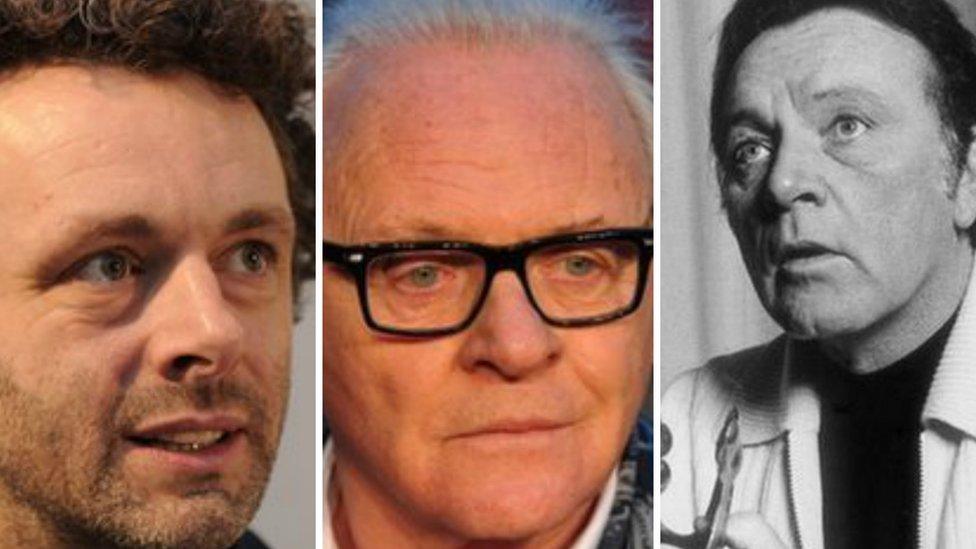

Looming large from the town's now dilapidated Plaza cinema are the faces of the big three local stars - Richard Burton, Sir Anthony Hopkins and Michael Sheen. To many local people, the boarded-up building serves as a monument to Port Talbot's decline.

The Plaza Cinema closed in 1999

Prof Angela Vaughan John, who grew up in Margam, has written a book about Port Talbot's acting phenomenon, The Actors' Crucible, and has identified 50 actors from the town.

She says there are several reasons for this phenomenon: the amateur tradition has strong links to the professional; Port Talbot, despite "feeling like a valleys town" is "brilliantly connected"; and the community has great "educators, teachers and promoters of drama" who have propelled young actors to success.

"I also think emulation is important," she says.

'Drama and steel'

"Rob Brydon [from Baglan] said to me: 'It's not like one person came from the town. You feel maybe I can do something.' That fact that two enormous superstars came from the area [Burton and Hopkins] meant it was possible."

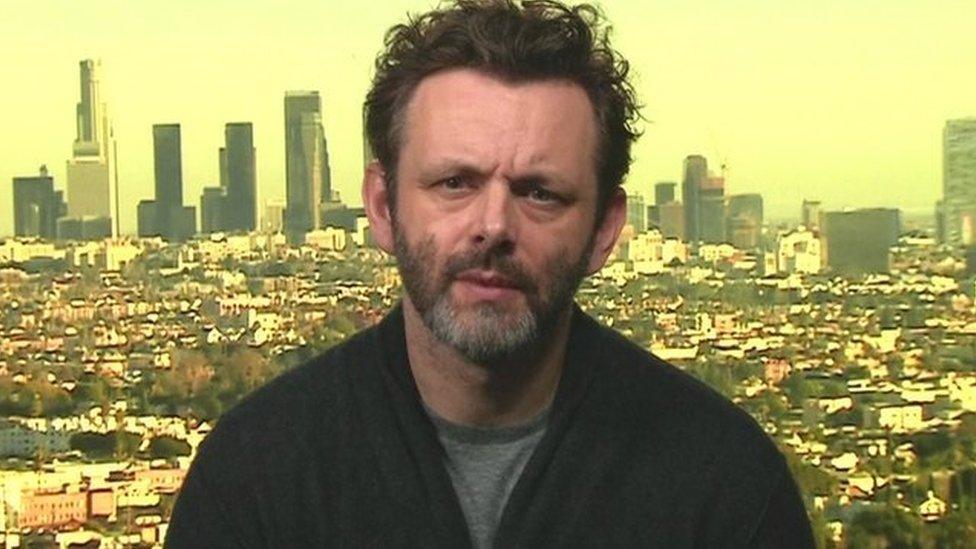

And she spotted a "remarkable synergy" between the town's steel and acting heritage when Michael Sheen appeared on BBC's Newsnight to debate the job cuts with business minister Anna Soubry.

"[They invited] an actor from Port Talbot, not a politician or an industrialist. He is emerging more and more and an effective community spokesperson," she says

Michael Sheen appeared on Newsnight to discuss the Port Talbot job cuts

"That fusion of drama and steel was in one sense exemplified and encapsulated through that programme."

Sheen's father Meyrick, a former Jack Nicholson impersonator and founder of the Port Talbot and District Amateur Operatic Society, says his son gets his passion for the town from the community.

And he gets inspiration from the sight of the steel works at night, his father says: "He loves to go to the mountains and look over at the steelworks... he has this inspiration coming through to him, I'm sure."

On a Wednesday evening in a building tucked behind Taibach's library, the amateur operatic society's youth theatre meets for rehearsals.

Michael Sheen, Sir Anthony Hopkins and Richard Burton all hail from Port Talbot

But despite the singing and laughter, these local children have a lot on their minds.

Nine-year-old Naeve is worried about her dad's job at the steel works: "He doesn't know [if he's lost his job] yet, but if he does it's going to be really hard for us. My mother works, but part-time. I'm a bit sad," she says.

And 15-year-old James is scared his dad could lose his home: "Since my parents divorced that's the house he's been in for 14 years. It's a big deal for the family. I'm not good with change."

Today, Station Road in Port Talbot is home to kebab shops and the town's Wetherspoon

And Ethan, 15, is concerned how the job cuts will impact his generation's career prospects: "There are people about my age and in five years they'll be finishing university and they'll have less opportunities for work."

His parents have a window cleaning business. "It's a luxury to have your house cleaned so that's one thing people are going to have to cut back on," he says.

But despite the uncertainty in the town, Ethan plans to become a nurse and work locally. In fact, most of the children in the group hope to remain in the town long-term.

A union banner was placed outside the Port Talbot plant after the job cuts announcement in January

Regardless of salaries starting at about £30,000, none of the children see the steel works as a career option. Instead, they want to be teachers, actors, writers and lawyers.

But what of Port Talbot's future? Has the town lost a grip on its own destiny? Is there a future for this once prosperous town?

James is not optimistic: "There will be hundreds laid off and it will affect their lives massively. It's hard to say if they'll recover from it. I don't think they will."

The same concerns are shared by the older generation. June and Ted are concerned for their family's jobs. Despite the fact Ted retired from the steel works in the early 1990s, it runs in the blood.

June and Ted have no plans to leave Port Talbot

Two of their sons and one of their grandsons also went on to work at the plant.

June also worries Port Talbot would be "dead" without the steelworks.

"I think the town is horrible now to be honest with you. [Without the works] it would be a ghost town. People won't have the money to spend."

- Published18 January 2016

- Published30 March 2016

- Published19 January 2016

- Published25 January 2016