Shakespeare Schools Festival: All the world's a stage for pupils

- Published

What links William Shakespeare, the fall of the Berlin Wall, coups in Soviet Russia and eight schools in west Wales?

The Shakespeare Schools Festival - an initiative which inspires schoolchildren to perform abridged versions of the playwright's famous work.

From small beginnings, the initiative has grown into the UK's largest youth drama festival.

And as the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death is marked on 23 April, we take a look back at its inception.

"It all started with the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989," co-founder Chris Grace explained.

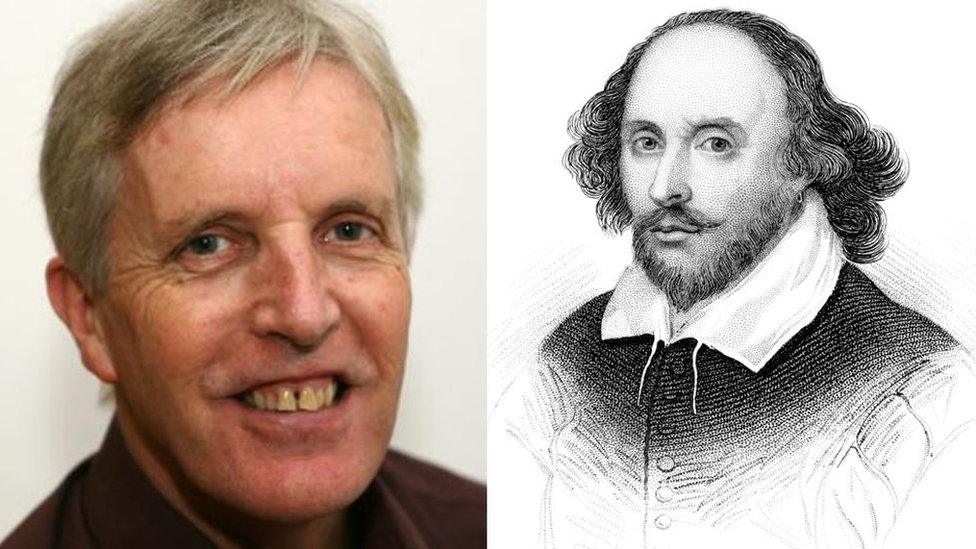

As S4C's co-founder and director of animation, he had already made a name for himself kickstarting the Welsh animation industry with SuperTed and Fireman Sam.

But as eastern Europe opened up, he was inspired by innovative Soviet techniques which used models, drawings and oil on glass.

"I knew there was a Soviet tradition of animation which was totally different to Disney and it opened my eyes to new ways of making content accessible," he said.

"I saw that Shakespeare could be a bridge between east and west; between Soviet tradition and western tradition."

Chris Grace has a BAFTA special award and MBE for services to animation

Working in Moscow, he helped to create 12 half-hour abridged versions of Shakespeare's plays - not an easy task when trying to maintain the original dialogue - with each one costing £500,000 to make.

It was a turbulent time, with production surviving two attempted presidential coups - against Mikhail Gorbachev in 1991 and Boris Yeltsin in 1993.

On one occasion, filming had to be stopped as tanks rumbled by outside, shaking the studio.

On another, the studio came under fire from rebels, with bullet holes peppering the walls.

"It was very exciting on one level because it was a new Europe," he said.

"But it was also fearful. You didn't know the price of bread let alone what the cost of production was.

"Despite this, we established a really strong production and international friendship between Wales and Russia."

The 12 films, known as S4C's Shakespeare: The Animated Tales, were created in Welsh and English. Initially launched at the Royal Academy in London and City Hall in Cardiff, they went on to be released in 70 countries and won three Emmy awards.

By the late-1990s, the films had a "huge up-take" in schools, introducing pupils to Shakespeare "for the very first time".

"Everybody wants something new, especially critics, and animation had never been seen in this way before," Mr Grace said.

"Part one was making Shakespeare accessible through a contemporary medium and part two was to take those films being used by schools and make Shakespeare accessible to young people through performance.

"I thought, 'if they're watching them, why can they not perform them?'"

And so, in 2000, the festival was officially launched.

Living in Pembrokeshire, he arranged for eight schools to perform at the Torch Theatre in Milford Haven.

Each performed a half-hour play to sell-out audiences over two nights.

Liam Barnes, Paris in Romeo and Juliet

"It's not often we get things first in Pembrokeshire, so being the venue for a national debut felt like a major honour.

"Our director was a bit individual, not to mention notorious in my family for constantly giving me detentions, and she decided to set a Japanese theme around this classic love story from Verona.

"When not on stage, all the cast had to stand rigidly around the edge of the stage and even in an abridged version this was pretty uncomfortable.

"Despite the strains of performing I remember the cast getting along very well. One of the twins playing Juliet had a brief romance with an actor other than Romeo, while I quietly held a candle for Lady Capulet until she moved to a different school years later - parting is such sweet sorrow, as someone once wrote.

"There was a palpable sense of achievement on the final night as the applause rang out.

"Seeing it carry on and spread across the country should be a point of pride for all the pupils involved."

Peter Doran, artistic director at the Torch Theatre

"The theatre had seen a lot of Shakespeare already but this was something completely different; eight schools performing eight Shakespeare plays.

"I thought it was a bold idea but what appealed to me was this idea of schoolchildren learning and really engaging with Shakespeare.

"It was quite difficult because you have to tell a story within half an hour but that's part of its success. It has to be told in a very short and simple way.

"The theatre was filled with mums, dads, aunts, uncles and grandparents. There was a real buzz around the place.

"It proved just how well it could work."

"One play I remember in particular was Romeo and Juliet in which they wore Japanese costumes," Mr Grace recalled.

"They used the technique of kneeling down and drumming the floor with their hands to create the atmosphere of fighting.

"Then, when Juliet committed suicide, the young girl ripped a huge tear in her kimono.

"The quality of each performance was outstanding."

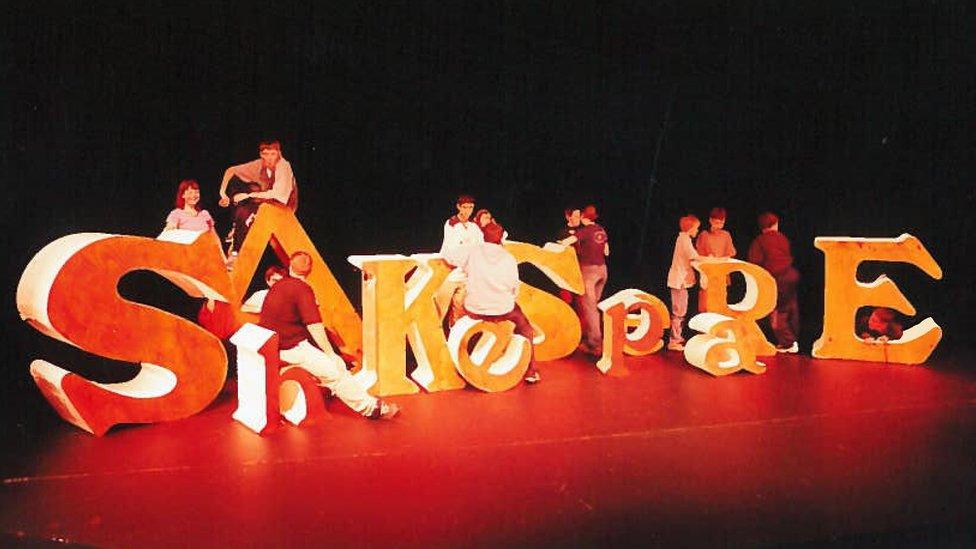

The idea of children performing Shakespeare grew from there - by 2001 it had expanded to London, a year later to the whole of Wales and by 2007 right across the UK.

The festival even spread its roots to South Africa in 2011 and has since expanded to schools in five cities.

Fast forward to 2016 and 30,000 pupils from more than 1,000 primary, secondary and special schools are set to perform in 130 theatres all over the UK, including 15 in Wales.

Its success has won the support of high-profile patrons, including Oscar winner Dame Judi Dench, dramatist Sir Tom Stoppard and author Philip Pullman.

"Children feel clever for having learnt the language and cracked it, while teachers say they are amazed to see children who are shy and mute come alive on stage," Mr Grace said.

"I think it's important because Shakespeare is a part of our legacy and our cultural heritage. His stories are as relevant now as when they were first written.

"The themes, the characterisation, the humour, the drama; it's all as alive now as it was all those years ago."

- Published2 November 2010