Swansea scientists make antihydrogen breakthrough

- Published

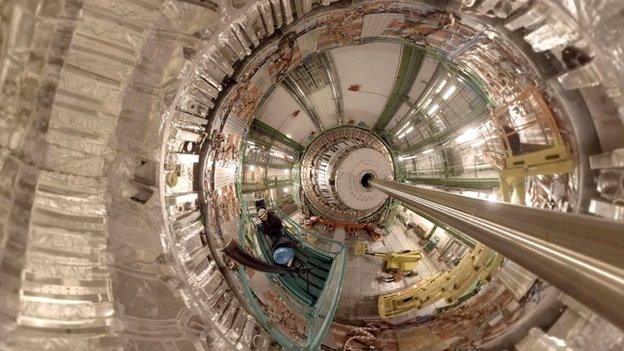

The team made the discovery at Cern's particle physics laboratory in Geneva, Switzerland

A team from Swansea University is one step closer to answering the mysteries of antimatter and the Big Bang after making a scientific breakthrough.

Scientists from the university's College of Science have created and measured the properties of antihydrogen for the first time.

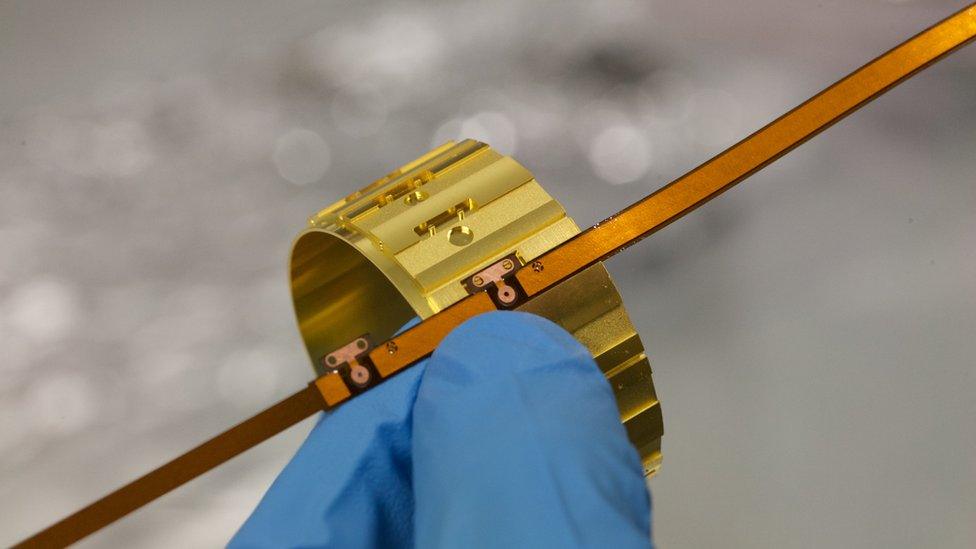

Using super-cooling techniques, they reduced particles' energy, assembled them into anti-atoms and captured them.

Their findings were published in science journal Nature, external.

The team made the discovery at Cern's particle physics laboratory, external in Geneva, Switzerland.

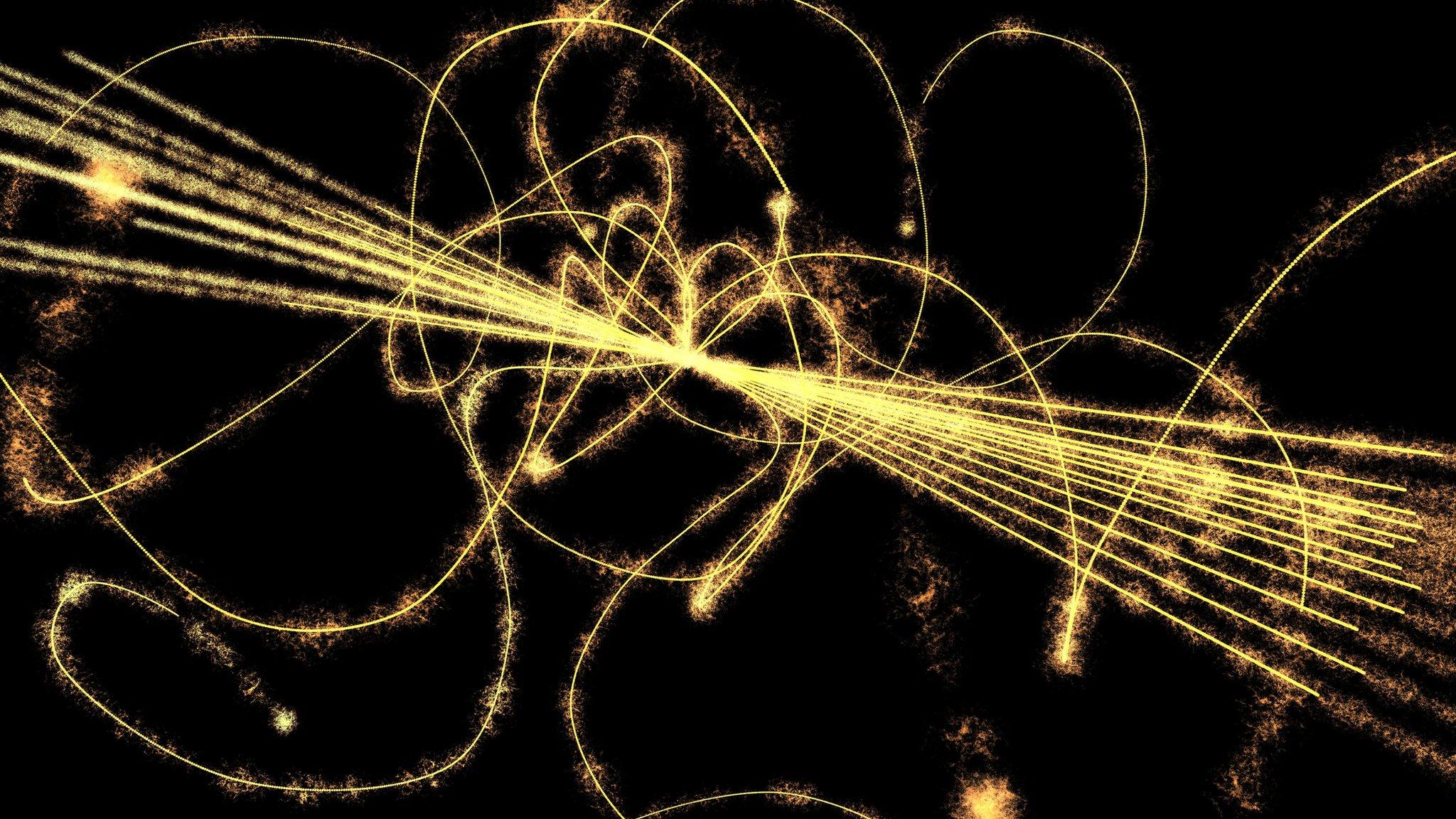

Antimatter is essentially the same substance as matter - everything around us - with the charges of its particles reversed. Antihydrogen is the antimatter equivalent of hydrogen.

At the beginning of the Universe, the Big Bang produced matter and antimatter in equal amounts. But antimatter is so rare that no lasting examples have been detected outside of the laboratory.

The university's Prof Niels Madsen explained: "In some ways we still don't understand why the universe exists at all, as when matter and antimatter come into contact they are instantly converted into energy and both particles are annihilated."

Scientists have observed antimatter particles since the 1930s

It is this inherent instability which has made antimatter so difficult to create, capture and study.

Since the mid-1990s, scientists have known how to create entire atoms of antimatter, or anti-atoms.

However, these have lasted for just a fraction of a second and had to be held by magnetic fields suspended in a vacuum as they cannot come into contact with any matter.

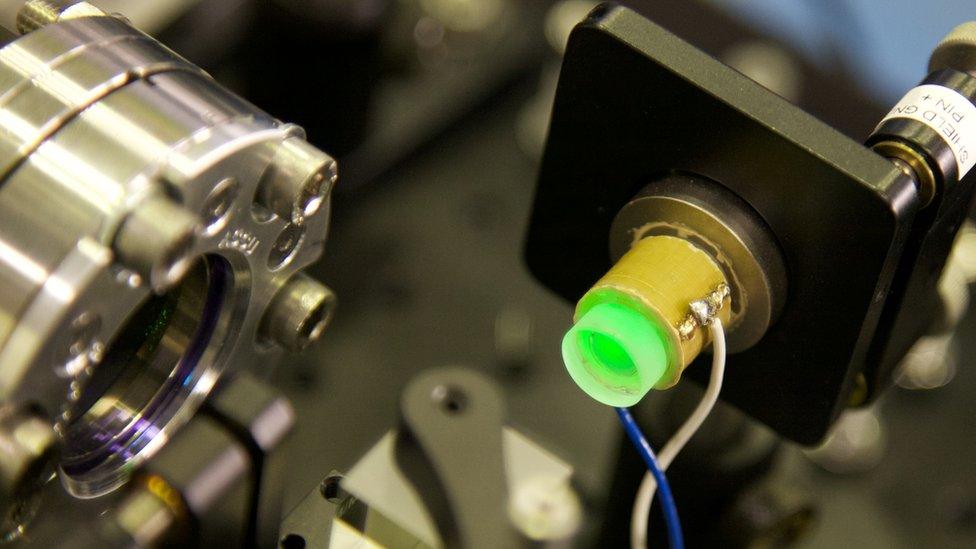

This new breakthrough means the team can measure the energy given off in the form of light to try and see if there are any differences between hydrogen and antihydrogen, which could offer clues as to the scarcity of antimatter.

"We really don't know for certain but we are working on the hypothesis that for there to be such a discrepancy between matter and antimatter, there must be a very subtle difference in their structure," Prof Madsen said.

The Universe consists primarily of matter and not antimatter

The team are currently able to measure with an accuracy of four decimal places on the so-called hyperfine transition scale.

But to conclusively test their hypothesis they hope to improve this to 12 decimal places, something which will be complicated by the magnetic field in which the antihydrogen has to be suspended.

"Who knows how long it will take, or even if we'll ever find a difference," said Prof Madsen.

"It's like a Medieval explorer heading off across the seas to find a new continent, without knowing if it even exists; but without looking how will you ever know?"

- Published11 March 2016

- Published20 March 2017

- Published12 June 2010