Viewpoint: Religious freedom is not tolerance

- Published

Here's an essay question, students: Religious freedom and religious tolerance are not the same thing, or are they? Discuss.

The reason for asking the question today is obvious. The plan to build Park 51, a Muslim community centre a few blocks north of Ground Zero in New York City, has re-kindled resentment smoldering since 9/11 against the Muslim community in a significant portion of American society.

Two-thirds of those questioned for a New York Times poll said a mosque should not be built at the site

Toleration seems to be in short supply, with reports of several mosques being vandalised around America and a Muslim cab driver in New York being knifed because of his religion.

In a poll of New York City residents for the New York Times, published on 27 August, 72% of those interviewed told pollsters people have the right to build a house of worship near Ground Zero.

No surprise there, that's what religious freedom means.

But when asked, "Do people have the right to build a mosque and Islamic community center near ground zero?" the number dropped to 62% saying OK.

Finally, when asked should the Park 51 mosque and community centre actually be built at the proposed site, 67% said No.

The question raised by the poll is, people have religious freedom but where did the toleration go?

Endurance

In an editorial, the Times' expressed dismay and concluded: "The mosque should be built in Lower Manhattan because moving it would compromise American values."

Where do those values of religious tolerance come from? Are they uniquely American? Here's a bit of history.

John Locke: Anyone who is honest, peaceable and industrious, is OK

The word tolerance applied to religion was one of the foundations of the Enlightenment. Back in the 17th Century, after 300 years of murder, torture, war and general mayhem committed by Catholics and Protestants, some thinkers began to consider a better way for humanity.

Religion and politics had become too intertwined. It was time to uncouple them.

The English political philosopher, John Locke, living in exile in Amsterdam - having fallen foul of religious/political intrigues back home - wrote a Letter Concerning Toleration which was published in 1689.

In it, he wrote: "Neither Pagan nor Mahometan, nor Jew, ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the commonwealth because of his religion... The Gospel commands no such thing... and the commonwealth which embraces indifferently all men that are honest, peaceable, and industrious, requires it not."

Now, before we get all misty-eyed and think Locke's essay is the 17th Century version of children holding hands and singing "We Are the World" you have to understand that "toleration" as it was used by Enlightenment philosophers comes from the Latin word tolerare meaning "to endure".

It is closer in meaning to the phrase "high pain tolerance" rather than something noble and generous. We endure our minorities for the better functioning of the commonwealth.

The French model

Over the century following publication of Locke's letter, the word migrated into European political discourse.

No US government will ban the full Muslim veil in public buildings, as France has

Giving religious minorities their rights became important to creating modern states.

"Toleration" meant permission given by the authorities for minorities to have certain rights guaranteed. For example, Toleration Letters from various rulers gave Jews the right to live outside the ghettos into which they had been segregated for almost 500 years.

It was this understanding of religious toleration that the Founding Fathers had in mind when they wrote the language on religious freedom that appears in the first amendment of the American Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

The same understanding of tolerance was used just after the fall of the Bastille, when the French National Assembly wrote a new constitution for France that included, for the first time in European history, a guarantee of full citizens' rights for its Protestant and Jewish minority.

But with those civil rights came an expectation from the majority. Jews would have to become French.

They would have to stop wearing their traditional clothes and be educated in French schools. Their Rabbis would have to become fluent in French. Legal precedents were set to make sure this happened.

These same precedents are the basis of the French National Assembly's decision this summer to ban the full Muslim veil in public places.

The American definition of liberty means the government would not take the same position as the French government - although I suspect plenty of Americans would like to ban the hijab and the veil.

Empire

In the furor over Park 51, the more thinking members of the anti-mosque brigade have invoked French reasoning without using the word France, reminding the project's prime mover, Imam Faisal Abdul Rauf, that tolerated minorities have reciprocal responsibilities not to tread to heavily on the feelings of the majority.

Where equality fits into their reasoning is not clear.

Curiously Britain, which had no 18th Century revolution and which still bans a Catholic from taking the throne, has had in these times of tensions between Muslims and their fellow citizens, fewer problems.

Despite the bombings of 7/7 and several subsequent near-miss plots, and although its Muslim population is primarily composed of immigrants from Pakistan, a country where radical Islam has a strong foothold, there seems to be, for want of a better word, tolerance.

Tensions simmer, make no mistake. Prominent national newspaper columnists turn the heat up with their talk of London-istan, and there were isolated riots in the north of England in 2001 - though these were more over economic issues rather than faith or religion.

In last May's election, the British National Party, which melds Islamophobia with a general anti-immigrant stance, actually lost seats on local councils.

First encounter

My theory as to why, when America is on the verge of exploding with intolerance towards Muslims, Britain seems to be coping, has less to do with political philosophy than a basic historical difference.

Through its empire, British society had several centuries of extensive contact with Muslims. People in Britain may have prejudice against Muslims but they don't have the same visceral intolerance that is often the first response when people encounter someone alien.

After World War II and the end of Empire any wave of immigration from the former colonies back to the "Mother Country" became news.

Muslim immigration, primarily from Pakistan but also Uganda, was no different. It was examined thoroughly in the press and in university social science departments.

Following the oil price shock of 1973, wealth flowed to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States and London became the preferred destination of the newly-wealthy citizens of those countries in summer and also in times of instability.

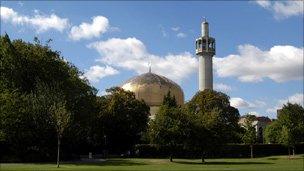

London's Central Mosque, in Regent's Park, was first mooted in the 1930s

Britons have had decades to get over their initial reactions to seeing men in starched thobes or dishdashas and women wearing the veil walking the streets of London.

Prior to 9/11, my guess is that most Americans didn't realise there were up to two million Muslims living in their country and they certainly didn't know or think much about Islam at all... just as they don't know or think much about the world outside the US.

So their first encounter with Islam has been through its most violent and radical adherents. That's not a good introduction.

But how does this answer the essay question I posed at the start of this piece?

Officially in Britain, there is an established church and an official inequality of religious freedom at the highest level, but tolerance seems to be thriving.

In America, the idea of religious freedom remains paramount, yet intolerance seems to be on the rise. Far too many insist on saying the US is a "Christian" country without considering what that means for those of us who are Americans but not Christian.

The answer I offer is that religious freedom needs to be guaranteed by law - as it is in the American Constitution - because religious tolerance is variable, something we cannot rely on our fellow citizens to practise as a matter of course.

Michael Goldfarb, external is a journalist and broadcaster who has lived in London since 1985. Formerly with National Public Radio, he is now the London correspondent of globalpost.com, external.

- Published1 September 2010

- Published20 July 2010

- Published5 August 2010