A journey from Hudson Bay north to the Canadian Arctic

- Published

Inside a Canadian Arctic cargo ship

Canada is staking its claim to Arctic waterways and mineral resources - as are Russia, the US, Norway and other regional powers. All are meeting in Moscow this week in an attempt to head off an international dispute.

Just before midnight and in the cold of approaching winter, we boarded the Hudson Bay Explorer in the Arctic port of Churchill. Tethered to our 110ft tug by a heavy steel cable was an enormous barge, laden with vehicles, construction materials, even a metal shed.

We were to tow this north towards the Arctic Ocean and to the isolated communities that live along the western shore of the Hudson Bay. It's a landscape of tundra, inaccessible by roads: ships like this are a lifeline for Canada's remote north.

As we ploughed through the inky night in our small tug, I rolled around in a top bunk to the sound of engines churning.

In the morning, I could see nothing in any direction - no land, no ships - just the slate grey of the sea.

Seasonal ice

Hudson Bay is enormous - more than three times bigger than the UK - and here we were, a tiny speck, 20 miles west of the coast, heading north. Our destination was barely 150 miles from our starting point, but at a speed of less than 7 knots and hauling thousands of tonnes through agitated seas, it was going to take us a long time.

Still, in a few weeks this journey won't even be possible. This corner of Hudson Bay is the first to freeze; soon ice will choke or cover the sea all the way up to the North Pole.

In the far north, ice is permanent. At lower latitudes it is seasonal. And as the earth warms up, polar ice is melting more quickly and over a greater area. In fact latest surveys recorded the amount of summer polar ice at the third lowest level on record.

The result is that in the summer, stretches of sea that are normally blocked are now opening up to shipping.

"Global warming is going to change the face of the north," Captain Richard Lambert told me on the bridge of the Hudson Bay Explorer. He has nearly 40 years experience in this business, and he predicts upheaval.

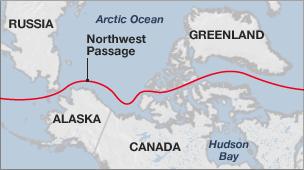

"The tug and barge industry will be reduced because larger ships can come and they will bring more cargo in bulk," he said, "Ships are going to be able to leave Atlantic Canada and go to the Pacific coast through the north, which they could never do before. The Northwest Passage was open last year. A couple of tugs did get through."

The Northwest Passage is the holy grail for shipping.

For centuries sailors searched in vain for an Arctic shortcut between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It would slash weeks off journey times and millions off costs; this was commercially valuable and strategically important.

Patrol boats

In recent summers, the Northwest Passage has been ice-free.

And consequently there's a contest for control.

"We live in a time of renewed interest in Canada's Arctic," declared Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper last month.

He was speaking during military exercises in the Arctic, staged as a show of strength. Canada is also buying new patrol boats for the area.

"All these efforts are toward one non-negotiable priority," Mr Harper said, "and that is the protection and promotion of Canada's sovereignty over what is our North."

It was a strong assertion of Canadian sovereignty over Arctic waterways including the Northwest Passage.

But it's a disputed claim.

Even though it lies between Canadian-controlled islands, Canada's Arctic neighbours America and Russia argue the Northwest Passage should be freely accessible to international shipping.

Few believe the frogmen and helicopters Canada showed off in Resolute Bay last month will ever be pressed into service over this argument, but it is a key issue this week's summit must address.

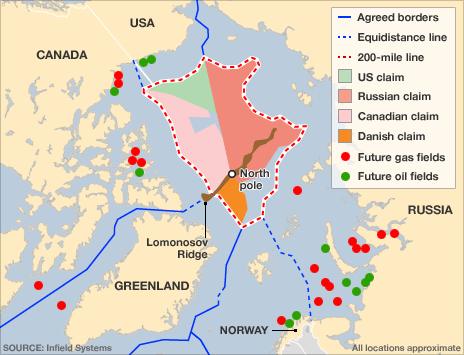

Also on the table for Canada - and others - are disagreements over borders.

On the east coast, who controls a tiny lump of rock called Hans Island that lies between Canada and Greenland?

In the west, does the land border with the US state of Alaska extend into Arctic seas? Or should a new one be drawn?

Establishing territory allows countries to start exploring the vast oil and gas deposits under the Arctic seabed. It's estimated as much as a quarter of known reserves could lie in this daunting environment, but with high energy prices and rocketing demand from ravenous Chinese and Indian economies, Arctic nations are keen to get drilling and reap the benefits.

It seems a world away from the cramped confines, the diesel aftertaste and the gut-churning pitch of the Hudson Bay Explorer. After 20 hours at sea finally the ship dropped anchor at our destination, the Inuit town of Arviat.

There is no jetty, so at high tide the tug pushed the barge onto the dark brown beach, where low-tide left it grounded. Ramps were deployed and the vehicles and cargo rolled straight onto the shoreline.

Dirt roads

Arviat is the furthest south of a string of isolated communities - mainly Inuit towns - running up the Hudson Bay and along the Arctic Ocean shores.

Supporting remote communities like this is another way Canada can show who is in charge up here, demonstrating to the world that the Arctic is a region populated, sustained and defended by Canadians.

Government strategy includes the social and economic development of communities in the north. (The shipping company we travelled with, NTCL, is owned by First Nations or native communities and is the largest in northern Canada.)

Temperatures in Arviat can drop to -40C in winter

We met Tony Uluatluak, who was waiting with his wife and children for their new car to come off the barge. He is from the largest Inuit family in town - his parents have 192 grandchildren.

"Do you feel part of Canada," I asked.

"We are 100% Canadian," he told me, "proud to be Canadian."

We walked into Arviat through a cold, damp mist.

It's a place built for practicality where temperatures can drop to -40C in winter. The dirt roads were unpaved, lined with weathered wooden houses.

Boats and skidoos lay alongside. Outside one house animal skins were hanging. Above another, a Canadian flag fluttered.

Here, they hunt caribou and seals and are allowed a quota of whales. If polar bears come into town - as I was told they often do - they are fair game too.

Here, traditional and modern ways of life coexist.

There's a KFC branch and I saw people riding around on all-terrain vehicles, yet many women wore traditional long coats with large hoods in which they carried babies.

As in many northern communities, alcohol is not allowed but everyone smokes.

The Inuit language Inuktitut is more widely spoken than English, even though the Queen is on the banknotes. In written form it appears in elegant, almost geometrical shapes.

Both languages were equally prominent on many signs around town.

Canada supports strong native traditions - it's also a way of reinforcing its ownership of the north.

But the people need the government as much as it needs them. There are few jobs, prices are high and many depend on benefits.

At the large grocery store that is the town's focal point I met Chesley Aggark, his wife Shauna and their three children carrying two loads of shopping to their ATV.

They told me one week's groceries cost them more than 500 Canadian dollars (£310.)

I asked them how they could afford it.

Shauna pointed down: "with the help of my children," she said, "child benefit… income support."

"Could you survive if the government didn't help you," I asked.

"No," she said.

After delivering cargo to Arviat, our boat headed further north to another community, carrying the last precious supplies before winter's freeze.

We hitched a ride on another tug back to Churchill and two days later our journey was over.

But the gold rush in the Arctic is just beginning and I saw first hand how Canada is staking its claim.

- Published22 September 2010

- Published21 September 2010

- Published22 September 2010

- Published15 September 2010