Uncertainty surrounds Japan's nuclear picture

- Published

Police are trying to clear residents from the evacuation zone around the Fukushima plant

The word "meltdown" goes to the heart of the big nuclear question - is nuclear power safe?

The term is associated in the public mind with the two most notorious accidents in recent memory - Three Mile Island, in the US, in 1979, and Chernobyl, in Ukraine, seven years later.

You can think of the core of a Boiling Water Reactor (BWR), such as the ones at Fukushima Daiichi, as a massive version of the electrical element you may have in your kettle.

It sits there, immersed in water, getting very hot.

The water cools it, and also carries the heat away - usually as steam - so it can be used to turn turbines and generate electricity.

If the water stops flowing, there is a problem. The core overheats and more of the water turns to steam.

The steam generates huge pressures inside the reactor vessel - a big, sealed container - and if the largely metal core gets too hot, it will just melt, with some components perhaps catching fire.

In the worst-case scenario, the core melts through the bottom of the reactor vessel and falls onto the floor of the containment vessel - an outer sealed unit.

This is designed to prevent the molten reactor from penetrating any further. Local damage in this case will be serious, but in principle there should be no leakage of radioactive material into the outside world.

But the term "in principle" is the difficult one.

Reactors are designed to have "multiply redundant" safety features: if one fails, another should contain the problem.

However, the fact that this does not always work is shown at Fukushima Daiichi.

The earthquake meant the three functioning reactors shut down. But it also removed the power that kept the vital water pumps running, sending cooling water around the hot core.

Diesel generators were installed to provide power in such a situation. They did cut in - but then they cut out again an hour later, for reasons that have not yet been revealed.

In this case, redundancy did not work.

And the big fear within the anti-nuclear movement, as used in the film The China Syndrome, is that the multiple containment of a molten core might not work either, allowing highly radioactive and toxic metals to burrow into the ground, with serious and long-lasting environmental impacts - total meltdown.

However, the counter-argument from nuclear proponents is that the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island did not cause any serious effects.

Yes, the core melted, but the containment systems held.

And at Chernobyl - a reactor design regarded in the West as inherently unsafe, and which would not have been sanctioned in any non-Soviet bloc nation - the environmental impacts occurred through explosive release of material into the air, not from a melting reactor core.

To keep things in perspective, no nuclear accident has caused anything approaching the 1,000 short-term fatalities stemming from Friday's earthquake and tsunami.

'Subcritical' reactors

Whether a partial meltdown is under way at Fukushima Daiichi is not yet clear.

The most important factor is summed up in a bulletin from the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) that owns the facility: "Control rods are fully inserted (reactor is in subcritical status)."

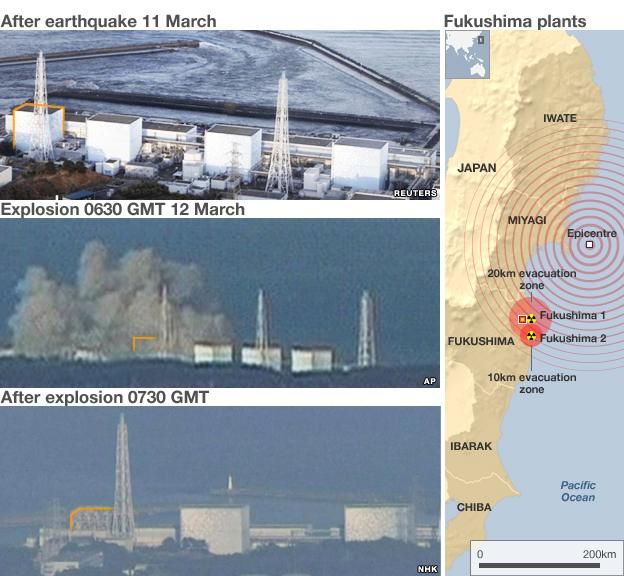

A large explosion was seen at the plant with debris blown out from the building

Control rods shut off the nuclear reaction. Heat continues to be produced at that stage through the decay of radioactive nuclei - but that process in turn will begin to tail off.

Intriguingly, Ryohei Shiomi, an official at Japan's Nuclear Safety Commission, is widely quoted as having said a meltdown was possible and that officials were checking.

Meanwhile, a visually dramatic explosion in one of the reactor buildings has at least severely damaged the external walls.

In principle, this should not cause leakage of radioactive material because the building is just an outside shell; the job of keeping dangerous materials sealed in falls to the the metal containment vessel inside.

Chief cabinet secretary Chief Yukio Edano confirmed this was the case, saying: "The concrete building collapsed. We found out that the reactor container inside didn't explode."

He attributed the explosion to a build-up of hydrogen, related in turn to the cooling problem.

Under pressure

The only release of any radioactive material that we know about so far concerns venting of the containment vessel.

When steam pressure builds up in the reactor vessel, it stops some of the emergency cooling systems working, and so some of the steam is released into the containment vessel.

However, according to World Nuclear News, an industry newsletter, this caused pressure in the containment vessel to rise to twice the intended operating level, so the decision was taken to vent some of this into the atmosphere.

In principle, this should contain only short-lived radioactive isotopes such as nitrogen-16 produced through the water's exposure to the core. Venting this would be likely to produce short-lived gamma-ray activity - which has, reportedly, been detected.

One factor that has yet to be explained is the apparent detection of radioactive isotopes of caesium.

This is produced during the nuclear reaction, and should be confined within the reactor core.

If it has been detected outside the plant, that could imply that the core has begun to disintegrate.

"If any of the fuel rods have been compromised, there would be evidence of a small amount of radioisotopes in the atmosphere [such as] radio-caesium and radio-iodine," says Paddy Regan, professor of nuclear physics at the UK's University of Surrey.

"The amount that you measure would tell you to what degree the fuel rods have been compromised."

It is an important question - but as yet, unanswered.

Cover-ups and questions

In fact, the whole incident so far contains more questions than answers.

Parallels with Three Mile Island and Chernobyl suggest that while some answers will materialise soon, it may takes months, even years, for the full picture to emerge.

How that happens depends in large part on the approach taken by Tepco and Japan's nuclear authorities.

As with its counterparts in many other countries, Japan's nuclear industry has not exactly been renowned for openness and transparency.

Tepco itself has been implicated in a series of cover-ups down the years.

In 2002, the chairman and four other executives resigned, suspected of having falsified safety records at Tepco power stations.

Further examples of falsification were identified in 2006 and 2007.

In the longer term, Fukushima Daiichi raises several more very big questions, inside and outside Japan.

Given that this is not the first time a Japanese nuclear station has been hit by earthquake damage, is it wise to build such stations along the east coast, given that such a seismically active zone lies just offshore?

And given that Three Mile Island effectively shut down the construction of civilian nuclear reactors in the US for 30 years, what impact is Fukushima Daiichi likely to have in an era when many countries, not least the UK, are looking to re-enter the nuclear industry?