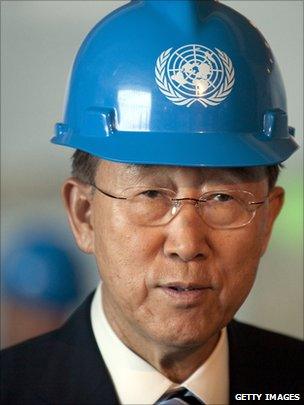

Why Ban Ki-moon is tipped for new UN term

- Published

When Ban Ki-moon faces a UN General Assembly vote on his re-nomination Tuesday, he is pretty much guaranteed a second five-year term. He has no competition and virtually no opposition.

But it didn't always look as if it would be so easy - he has been subject to some extraordinarily sharp criticism since taking over the top job at the world body in 2007.

Mr Ban's low-key style set him apart from his outspoken predecessor Kofi Annan, who ran afoul of the Bush administration by declaring America's war in Iraq illegal, and who was described by some as the "secular pope" for his championing of human rights.

The former South Korean foreign minister quickly made it clear that he preferred quiet diplomacy to the bully pulpit.

He has earned a reputation among diplomats as a diligent, hard-working and serious leader, who believes strongly in consensus and harmony - values shaped, some say, by his Asian culture. He is someone who has "proven he's committed to seeing the job through and will work tirelessly to get it done right," according to Ted Turner, who heads the UN Foundation.

Explaining to journalists why he wanted a second term, Mr Ban promised to keep leading the UN as "bridge-builder".

He cited as his achievements his efforts to put climate change at the top of the world agenda, overseeing the UN's response to several devastating humanitarian emergencies, and being an advocate for the world's poor amid the global economic crisis.

But observers say perhaps his greatest success has been to maintain good working relationships with the five permanent members of the Security Council, whose unanimous endorsement he needs for a second term.

Despite a few run-ins - notably with Russia over his handling of Kosovo's independence from Serbia - Mr Ban has been careful not to upset all of the five on any one issue.

For many, however, that strength is his principal weakness. Human rights groups in particular have criticised him for being too willing to accommodate the world's powers.

He is generally viewed as one of the most pro-American secretaries general ever, an attitude apparently rooted in his childhood experience as a displaced person during the Korean War who survived largely on US food donations.

"He sees the Americans as quite a positive force on the world scene, an indispensable nation," says Colum Lynch, a long-time UN correspondent for the Washington Post and blogger for Foreign Policy Magazine.

That extended to enthusiastic backing of the US "war on terror" policy and its continuation under President Barack Obama, says Mr Lynch.

"There was very little criticism of excess," he says. "During his tenure I think you'd be hard pressed to find criticism of drone attacks in Pakistan and Yemen, the kind of cross-border military operations that much of the world finds concerning."

Mr Ban has also been criticised for being deferential to China, coming under heavy attack from activists for failing to take a public stand on the jailing of Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo.

And some diplomats have been scathing about his entire non-confrontational approach.

In a particularly harsh attack in 2009, which was leaked from an internal memo, Norway's deputy ambassador Mona Juul labelled him a "powerless observer" during that year's civil war in Sri Lanka, when thousands of civilians were killed as the army moved in to defeat Tamil Tiger rebels.

Ban Ki-moon has been criticised for being deferential to China

"The same qualities that have guaranteed re-election - inoffensiveness - have bitterly disappointed people who most believe in the institution," says James Traub, a freelance author who writes about the UN for New York Times Magazine and other publications.

"There are moments when you need the secretary general to be leader of public opinion, and he didn't do so, because he's more comfortable working in private."

However, Mr Ban, who has vigorously defended his record as making no "distinction or difference" when it comes to universal human rights, has been more assertive in the past six months.

He won praise for taking a firm line on election results in the Ivory Coast that saw the defeated incumbent Laurent Gbago ultimately forced from power. And he has spoken out in support of Arab pro-democracy protesters, publicly admonishing their leaders to listen to the voice of the people.

At the end of the day, secretaries general are defined by the events that take place during their tenure, which are caused mostly by member states outside their control. But James Traub says maybe 20% of the UN's status can be shaped by a dynamic leader.

"Kofi Annan, by virtue of who he was and what he said, was able to make the UN a more important-feeling place," says Mr Traub, "and I think people around the UN would say that Ban, by who he is and what he says, has made the UN a less important-feeling place."

Mr Lynch, however, compares Mr Ban to another secretary general, the Peruvian diplomat Javier Perez de Cuellar, who held the post for a decade until 1992. Like Ban Ki-moon, he was derided for back-room diplomacy during his first term, but oversaw seminal world events in his second.

"I think Ban could shine in a second term," says Mr Lynch. "I think he showed a little feistiness over his approach to the Middle East, and maybe he'll feel more independent than he does now, but I think he would need to think seriously about who he selects to help him through the next term."