Womb for rent: A tale of two mothers

- Published

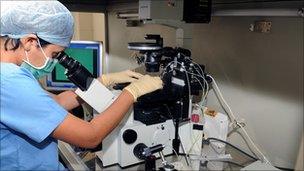

Surrogate mothers in the Akshanka clinic in Anand, Gujarat

The high cost of surrogacy in Europe and the US means many Western women are outsourcing pregnancy abroad. Carolina, from Ireland, travelled to India to pay Sonal to carry her baby. The World Service's Your World followed the two women as they came to terms with the emotional costs of the surrogacy.

Sonal, 26, has just given birth to a child she will never see.

"They took away the baby as soon as she was born," she says.

"I was unconscious when she was born so I didn't even see her. When I woke up, I asked my mother what had happened, she told me it was a girl."

Sonal, from the western province of Gujarat, has spent the past few months in the Akshanka clinic in the small town of Anand, away from her husband and young son and daughter.

Her husband is a vegetable vendor, earning up to 1,500 rupees (£21; $34) a month and his meagre salary is not enough to pay for the education she wants to give her children.

This is her second surrogate pregnancy, for which she will earn 300,000 rupees ($6,800; £4,200).

"I will be happy soon. I will have a house and I will live comfortably with my children. I will educate them," she says.

It is predicted that surrogacy will generate $2.3bn (£1.5bn) a year in India by 2012

The biological parents live 7,000km away in Ireland. At the age of 21, Carolina was diagnosed with cervical cancer and had her cervix removed. Although she was told she could still get pregnant, it would prove very difficult for her to carry a baby to full term.

"Even before I had cancer I wanted to have a baby," she says. "Anyone who knows me said I'm just meant to be a mother.

"Then when you have an illness and the chance is taken away from you, you spend the first few years thinking 'what am I going to do?' And before you know it, it's five years, it's 10 years, it's gone out of your life."

Social stigma

Surrogacy for material gain was legalised in India in 2002 but it is still a very controversial procedure.

When Sonal first told her husband that she wanted to take part in the surrogacy programme, he said he did not want her to do it.

"He said such things are not acceptable in our society," Sonal explains. "Finally, I convinced him.

"When I had my first surrogate baby, I fed her for three days, it felt as if it were my baby. When they took her away I cried for three days. I missed her so much.

"This time when I give my child to Carolina I will feel like I am giving my child to someone else, but later I will convince myself that it was her baby and I am giving it back. Once she is gone I will have to forget her."

Although Sonal's mother was supportive, the couple avoided telling her in-laws as they knew they would disapprove - for some Indians, carrying someone else's child is akin to adultery.

IVF specialist Dr Nayna Patel, who runs the Akshanka clinic, is aware of the criticisms of her practice but is keen to dispel the idea that the surrogates are exploited.

"When you see a baby in the hands of a couple who are infertile and have gone through so many treatments and you see the surrogate who was in rags and now has a house and can boast of educating her children... no amount of criticism is going to hurt you," she says.

Different expectations

The two women had maintained a good relationship throughout the pregnancy, with Carolina agreeing to buy a mobile phone for Sonal as well as some other gifts.

Doctors at the clinic counsel all those involved not to get too close, but when the baby was born, it was clear that Carolina and Sonal's expectations were different.

Due to complications, the newborn was immediately taken to a hospital ward across the street and Sonal was refused permission to breastfeed her.

Sonal was upset and confused. "I'm sad because I feel the efforts I have gone to for the past nine months have been a waste," she said.

"Carolina says that I cannot help her look after the baby, she will keep a nanny instead. I am really hurt."

When Carolina asked Sonal to send over breast milk for the baby, Sonal refused.

"I said if you can arrange someone to look after the child then you can arrange someone to feed the child as well. I asked her why should I send the milk from here. Why can't I live with my baby?"

For Carolina, the decision was wholly justified.

"Maybe in her culture that was the normal thing to do, to come and feed the baby and help me and be the nanny," she says. "But in my culture it would be different, I just felt that would be too close to home.

"I will always be eternally grateful to Sonal for what she has done, but I felt there has to be a cut off point."

Although Sonal was careful not to tell anyone where she had been, her in-laws found out about the surrogacy. She says that when she sees them, she will deny having been pregnant.

But as she comes to accept the loss of the baby she carried, she is defiant.

"I have no regrets, even if society casts me out or does not invite me in, I don't care. I am not doing a bad thing, I am doing this for my children," she says.

"I don't want anything else now, I just want my kids."

Your World is broadcast by the BBC World Service. Listen to this documentary here. Download the podcast.