Goran Hadzic arrest: A turning point for Serbia?

- Published

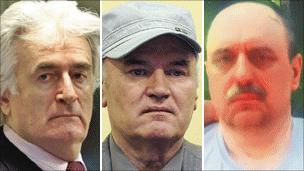

The failure to arrest these men was the biggest obstacle to Serbia's European Union membership

Each of the stories had its quirks.

With Radovan Karadzic, the former Bosnian Serb leader arrested in Belgrade in 2008, it was his elaborate double life as an alternative healer that would stick in people's minds: the long hair, heavy beard and false name.

Then came Ratko Mladic, commander of the Bosnian Serb army during the war.

He was said to have enjoyed local ham and cheese with the police officers who seized him in May this year, later requesting raspberries and Tolstoy novels in his Belgrade prison cell.

And now Goran Hadzic - one-time leader of the Croatian Serbs and, until his arrest on Wednesday, the last remaining fugitive of 161 suspects indicted by the UN war crimes tribunal in the Hague.

It was a stolen painting by the artist Amadeo Modigliani which reportedly led the security services to him. He had tried to sell it to finance his fugitive lifestyle.

The eccentricities made for striking headlines, but for Serbia these men - and the other former fugitives arrested here - represented something far more serious.

In their indictments, the horrors of the Yugoslav wars were laid bare: murder, torture, rape, genocide in the case of Karadzic and Mladic, and that legal euphemism "a joint criminal enterprise to expel the non-Serb population": ethnic cleansing.

For today's Serbia, trying to reinvent its past image as a pariah state, these men were a throwback to the bloodletting of the 1990s.

Accession talks

The failure to arrest them was the biggest obstacle to Serbia's hopes of eventual European Union membership.

And so the capture of the final man, Goran Hadzic, and the bigger fish before him, is of extraordinary importance to Serbia, to the victims of the Yugoslav wars and to the stability of the Western Balkans - still the most fragile corner of Europe.

It will allow Serbia to take a big step towards the EU later this year, when the country is expected to be given candidate status for membership and probably a start date for accession talks.

"I will look my European counterparts in the eye and see if they make good on what they have promised", said the Serbian President, Boris Tadic.

And it "ends a hard chapter of our country", he added, aiding reconciliation.

But war crimes analyst Dejan Anastasijevic urges caution.

"Reconciliation is a lengthy process and there are still many issues burdening the relationship between Serbia and Croatia, for example," he says.

"It's premature to declare that the past is behind us - it has a habit of jumping up and grabbing us by the throat when we least expect it.

"The arrest of the final fugitives will help Serbia to turn a new leaf but not to close the book entirely."

Enlargement fatigue

The road to Brussels will be tough for Serbia.

Nobody expects the country to join before 2020, as rooting out corruption and reforming everything from farming to the judiciary will take years.

The economic crisis has prompted a severe bout of enlargement fatigue within the bloc.

And there is still the major problem of Kosovo - Serbia's former southern province, whose independence Belgrade rejects.

A modus vivendi will have to be found before membership.

But resolving the fugitive issue was the priority.

"The failure to arrest them was used as an excuse by some EU countries not wanting to see Serbia's membership - now that's been removed," says Mr Anastasijevic.

The reaction from Europe to the arrest of Hadzic was indeed overwhelmingly positive.

"We salute the determination and commitment of Serbia's leadership in this effort," read a joint European Commission statement, calling it "another important step towards Serbia fulfilling its European ambitions".

Historical 'facts'

But what of ordinary Serbs?

There was a protest after Ratko Mladic was caught back in May - he still has a following among hardline nationalists.

But with Goran Hadzic, most have simply shrugged their shoulders. He was far less known here.

In fact, when it comes to the thorny issue of the past, Serbia is utterly divided.

Many Serbs believe their portrayal in the history books is unjust, that the West chose Serbia as the enemy and that joining the EU would betray the national interest.

Some are looking to sports stars like Novak Djokovic to be the new faces of Serbia

But the other side - just as large - is desperate to move on.

They crave a European future and want their country associated not with war crime suspects, but with representatives of the new Serbia, like tennis star Novak Djokovic.

And that chasm within public opinion is unlikely to narrow with the arrest of the final fugitive.

For each side in this region sees itself as the victim and each has its own truth.

Serbs, Croats and others will always argue over the "facts" of history.

National pride will always remain a strong force in the Balkans and sometimes an impediment to change.

But these countries are now gradually learning to live side-by-side, despite the differences and tensions.

The relationship between the governments and ordinary citizens is improving.

The hindrance to all of this has long been the war crimes suspects and what they symbolise.

Removing them from the equation will not change things overnight.

But now perhaps there can be less reason to dwell on the past for all these countries. And even that, in the Balkans, is progress.

- Published20 July 2011

- Published20 July 2011

- Published20 July 2011

- Published2 June 2011