Abe Lincoln and the 'sublime heroism' of British workers

- Published

Just off the vast expanse of Albert Square in Manchester is a smaller square named after an American president.

Unnoticed, for the most part, by post-pub revellers and shoppers, Abe himself towers above the scene in Lincoln Square, hatless, tousled hair flying and brow furrowed.

He is there because he wrote a letter to the people of Manchester. Well not the whole people.

One hundred and fifty years ago the people of Manchester were divided, over the same issues that had divided America: cotton, slavery and freedom.

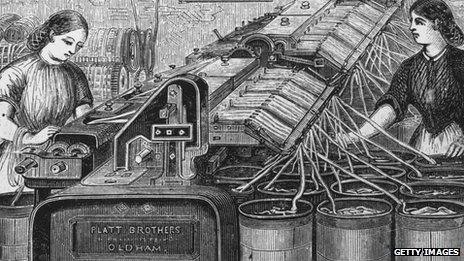

By the time the American Civil War started, in 1861, Lancashire was the "workshop of the world". Its 440,000 cotton workers, spinning and weaving in 2,400 factories, were as vital to the world economy as the Chinese region of Guangdong is today.

They had had a turbulent past: slaughtered at the mass demonstration of Peterloo, external in 1819, on general strike as recently as 1842, seized with Chartist, external discontent in the revolutionary year of 1848.

But they were calming down.

Cotton trade unions had emerged for which socialism - as the old firebrands lamented - had become merely a "bread and butter" issue, not a utopia. Wages had risen, calm had settled in.

But now, with the conflict in America, disaster struck.

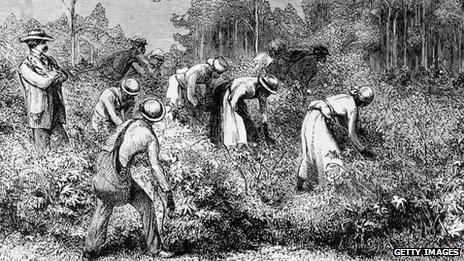

Lancashire's main source of cotton was the Confederate states: 1.1bn lb a year were being shipped into Liverpool, up various canals and railways, to be processed in the small coal and cotton towns of the region.

When the Union side imposed a naval blockade on the South, the main source of cotton dried up. Some factories were able to switch to lower grade cotton from Egypt or Asia, but many closed: the classic financial squeeze took place on businesses already leveraged to the hilt to take advantage of a boom.

Mills closed and were mothballed. Workers - despite enthusiastic charity efforts mobilised by local bigwigs - went without food and heating, or were evicted.

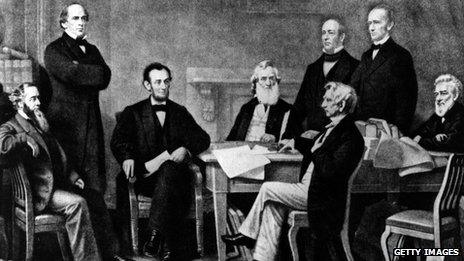

By the autumn of 1862-1863, just as in the United States Lincoln was issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, turning the American conflict into a full-blown fight with slavery, the town of Stalybridge had just five out of 39 cotton mills working, 7,000 unemployed and 750 empty houses.

The Emancipation Proclamation freed slaves in Confederate areas

When the charities ran out of money, and tried to pay people with food stamps the usual Lancashire response ensued: led by "women and girls" Stalybridge revolted.

"… The old performance was repeated. Provision shops entered, stones thrown and a great crowd collected," wrote the Special Correspondent of the Daily News. "People have nothing to do; everybody goes to see. Many watchers make a mob. And the spirit of mischief - especially where there is an Irish element of population - shoots through the crowd like an electric spark." (Thus proving that urban riots and the way they are reported in the press does not change much over 150 years)

The Hussars were called in, bayonets were fixed and order was restored.

Politically, Lancashire was already split. The shipping and finance bosses in Liverpool had openly sided with the Confederacy, and organised both warships for the South and blockade running merchant ships out of Merseyside.

Now clamour began among the mill owners for the British government to deploy the Royal Navy to break the Union blockade - effectively putting Britain on the side of the slave-owners' revolt.

This alliance of ship and mill owners was not shy about mobilising meetings in favour of British military intervention.

The 13th amendment to the constitution abolished slavery in the USA

The cotton workers' response was to organise a campaign of public meetings in support of both the blockade and the Union.

I can attest - because I am descended from them and have heard the folklore - that Lancashire cotton workers in the mid-19th Century were acutely aware, every day, that the last hands to touch the cotton before them had been black hands and unfree.

Their support for the Union was not some abstract principle, but an expression of human sympathy with millions of black Americans that defies the historical stereotype of 19th Century workers as an uneducated mob.

A speech by the liberal MP John Bright serves as a nice compare-and-contrast to today's standards of parliamentary language: "Privilege has shuddered at what might happen to old Europe if [America's] grand experiment should succeed," he told a mass meeting of trade unionists.

"I have faith in you. Impartial history will tell that, when your statesmen were hostile or coldly neutral, when many of your rich men were corrupt, when your press - which ought to have instructed and defended - was mainly written to betray, the fate of a Continent and of its vast population being in peril, you clung to freedom."

The old Chartist agitators now popped up. "Working men," veteran Chartist Ernest Jones told a demonstration in Ashton: "I say the South is your enemy - the enemy of your trade, the foe of your freedom, a standing threat to your property. Slave labour is direct aggression on the free labour of the world. The key that shall reopen our closed factories is the sword of the victorious North."

But this was essentially a civic movement - an alliance of workers and liberal politicians.

At a mass meeting in Manchester's Free Trade Hall, on New Year's Eve 1862, attended by a mixture of cotton workers, and the Manchester middle class, they passed a motion urging Lincoln to prosecute the war, abolish slavery and supporting the blockade - despite the fact that it was by now causing them to starve. The meeting convened despite an editorial in the Manchester Guardian advising people not to attend.

Mr Lincoln, in a letter dated 19 January 1863, 150 years ago on Saturday, replied with the words that are inscribed on his statue:

"I cannot but regard your decisive utterances on the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country.

"It is indeed an energetic and re-inspiring assurance of the inherent truth and of the ultimate and universal triumph of justice, humanity and freedom… Whatever misfortune may befall your country or my own, the peace and friendship which now exists between the two nations will be, as it shall be my desire to make them, perpetual."

The American Civil War, then, was a chapter in British social history, and the audiences for Speilberg's film, external, discovering the incredible radicalism and eloquence of President Lincoln are not the first Brits to be mesmerised en masse by the self-educated lawyer from Springfield, Illinois.

Maybe one day we will get a movie worthy of men like John Bright and Ernest Jones.

In 2007 Paul Mason told the story of the rise and fall of the cotton industry which shaped Lancashire in the Radio Four series Spinning Yarns.