The struggle to save Egypt's revolution

- Published

- comments

There was a time in Egypt when many hailed "one hand", one square, one people rising up to make their own history.

That one-ness is no more.

In Egypt today, a people pulls apart, two public spaces in Cairo are seething, and many hands are now said to be at work.

In the iconic Tahrir Square, where protesters played a key role in ousting President Hosni Mubarak in February 2011, "one hand" now includes the army which ousted the elected President Mohammed Morsi last week.

In this famous gathering space, green laser lights and fireworks are now on sale to celebrate what banners emphatically proclaim was "not a coup" but the biggest demonstration in Egypt's history to put democracy back on track.

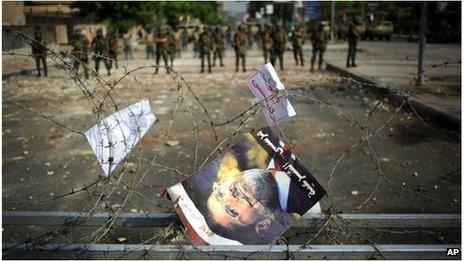

In eastern Cairo, in tented encampments plastered with Morsi photographs around the Rabaa al-Adawiya mosque, people are selling thick bamboo sticks which they insist are for self-defence against soldiers and police.

A widening array of makeshift stalls are also selling hot and cold drinks, hats for protection against a scorching sun, and food of all sorts to cater to a fast-growing community of protesters, mainly Muslim Brotherhood supporters, who say they are not leaving until their elected president is reinstated.

About a kilometre away, there is a tense stand-off around the Republican Guard Officers' Club. More than 50 people were killed and hundreds injured there on Monday, when soldiers and police opened fire at dawn just before morning prayers.

There is no agreement on what happened there either.

Army spokesman Col Ahmed Ali told a news conference that security forces had no choice but to open fire. "We had to respond," he insisted, giving details of "snipers behind buildings" and "armed groups attacking the area" as well as security forces.

Dialogue 'impossible'

When that press conference was being broadcast live on Egyptian and international media, the large crowds milling around the Rabaa al-Adawiya mosque chanting angry slogans against a "massacre" did not pay attention.

The BBC's Lyse Doucet in Nasr City: "Protesters say they are not going anywhere until Mohammed Morsi is reinstated"

I asked a spokesman for what is called the Legitimacy Coalition, Ahmad al-Nashar, whether they would consider this detailed account by the security forces.

"Definitely not," he declared. "We were there. We have our own films that show they opened fire on civilians who were praying."

In a sense, what matters most now is not what happened but what people believe. It is what drives a deepening sense of anger and injustice in two rival camps.

And the battles over what should happen next are just as difficult, and dangerous.

Talks behind closed doors also suffered a major setback with this latest violence. The Salafist Nour party, the second largest Islamist force, also condemned "a massacre" and pulled out of protracted negotiations over a new caretaker prime minister and cabinet.

The presence of Islamists alongside an array of more liberal forces had strengthened the argument that this was a popular move against an increasingly unpopular president.

Calls for reconciliation are echoing in a flurry of statements, everywhere from the army, to the liberal National Salvation Front, to the influential Al-Azhar mosque.

But Muslim Brotherhood spokesman Gehad al-Haddad, one of its few leading members who has not been detained, told the BBC dialogue was impossible while Mohammad Morsi was detained, and deposed.

'He failed us'

There was never a true meeting of minds among the diverse forces who came together to end decades of authoritarian rule in 2011. Now, even meetings seem impossible.

There is a struggle to claim the mantle of a revolution that has made for awkward bedfellows.

In Tahrir Square this week, I saw two policemen in sparkling white uniforms, smiling and at ease, in the front row next to the stage where nationalistic songs were blasting from speakers.

That would have been unthinkable in 2011 when the police were widely reviled, and forced to retreat, even from the streets.

And there are also warnings of counter-revolution too with elements of the former Mubarak regime accused of cloaking themselves in the symbols of the revolution to return to their power and privileges.

"It's a public space so it can be used by anyone," remarked Egyptian journalist and author of Liberation Square Ashraf Khalil, as we stood on the edge of a huge exuberant crowd.

But in Tahrir I also met Egyptians who had come to the square for the very first time because they felt so strongly that Mohammed Morsi's rule had betrayed any hope for democracy in Egypt.

"I came to help my country Egypt," Amr, a lecturer and veterinarian told me.

The military has been trailing the colours of the Egyptian flag through the skies of the capital

His friend next to him, who voted for Mohammed Morsi, chimed in: "He failed us. I came here to support the revolution."

But it is not just the revolution which is now in danger.

In an interview just hours before this latest tragic shooting, Hossam Bahgat, director of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, was already emphasising that "the most pressing concern for us is for violence to stop, order to be restored, and for security forces to avoid excessive use of force".

But now the Muslim Brotherhood publicly calls for Egyptians to rise up "against those trying to steal their revolution with tanks", and there are dark warnings of vigilante groups, criminal mobs, and more extreme Islamist groupings who never truly trusted the slogan "democracy is the answer".

In the midst of the mounting tension, there is still one thing which unites all squares, and most forces. Wherever crowds gather, a human canvas is dotted with Egypt's distinctive tricolour flag.

Egypt's air force has been flying the flag too - literally. Plumes of red, black and white smoke have been streaking from jets screeching across the skies above Tahrir and Rabaa al-Adawiya mosque.

But as a people pull apart, fear grows not just about saving a revolution, but a country too.