Mexico and marijuana: A leaf out of Uruguay's book?

- Published

Ten days ago, the lower house of Uruguay's parliament passed a law legalising marijuana, reflecting a growing sentiment in Latin America that the current prohibition on drugs should change. Could Mexico be next?

Arguably, Mexico has lost the most in the war on drugs, with tens of thousands of drug-related killings every year. But there are now calls for Mexico to take a leaf out of Uruguay's book and pass similar legislation.

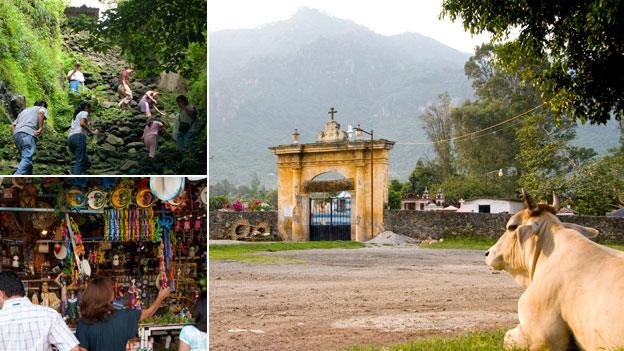

Tepoztlan is known as a pueblo magico, a magic village. Rugged, jungle-covered mountains ring a small Jesuit conurbation of colonial cobbled streets. At the summit of one of the peaks, a pre-Hispanic temple, Tepozteco, looms above the village, as both guardian and deity, lending a further sense of mysticism to the place.

As such, Tepoztlan is a popular destination for young hipsters and ageing hippies alike. At night, the mezcal flows, and in the more tolerant bars, the unmistakeable wafts of pungent marijuana smoke billow across the customers as jazz-fusion or ambient bands play on stage. The vibe is mellow, to say the least.

And if Vicente Fox gets his way, it could become the norm. He wants the bar owner to be allowed to offer you two menus when you come in, one for alcohol, the other for grass.

"Of course, you must enforce the law," the towering six-foot-something former Coca Cola executive told me last year. "But we need other strategies. One, which I am promoting, is legalising the consumption, production and distribution of all drugs."

Vicente Fox, lest we forget, was Mexico's president between 2000 and 2006. The first president to break 71 years of uninterrupted rule by the Institutional Revolutionary Party or PRI. The man who arguably launched the drug war, as the violence began to turn up several notches towards the end of his time in office.

Now he argues: "We must take away the mammoth amount of money the criminals are getting from this income especially from the market in the United States, the largest drug consumer in the world."

That was last year, with weeks to go before the presidential election which saw his party ousted from office and replaced once again by the PRI.

This year, he went a step further, organising a forum at his ranch in Guanajuato, on the rights and wrongs of drug legalisation. Among the keynote speakers was Jamen Shively, an ex-Microsoft executive who is trying to set up the world's first commercial marijuana brand.

One of the speakers at Mr Fox's forum was Jamen Shively (L), who wants to set up a commercial marijuana brand

For the first time, there is an industry worth up to $100m a year, and yet "no established brand name exists," he told the assembled experts and journalists with disbelief.

A former manager of Microsoft sitting on a stage next to a former executive of Coca Cola, both extolling the virtues of drug legalisation. Clearly there is money to be made in creating the world's first legal Marijuana Incorporated Company.

Mr Fox's new position on drugs is a U-turn of epic proportions. This was his take on the issue in the year 2000: "We must be against the consumption of drugs in Mexico," he said as presidential candidate. "We should change the law so it's clear we're against the consumption of drugs... There should be an initiative in place to punish drug consumption."

Actually, in Mexico itself, the drug laws are surprisingly liberal. Since 2009 it is legal to possess up to 5g of cannabis, 2g of opiates, 0.5g of cocaine and even 50mg of heroin for personal use.

But nevertheless, the debate rages on. Every day, it seems another high-profile politician in the region comes out in favour of change, whether it's decriminalisation or complete legalisation. Just to voice such ideas as a sitting president 10 years ago would have brought down the ire of the White House upon you, let alone to push legislation through parliament, like Jose Mujica in Uruguay.

There is one well-known Latin American who remains unconvinced, though. Pope Francis, an Argentinian, recently attended the inauguration of a drug rehab clinic in Rio de Janeiro. In his first public address on the issue, he let the world know in no uncertain terms where he stood on the question of legalisation.

"A reduction in the spread and influence of drug addiction will not be achieved by a liberalisation of drug use, as is currently being proposed in various parts of Latin America," the pontiff said.

To be honest, his comments are unlikely to concern the young people of Tepoztlan, who are far more likely to listen to the former left-wing guerrilla, President Jose Mujica in Uruguay, than the Pope.

"Mi medicina" or "My medicine," one of the dreadlocked musicians grinned at me, as she lit her post-gig joint backstage. Soon, she may even be able to buy it at the pharmacy.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external