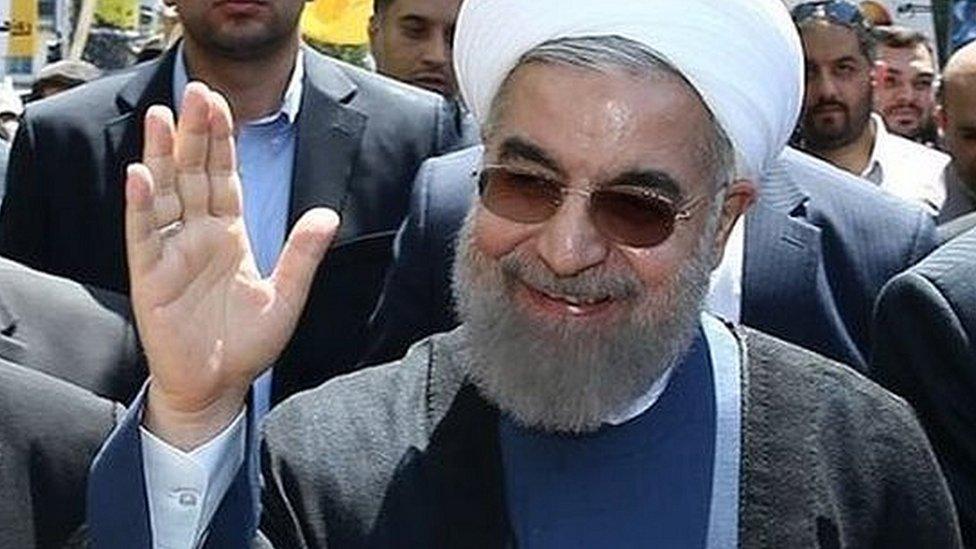

Has Iran's President Rouhani wrong-footed the West?

- Published

Many in the US still distrust Iran

Iran's new diplomacy has rattled many in the foreign policy establishments of the US, Britain, and France.

After President Hassan Rouhani's appearance at the United Nations general assembly last month and pledge "to discard any extreme approach in the conduct of our relations with other states", a wave of public expectation has led officials on both sides of the Atlantic to wonder how they might regain the initiative or at the very least avoid blame if little comes of it.

President Rouhani has pledged to resolve the nuclear issue in the next six-12 months. This sense of urgency causes further unease among seasoned British or American Iran hands both because it further raises hopes and may suggest that President Rouhani has been given a limited window by Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei to resolve the issue.

The closest anyone has come to explicit party pooping is when John Kerry, the US Secretary of State, pointed out on Monday while visiting Indonesia, that Iran had still not formally responded to proposed terms that had been offered during talks in February and that the US was "waiting for the fullness of the Iranian difference in their approach" to show itself.

UK Foreign Secretary William Hague meanwhile, in an attempt to steal a march on Tehran, on Tuesday announced the nomination of an official to work towards the reopening of diplomatic relations.

Among the US arms control policy in-crowd, concerns multiplied about the new Iranian president's willingness to compromise its nuclear ambitions following a session at New York's Council on Foreign Relations think tank on 27 September.

Coming shortly after the meeting between Mr Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohamed Javad Zarif, the first such encounter for more than six years, nobody wanted to sound the wrong note during the session.

However someone who was present during the informal part following the on-the-record remarks, says: "The impression we got was that President Rouhani would regard the giving up of even one of their 18,000 [uranium enrichment] centrifuges as an unbearable blow to national pride."

Mr Zarif later said, on the record, that Iran regarded its right to enrich the nuclear fuel as "non-negotiable".

The Americans were thus left less impressed with the new Iranian team's fresh approach than the public celebration of President Rouhani's phone call with US President Barack Obama or the Kerry-Zarif meeting might have suggested.

But was the position privately articulated in New York, of a reluctance to accept any compromise to its enrichment activities simply the opening position in a negotiation? All eyes will be on Geneva next week, where substantive talks with Iran on its nuclear programme are due to take place.

President Rouhani has promised to resolve the nuclear issue in the next 12 months

Concerns that the Iranians may be taking a very tough negotiating stance mean that while Iran's foreign minister will be going to Geneva, Mr Kerry and Mr Hague will send senior officials.

Russia's Sergei Lavrov, whose appetite for Western diplomatic squirming has apparently been sharpened rather than sated by recent developments over Syria, is thought not to be attending either. While the New York session last month saw the foreign ministers presiding in person, the UK and US in particular do not want to turn up and create an expectation of breakthrough when, as Mr Kerry pointed out, they have not yet seen evidence of change in Iran's substantive position.

Perhaps they will "reward" the Iranians with the full ministerial treatment once there is something of substance to declare.

Western unease is also clear on the matter of that other Geneva meeting - the one that is meant to be happening in November to start some sort of peace process between Syria's warring factions. The so-called Geneva II conference was mooted back in May but has failed to materialise for many reasons.

Among the vexed Geneva II issues, are whether Iran should attend.

Britain has publicly opposed this in the past, but in the run-up to the G8 summit in Northern Ireland, people in Whitehall started to use vaguer language.

On Tuesday one official said Iran could attend "so long as it shares the values of Geneva", ie that the talks will produce a process of transition, in which President Bashar al-Assad's government leaves power.

However the same British official then lambasted them, noting: "Iran has become more directly militarily engaged on the ground… in sizeable numbers at times."

If Iran attends, then the Syrian National Coalition opposition bloc has threatened to pull out.

If it is not part of the putative peace process, will Iran undermine it? This is the dilemma facing Western diplomats.

On both the nuclear issue, and Syria the next few weeks will be vital in terms of judging the new Iranian approach to foreign policy.

The US and other Western countries will have to ask themselves difficult questions - just how much can the Iranian nuclear programme be set back since a complete halt to uranium enrichment in the country now seems out of the question?

And given the experience over the chemical weapons issue, is a Syrian peace conference in which Russia and Iran play an important part worth reaching for, even if that makes it unlikely that a broad range of opposition groups would attend?

- Published20 May 2017