Profile: Hassan Rouhani, President of Iran

- Published

Hassan Rouhani came to power promising to end Iran's diplomatic isolation

For a president who began his first term in the centre of the Islamic political spectrum, Hassan Fereydoun Rouhani, 68, has now moved firmly to the left, placing himself with the reformists.

In his election campaign for a second term in office, he promised a moderate modern and outward looking Iran, in sharp contrast to the vision his main rival Ebrahim Raisi, a hardline senior cleric and judge, had put forward.

He warned Iranians that a single wrong decision by the future president could engulf the country in war. This was a reference to Mr Raisi, who is not overly impressed by the nuclear deal President Rouhani reached with world powers - a deal which removed a serious threat of war hanging over the country.

President Rouhani is keen to see the nuclear deal survive - even though US President Donald Trump and opponents of the deal in the United States Congress are looking for ways to put further pressure on Iran, or even scrap the deal.

Mr Rouhani also promised to revive the sluggish economy, to extend individual and political freedoms, to steer the country away from the extremist ideas of the hardliners, to ensure equality for men and women, to extend access to internet and generally work for moderations and an outward-looking Iran.

Time and again, he praised the reform movement in Iran and its leaders - something that is likely to bring him into constant clashes with the hardliners in his second term. He was re-elected in May 2017 with an emphatic margin of victory.

Nuclear negotiator

Hassan Rouhani has been a key player in Iran's political life since the revolution in 1979.

He was an influential figure in Iran's defence establishment during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War and subsequently held several important political posts.

From 1989 to 2005, Mr Rouhani was secretary of the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC), the top decision-making body in Iran, appointed by and answerable to the Supreme Leader.

There was a lowering of political tension between Iran and the US under Mr Rouhani - here his foreign minister chats with his US counterpart

He served as deputy speaker of parliament between 1996 and 2000 (while simultaneously completing a thesis on Sharia - Islamic law - as a post-graduate student at Glasgow Caledonian University) and in 1997 became a member of the Expediency Council, the highest arbitration body on issues of legislation.

Mr Rouhani was Iran's chief nuclear negotiator, from 2003 to 2005, earning the moniker "the diplomat sheikh", when he agreed to suspend uranium enrichment.

He resigned from the SNSC and from his role leading the nuclear talks just weeks after the election of the combative Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, amid sharp differences with the new president.

First Term

When Mr Rouhani stood as a presidential candidate in 2013, he knew he was up against an establishment stacked with hardliners who were highly suspicious of him.

His campaign slogan "moderation and prudence" resonated with many Iranians who had seen their living standards, and their country's reputation, plummet under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Although he was seen as part of the establishment, Mr Rouhani promised to relieve sanctions, improve civil rights and restore "the dignity of the nation" - and drew large crowds on the campaign trail.

Hassan Rouhani (right) replaced Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (left), though is not thought to have been the Supreme Leader's first choice

Many believe he was not the first choice of the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. But seeing that he might offer a way to end the nuclear confrontation with big world powers without destabilising the whole system, Mr Khamenei backed Mr Rouhani.

Within weeks of taking office in 2013, Mr Rouhani spoke on the phone to US President Barack Obama - the first direct contact at the highest level between Iran and the US since the 1979 revolution.

The conversation paved the way for historic open and direct talks between Iran and the US, as well as with other world powers.

After assuming office himself in 2013, Mr Rouhani got the Supreme Leader to allow the foreign ministry, rather than the SNSC, to take charge of nuclear negotiations with the West, and appointed his Foreign Minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, to lead the talks.

The sight of Mr Zarif and US Secretary of State John Kerry taking a stroll around Lake Geneva just outside the venue of nuclear talks, chatting and joking together, would once have seemed extraordinary.

But as the negotiations progressed, it became almost commonplace.

Challenges ahead

From the outset Mr Rouhani had cautioned that there would be "no overnight solutions" to Iran's many problems.

The nuclear deal ensured that many sanctions against Iran were lifted, but the benefits of this have been slow in coming for many Iranians. Ordinary Iranians say they have not felt it in their day-to-day lives. The economy remains sluggish, and desperately needed foreign investment has been far slower than had been expected.

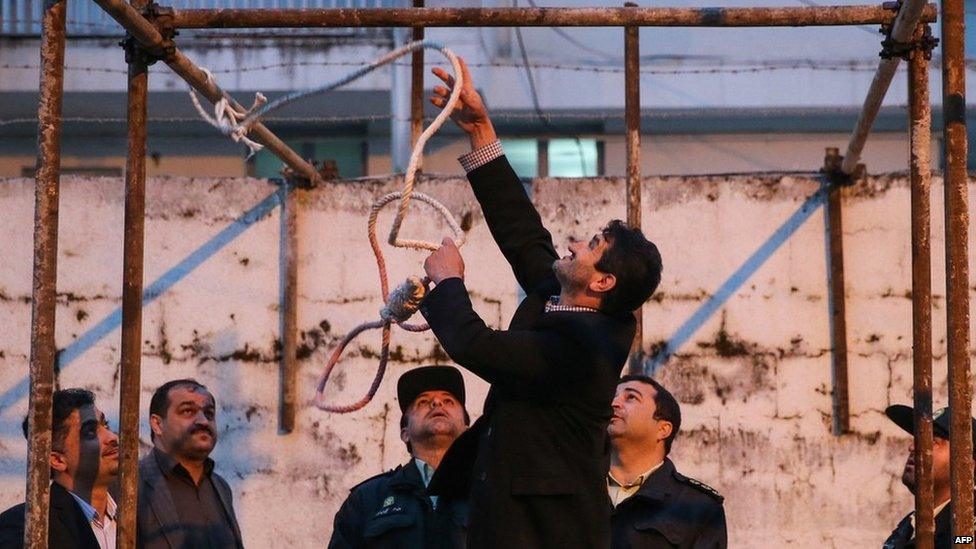

Iran's poor human rights record is routinely condemned by campaign groups and countries including the US

Mr Rouhani had pledged to help free reformist opposition leaders, held without trial since 2011, but the hardliners have stood firm and they remain under house arrest.

He also promised to usher in an era of more freedoms in a country where human rights abuses are rife. However, few believe there has been much improvement here, and in some areas the situation may have worsened.

There are still many journalists and opposition activists in jail, and the number of executions carried out in Iran has soared.

Censorship in the media has not eased under Mr Rouhani, although in one of his key speeches as president he told state media chiefs that Islam could tolerate a lot more than state TV allows its viewers.

Iran's internet also remains tightly controlled, forcing many to use proxy servers to circumvent the restrictions in a country whose internet speeds rank among the lowest in the world.