Hard news for Turkey's journalists

- Published

Investigative journalist Ahmet Sik was injured twice while covering the protests in Istanbul last summer

"The police were just behind us. The first tear gas they threw hit me. I clutched my head. Blood was pouring out."

Ahmet Sik is a widely respected, well-known investigative journalist in Turkey. He recalls the day he got injured while covering the protests in Istanbul's Gezi Park this summer. He is convinced that he was targeted by the police.

"There were at most 10 metres between us," he says.

"A gas bomb that's thrown by hand hits me directly on the head. The people who were hospitalised just after me were: a pro-Kurdish opposition MP, a main opposition MP and the journalist who took the iconic picture of a woman in red dress being tear-gassed. This can't all be coincidence."

More than 100 journalists were injured while covering the Gezi protests.

But although some journalists were - against all odds - trying to report on the protests, the mainstream Turkish media initially avoided covering them.

This fuelled the suspicion of protesters that the media had either been ordered by the government to look the other way, or were doing so out of fear or favour.

Ahmet Sik believes the media blackout actually fuelled the protests. "If those people [protesters] could have heard their voices on television, I do not think these protests would have got this big," he says.

Turkey's Union of Journalists say more than 100 journalists were injured while covering Gezi Park protests

I approached several media bosses for comment. None of them was willing to talk.

The Turkish government denies any press censorship. Instead, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan has blamed the foreign media for misrepresenting Turkey.

Rape threats

I had been sent by the BBC from London to cover the protests in Istanbul and I tweeted a comment from one protester calling for an economic boycott for six months to get the government to listen.

Later, the quote was ascribed to me by the mayor of the Turkish capital, Ankara, as if I had had been the one calling for a boycott.

He started a Twitter campaign against me, calling me a British agent and a traitor and called on his more than 700,000 followers to show their "democratic reaction". Thousands of death and rape threats followed.

Two days later, Mr Erdogan accused me in a speech of "being involved in a conspiracy against my own country".

The threats and the hate campaign against me have fizzled out but, months later, some journalists in Turkey are still being intimidated by officials.

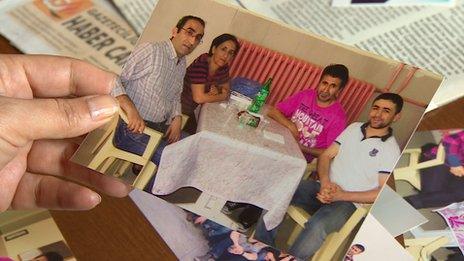

The BBC’s Selin Girit spoke to Ali Ismail's mother and father

Relentless reporting

Ismail Saymaz, an investigative journalist, has been covering the death of 19-year-old Ali Ismail Korkmaz, who was allegedly killed by the police during last summer's protests.

He was the first journalist to publish the CCTV footage showing how Mr Korkmaz was kicked severely in the head.

After investigating this story, Saymaz received an email from the governor of Eskisehir, the city where the attack took place.

The email, sent at four in the morning, began: "My son, you are being naughty again."

"He used insults like you're 'vile' and 'dishonourable' and made references to death," Saymaz recalls.

"I did not get nervous," he tells me. "Actually I am used to public officials complaining about me. I was surprised, though. Intimidation through an email? I've never seen that before."

In Antakya, a border town with Syria, Mr Korkmaz's close-knit family is still grieving over the loss of their beloved son.

His brother Gurkan takes me to his room which now feels like a shrine in memory of the boy: his colourful t-shirts laid gently on his bed, his photographs attached to the walls, newspaper clips about his death everywhere.

They are grateful to journalists like Saymaz who have reported on his death relentlessly.

Gurkan Korkmaz says: "At first, the governor said, Ali might have been beaten up by his friends. Then he said, 'the Turkish police would never do such a thing'.

"If the media had not pursued it, this case would probably have ended with, 'his friends beat him up'."

The trial of suspects in the death of Ali Ismail Korkmaz is expected to start in February.

Saymaz is determined to continue reporting the story "because maybe this story will prevent another young person being killed in the same way, at least in Eskisehir".

"It might prevent another public official treating another journalist as if he was under his command," he says.

"If there is a better country to be built tomorrow, these stories might be amongst the many small bricks in its construction."

The governor of Eskisehir was not available for comment.

Jailed journalists

Journalists are physically safer today than in the 1990s, when the Kurdish conflict was in its most intense phase, but critics say they do not know when or why they might be prosecuted or jailed now.

Turkey's Journalists Union says there are 60 journalists still imprisoned in Turkey, which makes it the biggest jailer of journalists.

Two prominent Turkish journalists discuss the limits to press freedom in Turkey

Recently, seven journalists received life sentences, not for their journalism, the judges say, but for terrorism.

Sweeping anti-terror laws, critics say, are used like a dragnet, catching anyone straying too close to the red lines in Turkish politics.

In Istanbul, I met the sister of one imprisoned journalist, Huseyin Deniz, Berlin correspondent for a leftist Turkish newspaper who once edited a pro-Kurdish paper.

For Dilsah Deniz, the charge that her brother is a member of a terrorist organisation is "ridiculous".

"Terrorist acts should be things related to violence," she tells me. "Writing or talking about the Kurdish issue is not terrorism."

Dilsah tells me she can visit her brother Huseyin (third from L) once every month. He's been imprisoned for the last two years

Turkey's Union of Journalists says that in the last few months more than 200 journalists have been sacked or forced to resign for covering issues the government finds sensitive. There also appears to be a creeping culture of self-censorship.

I have made repeated requests to the government for interviews but no-one was available for comment. Several pro-government journalists who say there is no crackdown on press freedom in Turkey declined my requests as well.

Communications professor Yasemin Inceoglu says that both the pro-government and the opposition media in Turkey work as propaganda tools, polarising society.

"When somebody criticises the government, they must not treat him or her as a traitor in Turkey," she argues. "When you criticise, they think you are supporting a coup or trying to overthrow them. That perception must change."

Now the Turkish prime minister is facing what many say is his greatest challenge yet, this time coming from a former ally.

A controversial Islamic cleric, Fethullah Gulen, is said to have extensive influence over the judiciary and police force. He has turned against the government, amid widespread allegations of official corruption amounting to billions of dollars.

Mr Erdogan's response has been typically forthright. He said: "I'm appealing to the judiciary. You cleanse yourselves too. I'm appealing to the businessmen. You will be the ones who lose. I'm appealing to the media. You will be the ones who lose. Because you're not honest. You are slandering our government with lies and trying to weaken it."

No one can predict the outcome of this conflict. But the way it unfolds and how it is portrayed in the media could have a long-lasting impact on Turkish democracy.

You can hear and see more about this topic at these times on BBC World TV on Tues 24 December: 0230, 1330, 1930, 2330 GMT, and on BBC News Channel at 1230 and 2130 GMT on 29 December or catch up later on BBC iPlayer.