How do you verify a militant's death?

- Published

If confirmed, Belmokhtar won't be the first person to be taken or killed by US forces in Libya

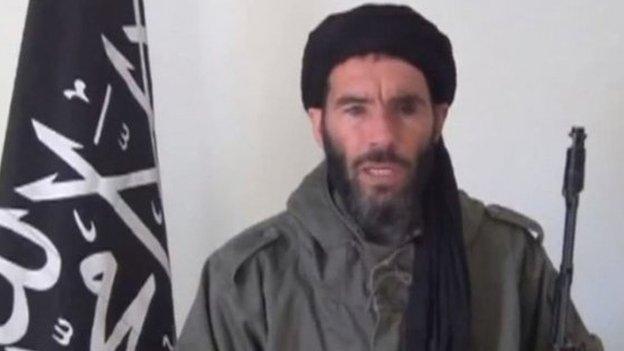

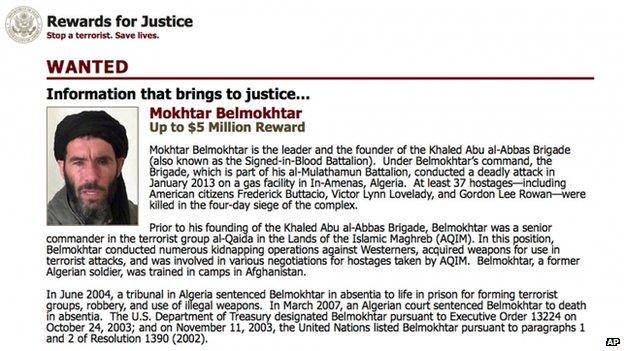

Like a cat with nine lives, militant Mokhtar Belmokhtar - dubbed "the uncatchable" - has been reported dead at least three times in recent years. Official confirmation of the latest reports of his "killing" is yet to come from the US, but how exactly do governments and their militaries go about verifying militant IDs after the kill?

Tobias Borck, an analyst with the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (Rusi), says verification of a kill depends on the type of operation carried out in the first place.

He contrasts the air strikes targeting Mokhtar Belmokhtar to the operation carried out by US special forces to kill Osama Bin Laden four years ago.

"One was killed from the air, the other was killed by soldiers going in in person. The latter is obviously much easier for identification purposes," Mr Borck says.

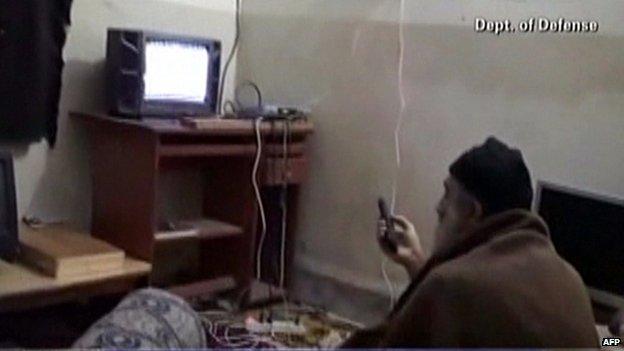

Bin Laden was shot in a night-time raid at his compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, in 2011. His body was transported to a ship for DNA tests before being dropped into the Arabian Sea.

Intelligence gathering

"Because physical verification of ID - like DNA testing - cannot be done from the air, one has to rely on other information, in particular intelligence gathered both before and after the strike," Mr Borck adds.

"To put it crudely, if you drop a missile on someone, there won't be much left of them," he adds, "but, in terms of 100% certainty, you will only get this if you do a Bin Laden operation and go in."

But in most cases, where getting a visual ID is not possible, DNA testing after the event is the preferred method of choice.

Videos of Osama Bin Laden were found after the US raid on his Pakistan compound in 2011

Matthew Henman, head of Jane's Terrorism and Insurgency Centre, says the authorities rely on DNA testing, especially after air strikes when there may not be sufficient remains to identify a corpse by sight.

This happened in the case of one of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb's (AQIM) most feared and radical commanders, Abdelhamid Abou Zeid, who was killed in fighting in early 2013.

Algerian TV first reported the killing at the end of February. This was corroborated by Chadian President Idriss Deby, who said his troops had killed the militant in battle in the mountains of northern Mali.

His death, however, was not officially confirmed until France formally identified Abou Zeid through DNA samples, almost a month later.

But DNA testing has also been used for 100% verification, even when there is an identifiable body, as was the case with the killing of Osama Bin Laden, says Mr Henman.

Martyrdom or death notices

In the event a body cannot be recovered and there are no means of formal ID, most governments wait for official confirmation from the militant group itself - often a long process.

Militant groups need time to reorganise and work out who will be the successor before issuing a martyrdom notice, says Matthew Henman.

How long this takes depends on the organisation and media abilities of the group, he says.

"For big groups like the Taliban and Islamic State, which are media-savvy and well-structured, a formalised death notice can be put together quite quickly.

Belmokhtar, left, has resurfaced many times after his death was announced

"But for AQIM, which can be quite disparate and disorganised, they often send video statements to Mauritanian news agency Al-Akhbar and this may take several weeks."

Even if a militant group announces the death of a leading figure, Mr Henman warns "there are obvious trust and verification issues".

It might be in a group's interest to say a leader has died when actually the man in question is continuing to operate behind the scenes but it is a sneaky practice which is not often seen, he adds.

Meanwhile, Rusi's Tobias Borck says there is very little reason to doubt a militant group's death announcement.

"However, if a group says its leader hasn't been killed, then we should take it with a pinch of salt".

There are constant issues with verification, and until there is proper confirmation, analysts say many people just won't believe it.

Counterterrorism cooperation

The operation against Belmokhtar was not the first time the US had entered Libyan territory or air space to carry out a counterterrorism operation.

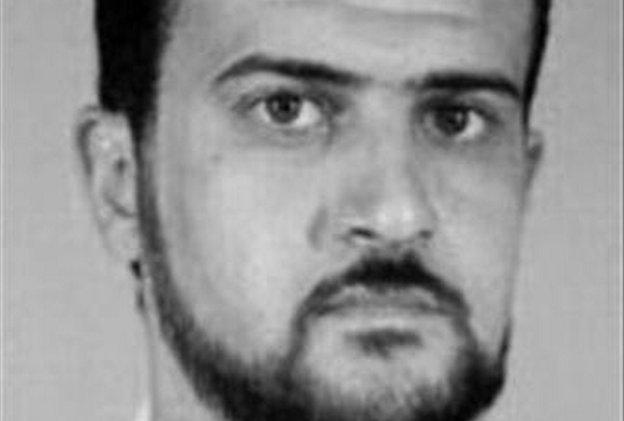

Anas al-Liby, one of the masterminds behind the US embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, was captured in a raid by US commandos in Tripoli on 5 October 2013.

The US forces and the internationally-recognised Libyan government also launched a combined operation to arrest Ahmed Al Khattala in June last year. He was one of the suspected ringleaders of the 2012 terrorist attacks in Benghazi that killed four Americans, including US ambassador Chris Stevens.

Al-Liby was charged with involvement in one of al-Qaeda's worst attacks in Kenya and Tanzania

"I imagine the US is doing whatever it can to partner with the Libyan authorities to get verification of Belmokhtar's death," says Matthew Henman.

Mr Borck agrees that verification can be difficult without having people on the ground. The CIA and other Western intelligence agencies are likely to have local networks in Libya working with them to help verify the reports, he says.

"In a situation like this, proper verification will be done by corroboration with different sources on the ground to confirm Belmokhtar was in the house at the time of the strike."

- Published15 June 2015