No easy answer for Syria's dispossessed

- Published

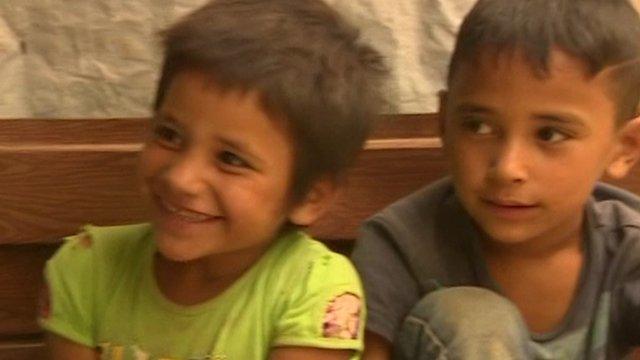

Syrian boys make the most of life at a refugee camp in Lebanon

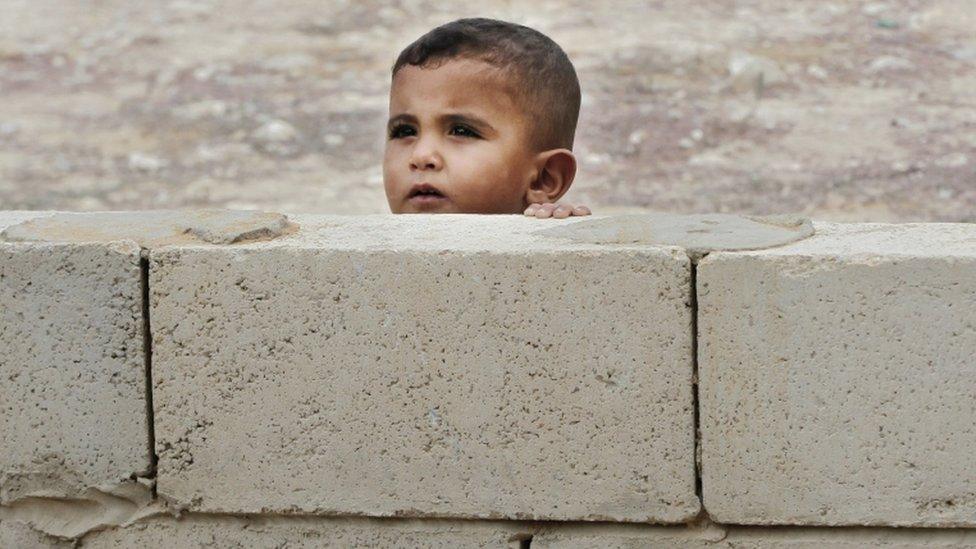

The little children trailing round behind us rush forward in their excitement, herding me into their makeshift schoolroom.

One Syrian boy happily shows a model he has made out of cardboard - a neat house, complete with a shiny red roof, bright blue walls and tiny windows that swing open.

It is a bitter sweet achievement.

He has designed his dream house from memory of a time before, for there are no windows to open here.

We are in Lebanon's Bekaa Valley, and the schoolroom in this camp, like all the 40 or so other buildings, is made of wooden frames on concrete floors, covered in plastic sheeting.

Much of it is decorated with incongruous advertising pictures, black-and-white shots of men in sunglasses and designer stubble.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron wants to take refugees directly from camps, external like this in the Middle East, rather than absorb the people who have already made the journey to Hungary, Greece or Italy.

The logic is that it will stop people making the perilous voyage across the Mediterranean.

It makes a lot of sense. But it may already be too little, and far too late. Taking 4,000 more people each year until 2020 will hardly dent the problem.

The border with Syria is only a few miles across the hill rising above the camp.

The people here can still hear the war they fled, as President Bashar al-Assad's bombs land on a besieged town.

Life getting worse

Life is definitely safer this side of the border. But it is not comfortable.

There are rats, the drinking water is dirty, and while it is now stifling under the September Sun, in winter the snow is 3ft (1m) high and they freeze.

Mzead al-Ali is considering leaving the Bekaa Valley camp

More importantly, life is getting worse and the pressure to leave Lebanon is growing all the time.

One man, Mzead al-Ali, tells me he is on the brink of following those who have made the perilous exodus, leaving his wife and four children, including two seven-month-old twins, behind in the camp, so he can send them money.

His brother left three days ago for Turkey. They haven't heard from him since he went, and don't know if he is safe.

His mother wants to talk about it but has to keep pressing her hands flat against her face, to stop the tears.

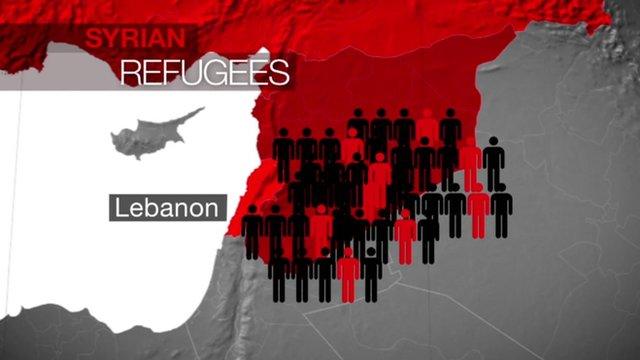

This is not, according to the government here, a refugee camp but a temporary settlement, and there are thousands like it, external.

Lebanon is a country of four million people, and it now hosts well over a million refugees from its war-riven bigger neighbour.

A third live in camps like this, but life is difficult also for others who have more conventional accommodation.

The burden on Lebanon is nearly unbearable, as a government minister told me, and there are rising tensions.

System under strain

The refugees' presence puts pressure on the already dubious efficiency of water and electricity, schooling and health care.

The charities are running out of money, and food aid has been slashed and slashed again. It is due to be cut again soon.

Facilities in the Lebanon camps are under strain

Refugees can't get work permits so can't earn money for the papers they need to renew every year - the $200 (£130) is out of sight for most of them.

Almost unbelievably, they have to pay rent for their camps, and they are not allowed to expand them, even though the population is steadily growing.

The borders are closed, so they can't go back and relatives can't join them.

The schoolroom is funded with aid from Britain.

It is part of the UK government's case that while it make take fewer refugees than other countries, it spends far more in helping people in the Middle East.

But it is noticeable that the schoolroom is decorated with crayon drawings in black, yellow and red - the German flag.

"Next time you come, we have a British flag," says Mr al-Ali, slightly embarrassed.

He says he wants German Chancellor Angela Merkel to send a big ship to take them all to Europe.

There is anger here that the rich Gulf States and Saudi Arabia have done next to nothing to help settle refugees and seem oblivious to the fact that some might think it their responsibility before Europe's.

For this crisis raises some interesting questions about leadership.

Germany's latest intervention, external is fascinating, reflecting a change in attitude that means it is more confident of making foreign policy gestures intended to show leadership in Europe, and which demonstrate a wish to change the world through instruments other than war.

There is also a new impatience with other EU members, and a willingness to lead through example rather than wait for agreement.

Germany, where for a long time foreign workers have been made to feel unloved, wants to show itself as open to the world, a successful and dynamic economy that can absorb, indeed needs, a new workforce.

But it may have unintended consequences.

Families face an uncertain future

Earlier this week, Lebanon's morning newspaper, the Daily Star,, external carried an advert by the Danish government, external, warning it had toughened up its asylum rules and cut benefits to migrants.

The Danes will not be the only ones who worry about the downside of German generosity.

People I met in Lebanon say those who would like to leave Iraq and Afghanistan have heard a message - now is the time to go to Europe, before there is another change of mood and the drawbridge goes up again.

So it is little wonder people in non-governmental organisations (NGOs) feel Mr Cameron may be onto something - it makes sense processing people here, rather than luring them into a dangerous journey.

But while the British policy was announced last week and fleshed out in the Commons, external on Monday, no-one in Lebanon has heard anything officially.

The generous feel it will take a while, the cynical that it is all about the headlines.

Wednesday's announcement on migrant quotas was focused solely on dealing with the crisis within Europe, but there has not even been a whisper of a coordinated European approach using camps in the Middle East, which is what would seem to make the most sense.

It is the death of one toddler on a Turkish shore and the sight of thousands of people dragging themselves across Europe that has focused the minds of politicians on this crisis on our continent.

There is a clear need, somehow, to absorb - or, some might argue, return - these people.

Future problems

But the far greater crisis is elsewhere, and indeed is also in the future.

Mass migration is not just the by-product of one horrible war, or even several conflicts and vile regimes but, in part, the result of the growing aspirations, understanding and opportunity that globalisation brings.

Biafra, external did not send thousands of the dispossessed into Europe.

Biafran civil war:

The Biafran civil war shocked the world

On 30 May 1967, the head of the Eastern Region of Nigeria, Col Emeka Ojukwu, unilaterally declared the independent Republic of Biafra.

The Biafran forces were pushed back after initial military gains.

More than two years later, after one million civilians had died in fighting and from famine, Biafra was reabsorbed into Nigeria.

Thirty years ago, the Ethiopian famine produced Live Aid, external - it meant thousands of people packing into a concert venue in central London for a day, not thousands of the displaced crowding on to trains and lorries for years.

When the cities and farmlands of millions people disappear under the waves, external, it will not be so.

When nations fight wars over precious water, external, populations will march, not in protest, but to happier lands.

It is genuinely hard for politicians in democracies to think beyond four-year cycles, and the next day's headlines.

But perhaps it is time they made a start.

You can listen to our programme from Beirut here.

- Published7 September 2015

- Published7 September 2015

- Published7 September 2015

- Published5 January 2015