Cyber-suspicion strains US-China relations

- Published

China and the US want to strike a deal on the best way to control the internet

Cybersecurity - an issue once obscure - is now at the centre of US-China relations.

In Cold War days, nuclear arms control might have topped the agenda of a major summit - but now when leaders meet, they are looking at how to avoid an escalating cyber-arms race.

Tension has grown in recent years and is the sign of a wider struggle over establishing the rules of the road for the internet as the US and other countries battle to define what constitutes acceptable behaviour and how to deter actions that cross those lines.

American officials have been making their views about Chinese state-sponsored cyber-espionage clear in the run up to this week's meetings.

"This isn't a mild irritation, it's an economic and national security concern to the United States," US national security adviser Susan Rice said, external.

"It puts enormous strain on our bilateral relationship, and it is a critical factor in determining the future trajectory of US-China ties."

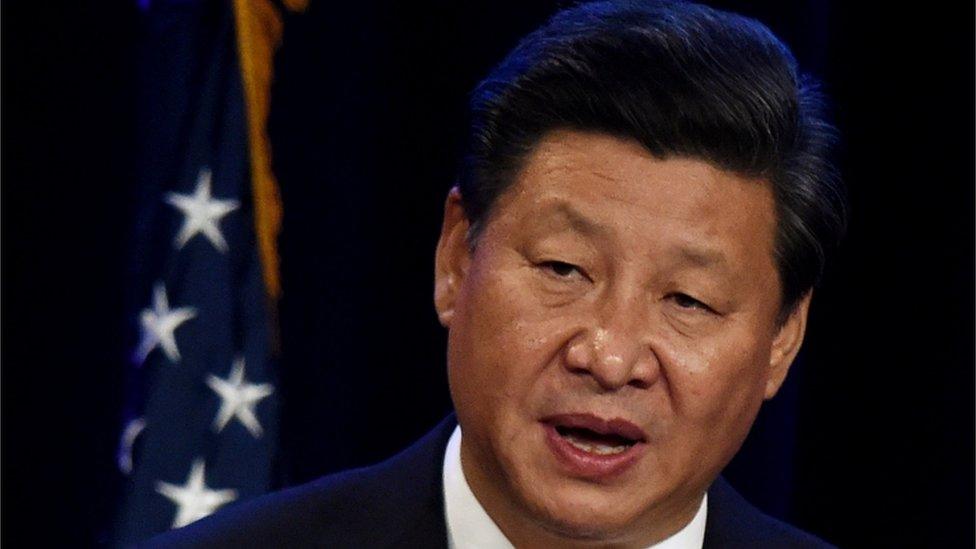

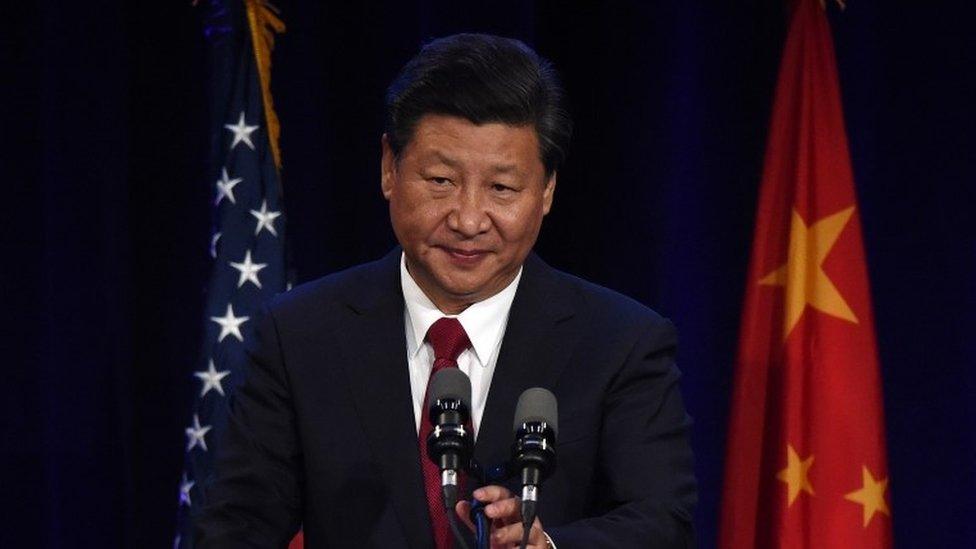

President Xi Jinping, meanwhile, denied such activity was taking place and the Chinese media have stressed how "regrettable" it is that the US has taken on antagonistic position, arguing that Washington's criticism reflects an arrogance and "hegemonic mentality", especially when the US spies on the world.

Both sides argue that developing consensus between the country that founded the internet and the one that now contains the most users is vital - but what that consensus looks like is highly contested.

Arms control

Reports suggest the US and China are negotiating some form of "arms control" for cyberspace - for instance agreeing not to be first to target the other's critical infrastructure in peacetime.

But that is a relatively easy step - more important is the attempt to establish norms of behaviour.

President Xi denies the existence of Chinese state-sponsored cyber-espionage

China is keener on norms that facilitate certain forms of state control over the internet, to deal with its concerns about US dominance and the subversive nature of unregulated flows of information.

The US would like to say it is not just certain kinds of destructive attacks that are unacceptable but also economic espionage, as it defines it.

The message from Washington is that governments spying on governments in cyberspace is fine but they should not spy on companies for commercial gain.

Susan Rice said US-China ties were under strain

However, that is a definition that China and others may see as suiting America's interests and not theirs.

America's annoyance is based on the activities of certain units of China's People's Liberation Army alleged to be stealing intellectual property and business-sensitive information from US companies.

Snowden factor

Just over two years ago, President Obama was preparing to confront the Chinese leader at a previous summit in California over this issue: cyber-spying was top of the agenda.

"We were spring-loaded," says one former US intelligence official.

But then something went wrong.

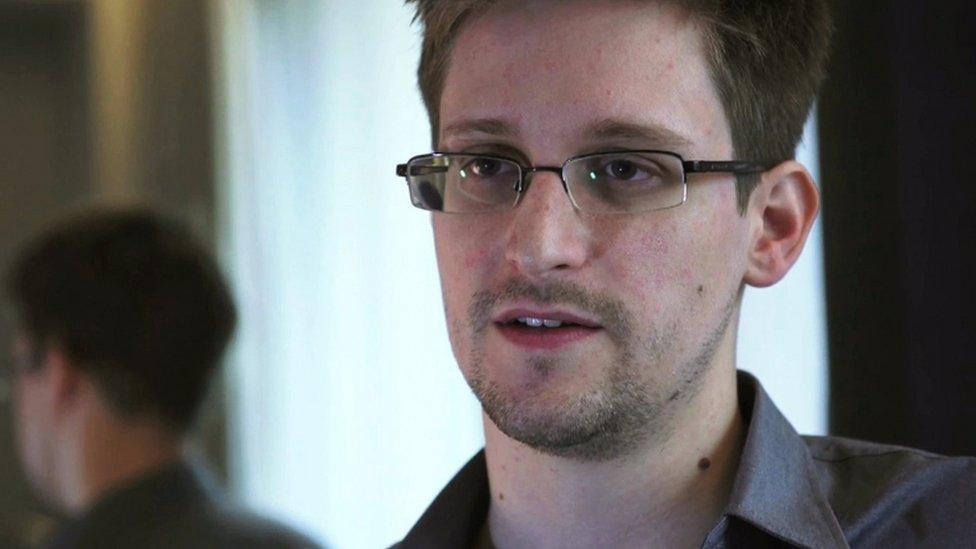

The Snowden revelations put the US on the back foot

Two days before the summit opened, the first stories emerged based on documents taken from the US National Security Agency by Edward Snowden, external.

This completely threw Washington's plans and switched the focus onto US - and not Chinese - espionage in cyberspace.

It took Washington a year after the Snowden disclosures to summon the energy for another push.

In May 2014, US Department of Justice issued charges against five Chinese hacker, externals for carrying out cyber-espionage against US companies.

These hackers all worked for the Chinese military, and some were even pictured in their military uniform.

So far though, the signs are that US attempts at deterrence - first by pointing the finger and then by issuing indictments - have not altered Chinese behaviour.

That has led to questions about what to do next.

US accused

Chinese officials argue that when it comes to cyber-spying, they are more sinned against than sinning and that it is the US that is the greatest problem because of the way it uses its dominant position to control the internet and facilitate its preferred forms of espionage.

They also chafe at definitions that allow US spying on foreign companies and governments for national economic gain (for instance trade positions) but say other forms of commercial espionage are wrong.

The Chinese elite sees economic growth as a national security issue, given that underpins the survival of the current political order.

The cyber-tensions over espionage have also spilled out into issues for US tech companies trying to operate in China.

They are facing pressure both to prove there are no backdoors secretly placed in their products to aid the NSA, while also, in other cases, being asked to ensure there are backdoors to help the Chinese government get round strong encryption.

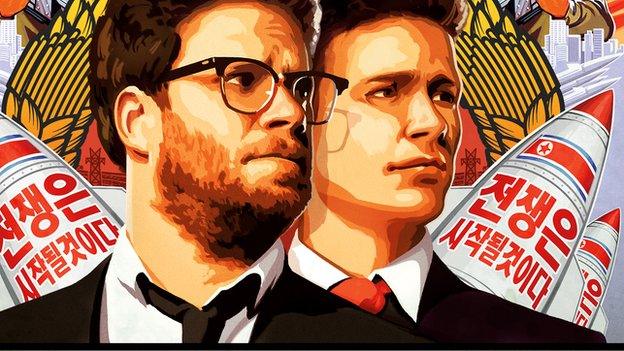

The film The Interview was at the centre of the Sony hack

This year, cyber-tensions ratcheted up another level as US officials were left reeling by the breach of 22 million records, external from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM).

These details were of potentially enormous value for another country's intelligence service either looking for vulnerabilities of employees that could be exploited or trying to identify undercover intelligence operatives (by a process of elimination because their details would not be on this database even though they might pose as regular federal employees).

Top US intelligence officials express sneaking admiration for a great intelligence operation and say that given the chance they would have done the same thing.

This is because by the US's own "norms" of behaviour, this kind of activity is classical espionage and therefore permitted.

As they debate further action against China (including perhaps sanctions against companies), US officials are careful to stress that these would only be in response to commercial espionage and not the kind of state-on-state spying involved in the OPM breach.

China is the main suspect in the OPM breach, although officials say the attribution is not as strong as that that tied North Korea to the attack on Sony Film Studios at the end of 2014.

Attribution difficulties

Attributing the origin of an attack remains one of the key differences between cyberspace and other forms of military activity, including nuclear weapons.

Attribution is sometimes possible but can often take time and is rarely totally conclusive (countries also increasingly use proxies in cyberspace as well to carry out attacks).

Why do US companies continue to do business with China?

The financial benefits of doing business in China usually far outweigh the cost of a research and development team being spied on, or legal papers being read.

China is a massive market for many US companies. For instance, more smartphones are sold there than anywhere else and more than 50% of all the jets Boeing makes are operating in China.

Kicking up a stink about hack attacks and data going astray could jeopardise this cash flow.

The Sony attack raised major questions for US policymakers.

A film studio would not normally be considered part of the critical infrastructure, and yet an attack on it became an issue at the highest level and even led to the US military cyber-command offering a number of retaliatory options to the president (which, officials say, were not chosen, with more traditional responses preferred).

That attack illustrated the problems of attributing attacks and responding to them in cyberspace as well as working out what parts of the private sector the state itself should be tasked with defending.

How do you respond to different forms of cyber-attack - which range from commercial espionage through traditional espionage and into the realms of sabotage?

And which can be directed at companies rather than the state and by actors that are not always easy to identify conclusively?

These are the kind of questions that national security thinkers in all countries are currently struggling with.

And no-one should hold their breath for them being resolved at this summit.

- Published23 September 2015

- Published22 September 2015

- Published21 September 2015

- Published23 September 2015

- Published5 July 2015