A perfect storm of populism

- Published

The coming year is one fraught with challenge for diplomats. Indeed, when it comes to forging international agreements while a perfect storm of populism, identity politics and insecurity roils electorates worldwide, I cannot think of a worse time for diplomacy in 25 years of covering it.

Beset by insecurity (economic and physical), voters in many democracies have moved towards parties rejecting traditional policies or models of co-operation.

The Irish prime minister, addressing a conference of Europe's centre-right parties, warned against "the dangers of populism", referring to the rise of left-wing parties in Spain and Portugal. Meanwhile, similar phrases about the populist spectre have been used in relation to the march of the right in Poland and France.

"Populism" in this context is simply democracy revealing growing electoral extremism or polarisation, and it extends far wider than Europe.

Pat Buchanan, an "outsider" candidate in three US presidential elections, notes: "Nationalism and tribalism and faith - these are the driving forces now, and they are tearing apart transnational institutions all over the world."

In Europe, mass migration has brought matters to a head. Unilateral actions, such as the decision this summer by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban to erect a border fence, have raised the pressure on other European countries and challenged the European Union.

Polls show that Donald Trump is currently leading the race to become the Republican US presidential candidate in 2016

As the migration issue dominates European gatherings, forcing other items off the agenda, some see an existential threat. "No-one can say whether the EU will still exist in this form in 10 years," says the president of the European Parliament - and socialist - Martin Schulz. "The retreat of many governments into nation-based thinking is fatal." The possibility that the UK might vote to leave the EU in 2016 underlines the threat seen by many Eurocrats.

'New era of apartheid'?

Ultimately, though, are leaders who represent popular anxiety about immigration not simply behaving in a democratic fashion? And when Angela Merkel declared Germany's doors open to Syrian refugees, without a parliamentary vote within her own country or consultation with EU partners, that may have been the opposite of populism, but did it not undermine both European co-operation and democracy?

Reflecting on these dilemmas, Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek wrote, external: "We definitely live in interesting times." He suggests the world may be approaching "a new era of apartheid", in which wealthier countries try to seal themselves off from war-torn, poverty-stricken ones.

Marine Le Pen has seen the French National Front garner new support around the country

As this analysis suggests, the darkening horizons for international co-operation extend well beyond Europe. Donald Trump's policies of walling off Mexico or banning Muslims from entering the country have given him the lead in polls for the Republican party presidential nomination.

Are a Trump or a Marine Le Pen really electable? Regardless of the answer, if the centre is shrinking, sapped by political insurgencies on the left and right, it becomes harder to rally support for unpopular international policies - whether they relate to trade, immigration or military action.

Ambitious strongmen

One has to look no further for the effect of this on any collective action than to see how some European countries have refused to accept supposedly mandatory refugee quotas, while others that ostensibly signed up to them dragged their heels.

Try to force the issue, as the European Commission's plans for a new border force could do, by inserting frontier enforcement units on to Europe's periphery - even against the will of the country concerned - and you risk a different kind of crisis.

With their national leaders beset by doubt and political polarisation, quite a few of Europe's political insurgents, from left and right, express their admiration for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

2016 could see the UK referendum on EU membership

At least, their argument goes, he gets things done - for example in Syria. While many, including Barack Obama, compared Mr Putin's actions in Ukraine to the 1930s, the ideological cleavage of those times no longer exists, and the Russian leader has won the admiration of assertive Western nationalists such as Trump and Le Pen.

Russia's recent troubles with Turkey show though that nations guided by ambitious strongmen are also making world politics less predictable as well as less harmonious. The Kremlin has unleashed economic sanctions on Turkey, after the shooting down of a Russian military aircraft, just as its actions in Syria led some to hope that Mr Putin might be about to patch up his relations with the EU.

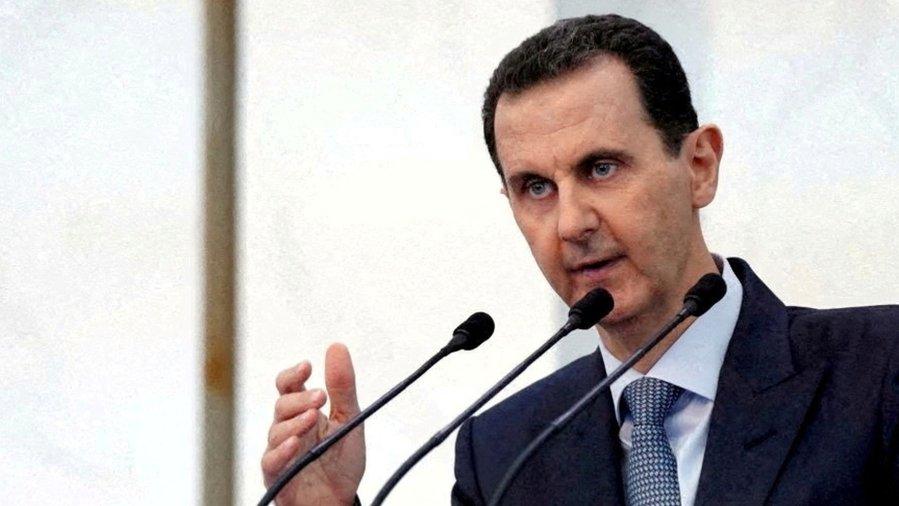

As for the Middle East, a more assertive Saudi monarchy has waded into Yemen, Syria's President Bashar Assad is saying he won't stand down despite the gathering international peace effort, Israel's leaders are in no mood to restart a peace process with the Palestinians, and Iranian hardliners are promising to stand fast in defence of the oppressed Shia across the region.

In 2016 then, there will be big challenges to the international system - from the possibility of the UK leaving the EU, to the strains within the organisation caused by the ongoing migration crisis, sectarian violence in the Middle East, and increasingly ill-tempered trade disputes.

As nationalistic or left-wing rejection of the international system grows, pity the diplomats struggling for consensus.

Mark Urban is diplomatic and defence editor for BBC Newsnight

- Published11 December 2015

- Published7 May 2017

- Published9 December 2024

- Published18 December 2015

- Published17 December 2015