Malala and Muzoon reunite to proclaim benefits of education

- Published

- comments

The girls were reunited in Newcastle, as Lyse Doucet reports

"Are two Malalas better than one?" I ask, only partly in jest, of two smiling teenagers sitting on a purple sofa in a gleaming public library in northern England.

It elicits some quiet giggles.

"Or two Muzoons," 18-year-old Malala Yousafzai immediately chimes in. Muzoon Almellehan, 17, hands clasped demurely in her lap, smiles shyly at the world's most famous campaigner for girls' education who is fast becoming the best of friends.

On a cold rainy day, their two families are reunited in a glass fronted room in Newcastle City Library which offers sweeping views of Muzoon's new home in Britain. Her Syrian family is among the first to come to the UK from refugee camps on Syria's borders.

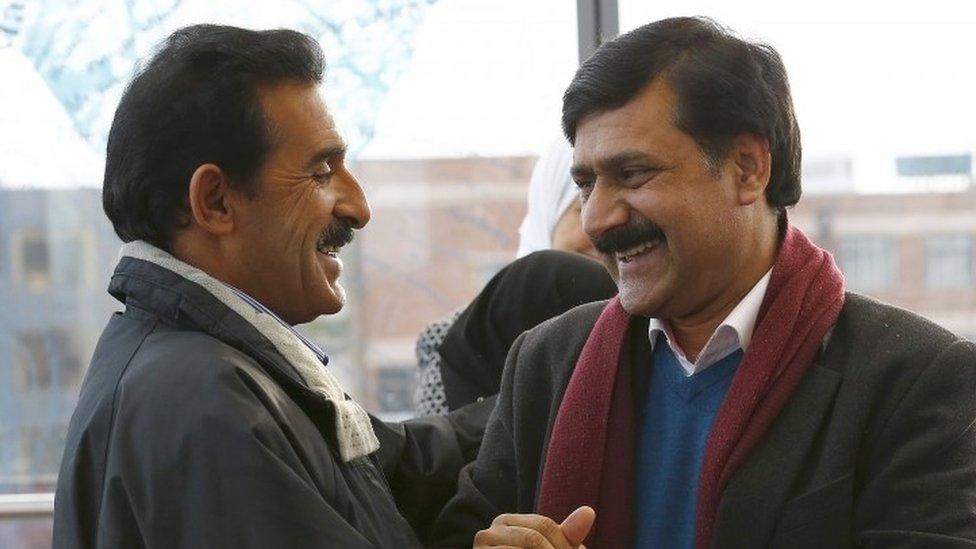

A deep friendship is developing between the two education campaigners

When the Pakistani teenager who survived a Taliban assassination attempt travelled to Syria's border with Jordan nearly two years ago to meet refugees fleeing the war, she heard about a girl they called "the Malala of Syria".

Young Muzoon was going from tent to trailer in the camp, urging nervous parents to educate their daughters instead of marrying them off.

Their teenage lives were changed forever by two very different conflicts. Now they are both schoolgirls in Britain whose lives are changing again.

"We want a Malala-Muzoon army to inspire young girls to stand up for their rights," Malala declares as Muzoon nods firmly in agreement. "We always wanted to work together and now we can."

Their next project for Syrian girls' education will be launched in early February during a major aid conference in London.

As their two daughters chatted, Ziauddin Yousafzai (right) and Rakan Almellehan were deep in discussion with the help of an Arabic translator

The mother of the two campaigners, Eman Almellehan (left) and Torpekai Yousafzai (right) also met in Newcastle

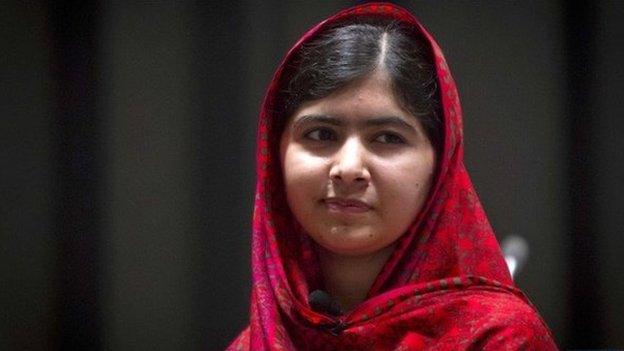

Malala is already an accomplished activist with a fund in her name that's growing in scale and ambition. I saw her mark her entry into adulthood in July with an unusual 18th birthday celebration - she cut her cake, in the shape of a school, as she opened her first school for Syrian girls.

But the young campaigner - already a Nobel laureate - is generous in her praise for her Syrian friend who is a little bit younger and a lot less experienced in the ways of the aid world.

"I was with some schoolgirls in the refugee camp in Jordan and one girl said to me: 'It was wonderful meeting you, but it's not you, it's Muzoon who inspired me to get an education,'" Malala recounts.

Malala Yousafzai has championed education for girls in Pakistan and elsewhere in the world

She also remembers the "horrible situation in camps without electricity where it gets really hot in summer and really cold in winter".

"When you start something, it's always difficult," reflects Muzoon as she ponders her new life in a very different culture.

Her fluency in English has improved considerably in recent years. Mastering it is now one of her goals so she "can talk to Malala about everything" and pursue her dream to become a journalist.

Both girls grew up in conservative Muslim families with fathers who were teachers who instilled in them a love of education.

Malala Yousafzai (seen here visiting the Obamas in the US) is already an accomplished activist with a fund in her name that is growing in scale and ambition

As their two daughters chatted, Ziauddin Yousafzai and Rakan were deep in discussion with the help of an Arabic translator. Their mothers Toor Pekai and Eman also found ways to overcome a language barrier.

The plight of Syria's refugees is clearly on Malala's mind in the midst of the massive movement of people making the perilous journey to reach safety in Europe.

"We say we can't solve this problem because the number of refugees is so huge," she says, citing a figure of four million.

"I actually took out a calculator," she admits with a smile. "I said this is how many refugees there are, and if each country takes about 50,000 or even 25,000 we can solve this."

I point out that countries like Britain, which has promised to take in 20,000 Syrian refugees over the next five years, says they cannot afford to take more.

"I'm not really sure where Britain's economy stands but one thing I am sure of is we can at least help people," she insists. "It's a developed country and we need courage and strength to accept that it's our duty to help people."

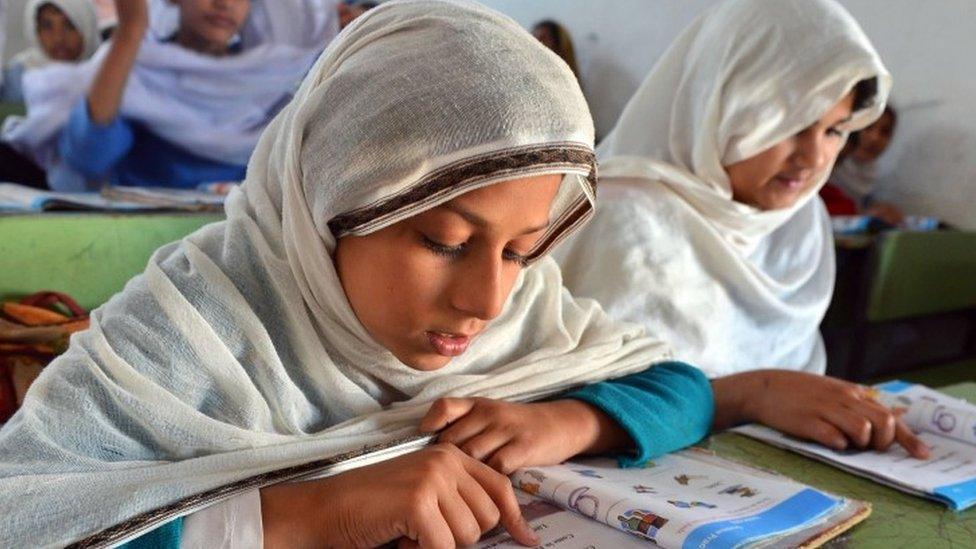

One of Muzoon's biggest concerns is the issue of child brides. Aid agencies say marriages involving teenage refugee girls are increasing at an alarming rate and now make up about a third of marriages in the camps.

"Because of their customs and education, many parents think that by marrying their daughter they will give her a good future," Muzoon explains.

"They're stopping their education because they don't realise the best way to protect their daughters is to educate them."

There is no denying their sense of purpose and, despite their young age, they do make good sense.

"If we are hoping to rebuild Syria one day, that won't happen if two million refugee children are totally deprived of education." Malala explains.

There is another initiative on their minds too.

Muzoon Almellehan argues the best way for mothers to protect their daughters is to educate them

"We are hoping to launch a campaign next year that will mark 2016 as the year we hope war will end and peace will be restored," she says.

"We must be positive and hopeful that my country will be without war," adds Muzoon.

Ending Syria's punishing war next year will test the will of the world's most powerful leaders and most experienced diplomats.

But, in the meantime, two campaigners for girls' education have more than enough of their own work to do, including their own homework.

"What courses are you taking this year?" Malala asks Muzoon when the two schoolgirls retreat to a quiet corner of the library.

It's the beginning of their new conversation. Some of it will be heard around the world.

- Published17 August 2017

- Published21 August 2015

- Published30 November 2015

- Published6 November 2015