Zika virus and microcephaly: Your questions answered

- Published

One of the first doctors who identified the likely link between the Zika virus and thousands of babies being born with underdeveloped brains has been answering your questions.

Usually there are nine cases of microcephaly, the condition linked to the virus, in Brazil's Pernambuco state each year. When Dr Vanessa van der Linden examined five cases in two weeks at the end of August last year, her concerns were raised.

Brazil is at the centre of the Zika outbreak and has reported around 4,000 suspected cases of microcephaly since last October alone.

Here are some of the questions you have been asking Dr van der Linden on the BBC News Facebook page, external.

How did you find out about the surge in cases?

"It was strange to see such a high number of babies with small heads being born all of a sudden," Dr van der Linden says.

Within a few weeks in August and September last year there were 20 cases in two of the state's hospitals, she says.

That is more than twice the number usually reported in a whole year.

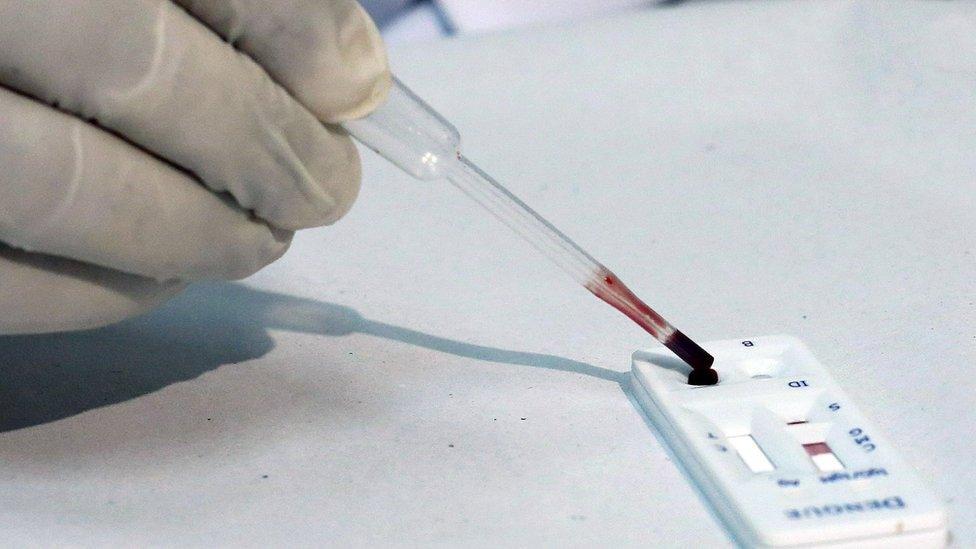

"We tried to explore what happened to the babies. The patterns of our tests pointed to a congenital infection, one that we had not seen before."

What is microcephaly?

Dr van der Linden says that microcephaly is often misunderstood as disease.

"Microcephaly is only a symptom, it is not the disease. The disease is what causes damage to babies' brains and results in small heads," she says.

Microcephaly can have different causes, external, including genetic disorders and infections like syphilis or toxoplasmosis, Dr van der Linden says.

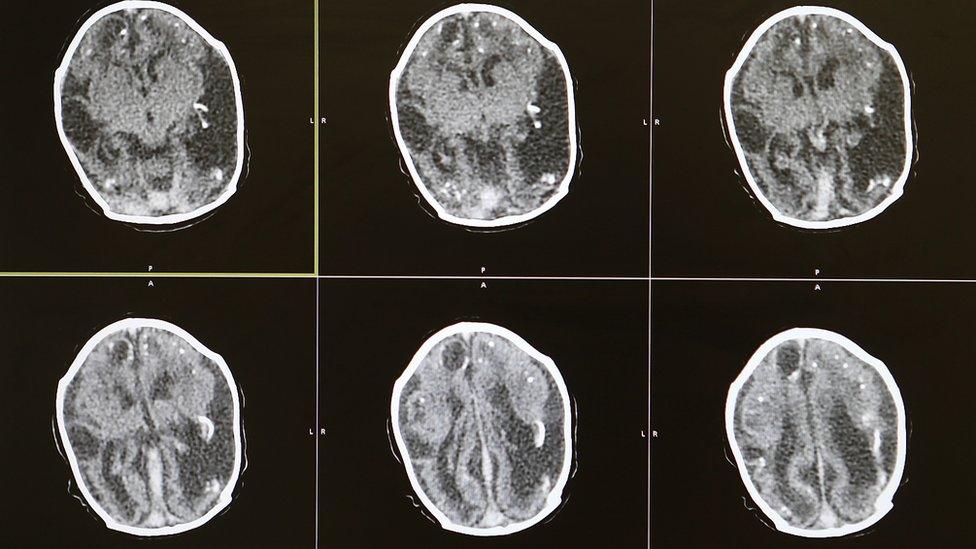

"When we examine a baby with microcephaly, we analyse their brain scans. Some malformations, such as scars in the brain, point us towards congenital infections."

The link between microcephaly and the Zika virus has not been confirmed.

Doctors also found that some babies who died had the virus in their brain and it has been detected in placenta and amniotic fluid too.

Is the Zika virus a danger for a future pregnancy?

According to Dr van der Linden, there are still more questions than answers about the Zika virus.

But she says that future pregnancies are probably not affected by having contracted the virus previously.

At present, doctors estimate that the virus only stays in the body for two weeks.

"After a Zika infection, it is likely that women will develop immunity to the virus. That would mean that there is no risk of contracting Zika during a future pregnancy," Dr van der Linden says.

Several Latin American and Caribbean governments have advised women to delay pregnancies for up to two years.

The WHO has not recommended travel bans with affected countries, but says it is drawing up advice for pregnant women.

What are the symptoms?

Dr Vanessa van der Linden says many of the babies affected seem distressed

The symptoms of microcephaly depend on the severity of the condition, Dr van der Linden explains, external.

"There are some babies with a mild form of microcephaly who develop normally."

The most severe cases cry a lot, are very agitated and barely sleep, she says.

How can microcephaly be treated?

"The virus causes the damage during the pregnancy. The baby is born with the consequences and we cannot reverse those," Dr van der Linden, external says.

There is no cure for microcephaly, she explains, and what can be achieved in terms of treatment depends on the severity of the condition.

"For some babies, rehabilitation can only improve the quality of their lives. Others can learn to walk and communicate via eye contact and smiling."

Babies' heads continue to grow but at a slower rate than normal, she says.

Compiled by Michael Ertl