100 Women 2016: How women are winning online

- Published

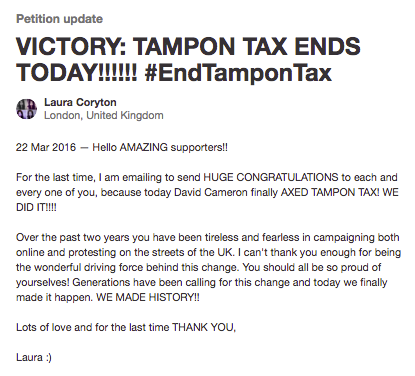

In 2016 the UK government committed to ending Tampon Tax after Laura Coryton's e-petition

Women are more likely to be successful with online campaigns than men, according to one international petition site.

Change.org has found that although men start more petitions, women 'win' their campaigns 14% more often than men do.

Men are 38% more likely to start a petition, despite 57% of the users on Change.org being women. However, women achieve one-and-a-half more signatures on their petitions than men do.

Why do women win more than men?

Change.org is one of many digital petition sites now online, including the UK Parliament site which launched last year. E-petitions on that site that get more than 10,000 signatures receive an official response and after 100,000 signatures are considered for a debate in parliament.

Jen Dulski is in charge of running change.org, which calls itself "the world's platform for change", and its community of 150 million people.

It is on this site that the 2013 campaign to get a woman on British banknotes claimed victory, and a current campaign to erect a Suffragette's statue in London's Parliament Square has drawn the commitment of the city's Mayor, Sadiq Khan.

Jen Dulski believes that there are distinct reasons why women are more successful with their petitions:

"Women are very good at telling their personal stories: the campaigns that are most successful on the site are the ones where people are open - and even vulnerable - about why the issue matters to them, which women do well."

Women, she believes, also share with their networks more effectively. They also sign more petitions, with 70% of signatures coming from women.

The online campaign to get a woman on British banknotes was victorious in 2013 and Jane Austen will soon appear on £10 notes

'I started an online revolution in my onesie'

Laura Coryton was a student in London in 2014 when she began researching an issue that women have campaigned against for generations; the luxury tax on sanitary products.

The existence of this tax in the UK since 1973 convinced Laura that periods were an issue people just did not want to discuss. Sitting on her bed in a onesie, the 23-year old decided to start her own petition entitled "Stop Taxing Periods", external. She shared it with her friends on Facebook and woke up to more than 2000 signatures.

Some 320,000 supporters later, UK Prime Minister David Cameron committed the government to abolishing the "tampon tax" in March 2016.

Laura's believes her campaign was successful because she created a personal connection with supporters

According to Jen Dulski: "Where previously, only influential people and recognised political groups would have been able to work directly with decision makers, online platforms have made it easier for communities to speak with the power of more than one voice, and self-advocate for solutions. This is certainly an important transformation for women."

Laura agrees that the number of women signing petitions marks a new political space: "While 70% of our MPs are male, the same percentage of online petition signers are female.

"It shows that while the parliamentary world does not cater to or accept them as successfully as it does men, women haven't shied away from changing the world. They have conquered the internet and created their own, brand new political space instead."

How to start your own campaign: Laura's guide to winning online

1. Know what you want

Tell people what you want to change, why it needs to change and how it can practically happen. Keep your wording positive and you will motivate people to join you in your campaign.

2. Make it personal

Appeal to people's emotions and make them really want your change to happen. Give your campaign a face and engage with supporters who reach out to you.

3. Create a support network

As your campaign grows, you will face challenges you didn't know existed - it's more fun in a group.

4. Ignore the trolls

Sexist trolls prove that what you are doing is necessary, so use them to empower you to keep campaigning.

5. Protest!

Don't forget the power of engaging offline too. Use social media to create a buzz but then call up newsrooms, knock on doors, organise protests and show you're too big to ignore.

A new political power

In 2011 Ndumie Funda's friend was the victim of "corrective rape" in South Africa - a crime where a lesbian is raped to either punish her or "correct" her sexuality.

Ndumie and her organisation, Luleki Sizwe, were working to support victims when she was told that an online petition could propel her campaign to "all corners of the universe."

Setting herself up in a Cape Town internet cafe, she petitioned the minister of justice to "take action to stop 'corrective rape'", external.

Using social media it took three months for her to get more than 170,000 signatures, and for the South African government to establish a national team to tackle gay and lesbian hate crimes.

Ndumie's was one of the first campaigns to gain international attention and lead to a change in policy.

Her victory also highlighted the potential of the internet to redefine the political power of women.

"We were a small organisation without resources or funding, but we were successful", Ndumie says, "because the driving forces were women, when for too long women have allowed men to lead."

Social Change

The movement against female genital mutilation (FGM) in India is being led by people on social media. Masooma Ranalvi's campaign began when she blogged about her own experience of being cut, before creating a WhatsApp group where women shared their experiences.

According to Masooma, FGM is the "best kept secret in India". Her online petition, external then came from the desire to move from talk to action, and to reach those who can outlaw its sanctioning.

The response has been "phenomenal", she says, surpassing 10,000 signatures in the first week and now sitting at more than 80,000.

Masooma puts her success down to beginning with disclosure of her personal story. "I had to grapple with the shame attached to talking about sexuality," she says. And so she highlighted that "it was not the voice of just one woman, we are a collective of women".

Masooma and Preethi are using social media to break the silence around FGM in India

Preethi Herman, the head of change.org in India, believes there is an inherent male privilege in online campaigning. "If [men] feel strongly about something, they don't think twice about starting a petition," she says.

But she also says that Indian women are more likely to stand against injustice when they can do so online. "The stigma is so much more when you are trying to do it face-to-face, but online you are building support around an issue before you meet the decision maker," she adds.

For Preethi, the most powerful campaigns are run by women like Masooma who "start petition about issues you were not support to talk of".

"The more women understand the potential of using social media and technology, the big shift will be that it is okay to speak up and challenge issues around them."

Our 100 Women season showcases three weeks of inspirational stories about 100 influential and inspirational women around the world . We create documentaries, features and interviews, giving more space for stories that put women at the centre.

We want YOU to get involved with your comments, views and ideas. You can find us on: Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Pinterest, Snapchat, and YouTube using the hashtag #100Women, external. You can also listen to the programmes.

Spread the word by sharing your favourite posts and your own stories using #100women

Other stories you might like:

As it happened: Women take over Wikipedia

- Published17 March 2016

- Published24 July 2013