Fake news in 2016: What it is, what it wasn't, how to help

- Published

In a year in which feelings have appeared to outrank fact, some news has turned out not to be fact but fiction.

"Post-truth" has been nominated as the word of 2016 by Oxford Dictionaries, but how can the media, or you, get better at telling reality from propaganda and mistakes?

There is no such thing as the Denver Guardian

The US election, particularly its winner Donald Trump, and particularly the support for him on social media, has pushed fake news to the forefront, as well as highlighting the potential influence it can bring.

For example, Mr Trump claimed the election would be "rigged". The BBC debunked the claim in late October and similar claims ahead of the 2008 vote, external.

The CCTV supporting the "rigged" theory came from the Christian Times Newspaper, a fake news site not to be confused with the Christian Times (which is a newspaper).

Likewise, there is no such newspaper as the Denver Guardian, despite its website making claims about leaked emails from Hillary Clinton.

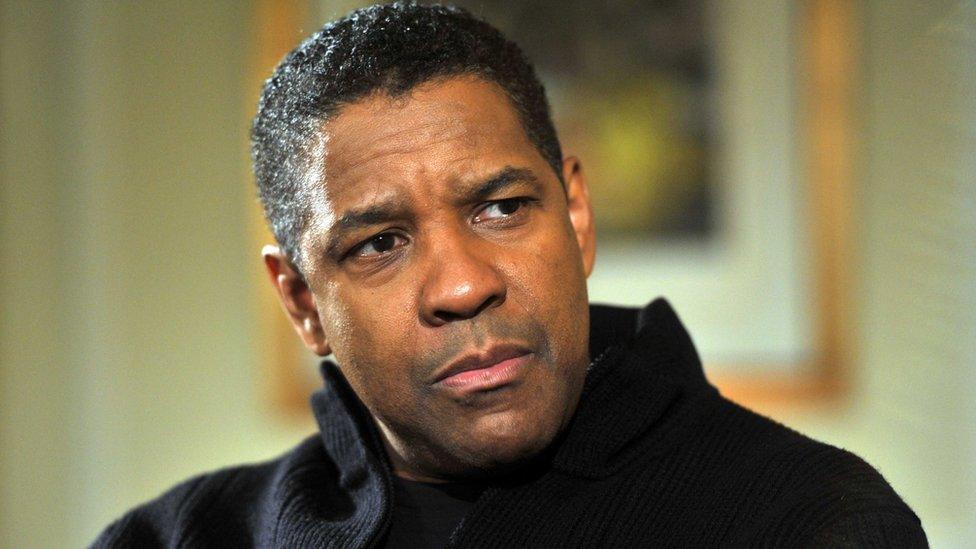

Look at the parallels with the story of Denzel Washington's supposed praise for Donald Trump: a dubious website, an unverified source, and replication and attention through social media. Then larger news organisations report what is happening on social media and add credibility to the story without fact-checking.

Equally, Trump was hit before the election by a claim repeated on social media that he had said in 1998 Republicans were "dumb". It was not true, reported CNN, external, a news organisation which has been heavily criticised by Trump.

After the election came the news Trump was born in Pakistan. No, he really was not. It did not stop some international agencies from repeating the claim.

Perhaps the most notorious example was the conspiracy theory spread about Comet Ping Pong, a pizza restaurant in Washington DC, which led to a man taking an assault rifle to the premises, determined to investigate for himself.

'Fakey McFakeface'

Away from the US elections, fake news breaks down into two wider categories: That which was fabricated and that which was exaggerated or mistaken.

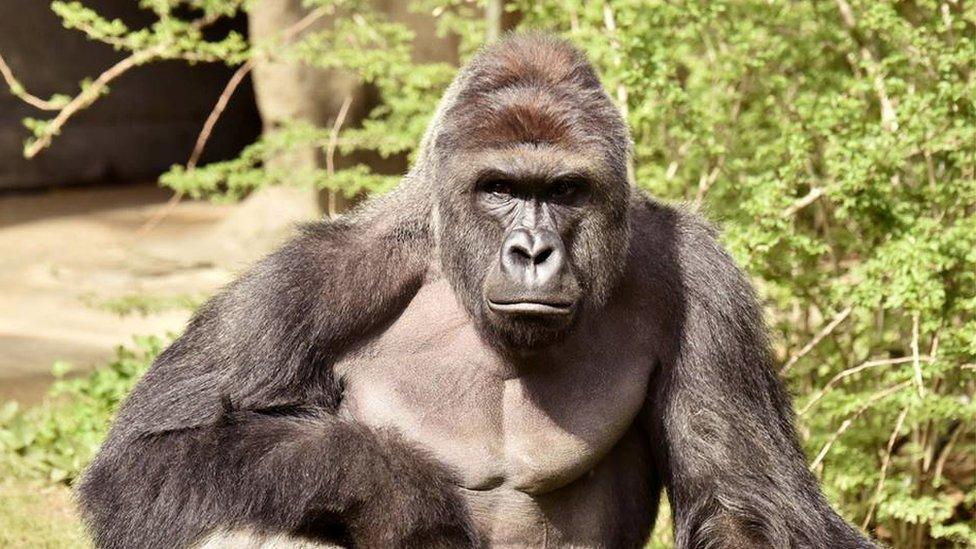

The real Harambe

Was a Chinese zoo about to name a gorilla Harambe McHarambeface? Absolutely not, and the Boston Leader, as with the Denver Guardian or Christian Times Newspaper, appears to be the single source of the news.

The potential appeal of the story was huge. The Leader's article brought together two of the most-talked-about stories: the death of Harambe the gorilla at Cincinnati Zoo and the public vote for the British Antarctic Survey to call a vessel Boaty McBoatface.

Roman Zaripov (right) pictured with Boris Kudryashov - the Russian pensioner who played millionaire Boris Bork.

To prove a point about the ease of making up a story people would want to believe on social media, two young Russians dreamt up a billionaire on Instagram and marketed his non-existent life to the world.

One of them later posted online: "How easy it is to deceive people, and how those who should carefully check information actually don't."

Getting it not quite right

Away from deliberate fiction, exaggeration and mistakes have added to the news-which-was-not in 2016.

Abu Zarin Hussin takes a selfie with one of his snakes

Did a Malaysian fireman marry a snake? No, it was a story which appeared to grow wilder somewhere along the relay chain of information from local media to international news.

At least one newspaper website still has the story up, another has taken it down.

Take a look at this image: is it from the attack on Brussels in March?

This still from a video shows a bomb explosion at Domodedovo airport in Russia in 2011, and is not a picture from Zaventem airport as some claimed on social media

No, it is from an attack at Domodedovo Airport, Moscow.

Some UK and international newspapers tweeted and published several images in the first hours after the attack which could be traced back to the 2011 attack and another from the same year in Minsk, Belarus.

When man-made or natural disasters happen, old footage can resurface. In the rush to add information or gain attention - from wildfires to warzones - video and photographs can be misattributed or mistaken.

The Facebook Lives

But sometimes there is no pressure and images are deliberately misrepresented.

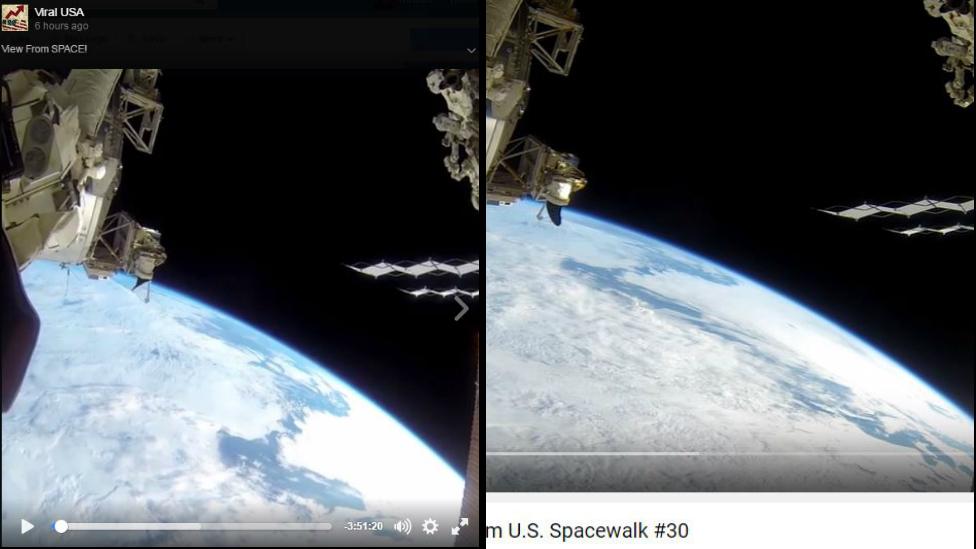

For example, several outlets at several times sought to utilise the uptake of the Facebook Live video-streaming service this year. 'Live' feeds from space on 26 October saw Unilad and Viral USA clock up over 43m viewers for old, looped images from the International Space Station. Initially, people did not question it.

Left: Viral USA video, Right: spacewalk video from 2015

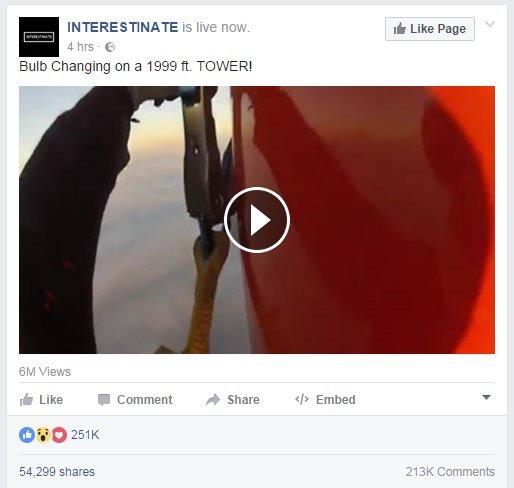

A week later, Interestinate and USA Viral posted four-hour videos which they claimed to be a live ascent of a 1,999ft (609m) tower. Again, it was not questioned, it gained thousands of shares and reactions, and millions of views, each turning up in the timeline of other Facebook users. However, it was not true.

What you can do

So whether you read, repeat or repost news in 2017, here are things to ask yourself:

Have I heard of the publisher before?

Is this the source I think it is, or does it sound a bit like them?

Can I point to where this happened on a map?

Has this been reported anywhere else?

Is there more than one piece of evidence for this claim?

Could this be something else?

We have also produced this guide to reporting fake news on social media and Google News has launched a fact-check service.

Produced by the UGC and Social News team

- Published5 December 2016

- Published27 November 2016