US election: Fake news becomes the news

- Published

Whoever ends up as president one thing is certain: the fakers will keep faking it.

This campaign has been a vector for a whole array of fake news - from the demonstrably false to the misrepresented truth. Here is the best of the worst.

Lies as facts

We have previously written about how to spot a fake US Election report in the case of fraudulent claims about voter fraud in the Democratic primaries. It covers the use of simulacra sites to propagate false news.

These fake sites, which deliberately imitate a genuine news platform, are increasingly common and can go largely unchecked by large social media platforms where they prosper, as investigated by BBC Trending.

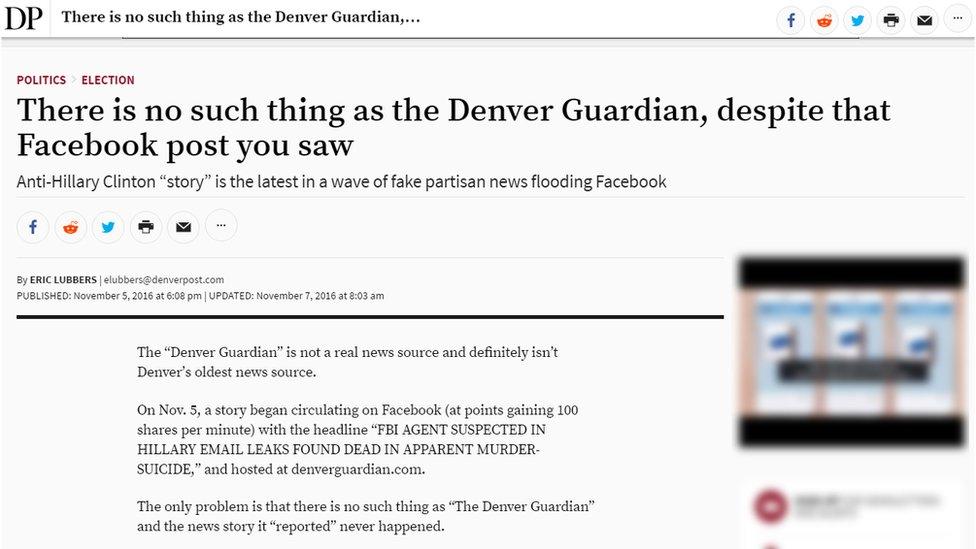

The most recent example to challenge this fakery comes from The Denver Post's "there's no such thing as The Denver Guardian",, external which calls out an entirely false claim about leaked Clinton emails.

Not only is it a false claim, it is a completely fabricated newspaper.

The Denver Post goes on the offensive over fake news on its patch

It also points to one of the key players in the spread of fake news during the campaign: the social media platform Facebook and its news feed algorithm.

Some sites such as Vox have called on Facebook to accept its part in the spread of fake news., external

For its part, the social media giant continues to see itself as a neutral platform while tinkering with its editorial functions.

The price of influence

At its most basic, fake and misleading news is propaganda designed to influence an audience into a particular decision.

That could be which way to cast its vote or part of a more complicated political game.

A report in The Sun, external claims social media bots - automated accounts - on Twitter could sway the election.

It cites research which claims that up to 20% of US Election related tweets could be from automated accounts, external and that "they can negatively affect democratic political discussion rather than improving it".

Post-truth? Just wrong

While this may have been easily disproved, it is more difficult to deal with events recast as something else, even when presented with evidence.

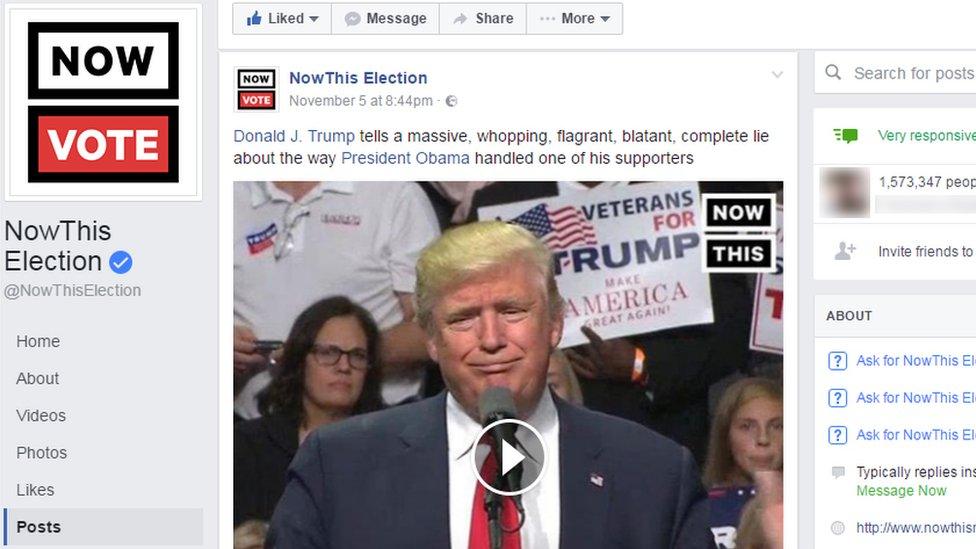

The best example we've seen explaining this phenomena in the campaign is from Now This Election, who juxtaposed Donald Trump's account, external of President Obama dealing with a Trump supporter with video of the actual event.

It has been viewed more than 38 million times and shared in excess of 577,000.

Now This Election calls out Trump for a "whopping, flagrant, blatant, complete lie"

Closer to home, media outlet The Canary misleads with claims that "a major media outlet just revealed who won the US election… a week in advance"., external

It further claims that "in October, the BBC and The Guardian both ran stories questioning the veracity of the election results".

Except the BBC story does not. In fact it assesses the validity of claims that the US election is rigged, finding that there's "no justification for concern about widespread voter fraud".

Two strikes on our fake news checklist: headline fails to deliver in the story and evidence from an original source which contradicts and is misrepresented.

Analysis by Buzzfeed News, external of this new generation of hyper-partisan news sites found that "three big right-wing Facebook pages published false or misleading information 38% of the time during the period analysed and three large left-wing pages did so in nearly 20% of posts."

That is not a margin of error, that is just plain wrong.

Profitable lies

Fake news is no longer just about catching someone out with a prank site. It is lucrative.

Not real, but model planes modelled on Trump and Clinton

The scale and size is now industrial. Meta, external and The Guardian, external have reported on a Macedonian connection, which Buzzfeed has since expanded, external, demonstrating the lucractive potential of tapping into the high volume of traffic generated from the combination of pro-Trump fabrications and Facebook's market dominance.

That article quoted one student who said that his friend could earn $5,000 (£4,035) per month, or sometimes $3,000 (£2,400) per day when he gets a hit on Facebook.

Can truth win out?

When NPR committed to the task of fact checking the presidential debates to change people's opinions, it asked whether fact checks matter, external and concluded that it works sometimes but is difficult to change a stubborn mind.

Brendan Nyhan, a professor of government at Dartmouth University, reviewing the evidence in the election campaign, external found that it is "mostly true" that fact-checking can change people's views.

A bleaker assessment by the New York Times' Farhad Manjoo is that "... the dynamics of how information moves online today, pretty much everything conspires against truth.", external

By Alex Murray, BBC Social News and UGC Team

- Published6 November 2016