John Simpson: My 50 years with the BBC

- Published

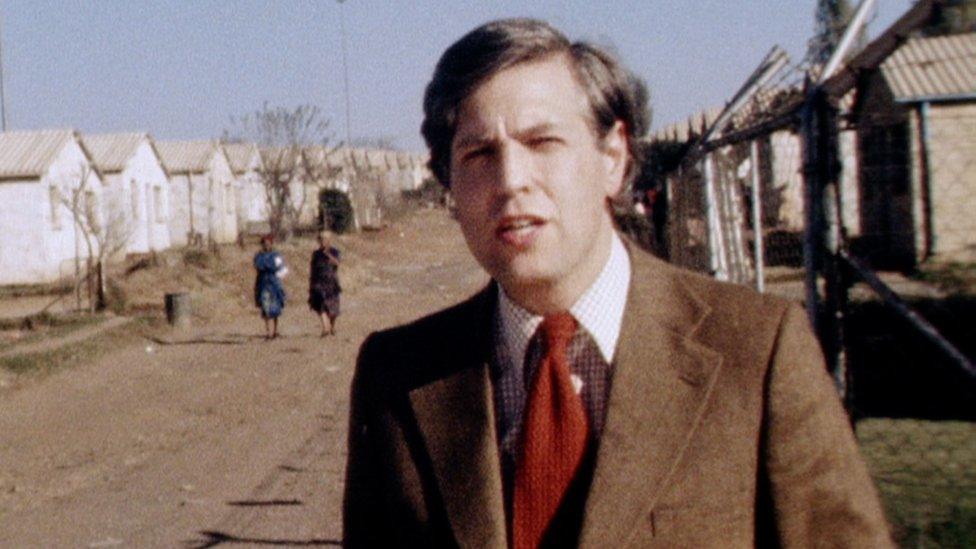

John Simpson reporting from Soweto in the South Africa of the 1970s

The world has changed hugely since the day in 1966 when I first started work at the BBC.

In those days, America seemed infinitely far ahead of the rest of the world. Russia was entering its long, sclerotic phase when no change, political or economic, was allowed. Mao Zedong was just about to impose the horrors of the Cultural Revolution on China. Europe was still getting over the ravages of World War Two.

As for Britain, it was a stodgy place, stuck in its old class system. It scarcely had a tourism industry: the idea that anyone might want to visit Britain for a holiday made people smile.

Within a couple of years or so, much of this had changed.

The United States was convulsed by the Vietnam War protests, and never quite got its old dominance back, the Soviet grip on Eastern Europe was challenged, Europe began its long rise to wealth and influence... and Swinging London became the capital of the world.

As a BBC correspondent, I've been lucky enough to be an eyewitness to many of the great events which have changed our lives.

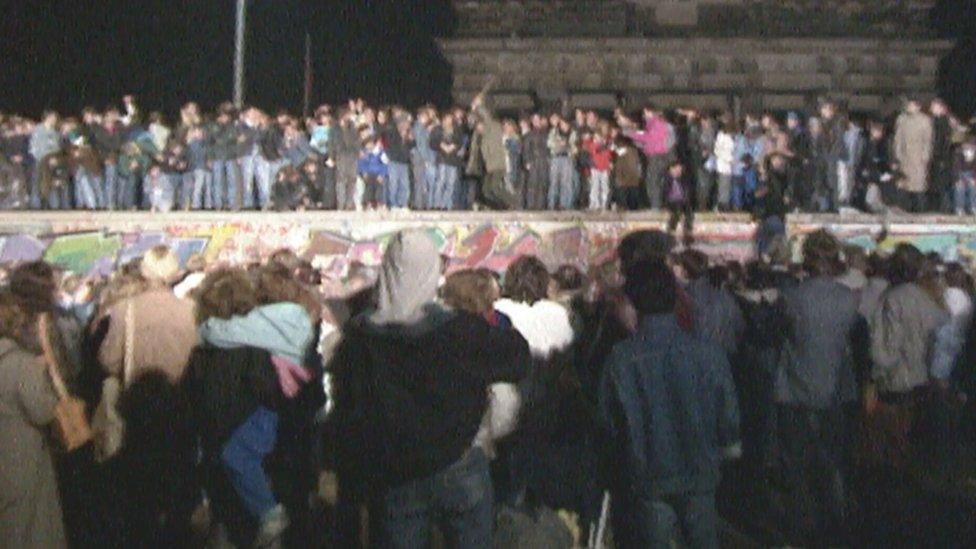

The fall of the Berlin Wall - which presaged the collapse of the Soviet Union

I saw the challenge to apartheid during the Soweto Uprising in the mid-1970s. I watched the revolution in Iran unfold, and give Muslims everywhere a new pride in themselves.

I reported on the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the rise of Mikhail Gorbachev, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent collapse of Marxism-Leninism in Europe, the end of apartheid in South Africa, the savagery of the Bosnian war.

I watched the rise and fall and rise of the Taliban and other extremist Islamic groups, the destruction of Saddam Hussein and the civil war in Iraq which followed, the revolutions against dictators like Colonel Gaddafi, the opening up of China and the ascent of Vladimir Putin and his annexation of Crimea two years ago.

It just shows that if you can hang on to the tail of human history tightly enough, it will take you just about everywhere.

In my professional lifetime, we've seen the world go through two distinct phases. The first was the bipolar world in which Washington and Moscow ordered everything to suit themselves.

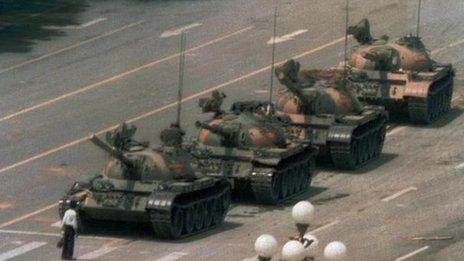

In Tiananmen Square during the Communist Party's crackdown on democracy protesters in 1989

That ended on 9 November 1989, when the East German leadership, without realising the consequences, opened up the Berlin Wall to anyone who wanted to cross into the West. Over the next six weeks the entire Soviet empire in Eastern Europe collapsed, and the Soviet Union itself followed in August 1991.

The second phase has been with us ever since: a weakening US, a damaged Russia, and a rising China. Maybe, after Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, this phase too has now come to an end, and Anglo/Euro/American power is on the way down.

If so, the third phase will bring more of the kind of brutality that is currently being inflicted on Aleppo by the Syrian government and its Russian backers: no-holds-barred violence, no one exempt from the barrel-bombs and the missiles.

Yet much of the world has been a lot better off during the post-1989 phase than when it started.

There's been a dramatic decline in wars fought between states. Civil wars increased in number after 1989, but have declined ever since. In the 1950s, wars caused almost 250 deaths per million people; now the figure is fewer than 10 per million.

High-intensity conflicts have more than halved since the end of the Cold War. Freedom has greatly increased. There are nearly a hundred democracies today, compared with fewer than 40 in 1966.

Dictatorships, getting on for 90 in 1966, are now down to 20. Gross dictators like Saddam Hussein and Col Gaddafi, whom I once specialised in interviewing, have mostly vanished.

Terrorism has surged recently, but it is still below the heights it reached between 1970 and 1990. By a great many measurements, human beings run their affairs better now than they did 50 years ago.

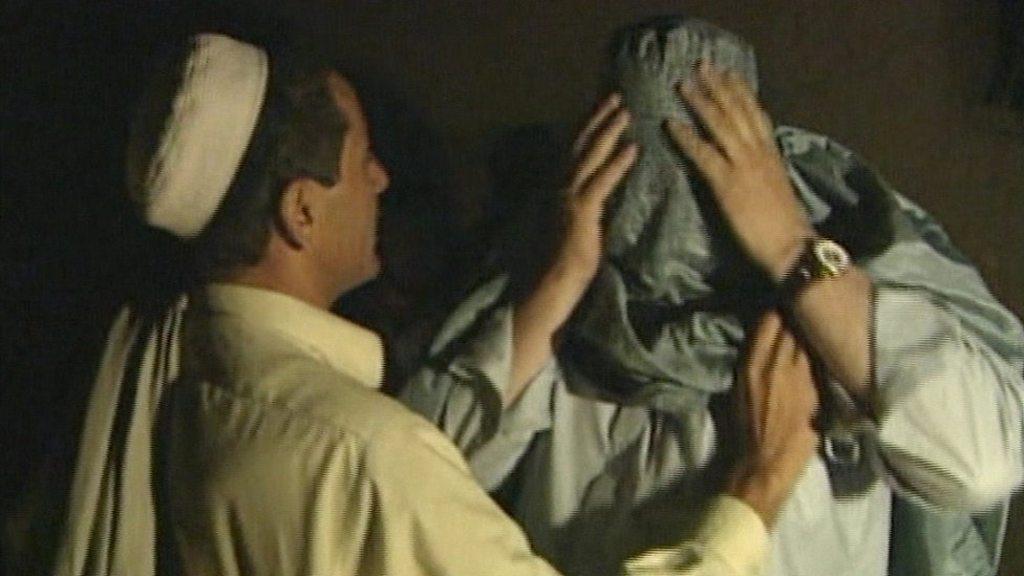

During the Iraq war, Simpson's team was hit by friendly fire, and their translator died

Yet we still don't live happily ever after.

Take South Africa. It was the highest point of my career so far to witness the joyful arrival in power of Nelson Mandela in 1994. I was proud to call Mandela a friend.

Now, crime and the ANC's gross corruption have brought the dream down. When I was in South Africa recently, young black kids told me that Mandela was an Uncle Tom who just did white people's bidding.

In my 50 years I've reported on 48 wars, revolutions and insurrections: a terrible compilation of death and violence.

I've seen at first hand three of the modern world's most notorious massacres: Sabra and Chatila in 1982, the gassing of the Kurds by Saddam Hussein at Halabjeh in 1988, and the shooting down of hundreds of people in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

You don't simply shrug off experiences like these.

Yet in some ways it was the death of a single individual which has had the most serious impact on me.

In the run-up to the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, a young Iraqi Kurd, Kamaran Abdurrazak, asked if he could work with me as a translator.

He was standing beside me on the day when an American Navy pilot dropped a 1,000lb (454kg) bomb right into the middle of the group of US and Kurdish soldiers we were filming. Seventeen people died, mostly burned to death; Kamaran was hit in the legs by a large chunk of shrapnel. He died soon afterwards of shock and blood loss.

Paying respects at the grave of Kamaran Abdurrazak in northern Iraq

I've never got over the guilt at having inadvertently led him to his death.

As a way of marking my 50th anniversary with the BBC, I have made a film for BBC One's Panorama programme. This gave me the chance to go back to see Kamaran's mother in Erbil, in northern Iraq.

I was deeply nervous, but she greeted me with grace and gentleness. "Of course I forgive you," she said, and I wept.

Half a century ago the BBC would have cut out the bit where the tears ran down my face: in 1966, BBC correspondents didn't show emotion on camera. Now it's no longer unacceptable.

In my 50-year career I've looked on while entire nations have escaped from oppression, and great historical wrongs have been righted.

But maybe, as a result of those 50 years, I've been liberated as a person, too.

John Simpson: 50 Years on the Frontline is on Panorama on BBC One at 19:30 GMT on Monday, 19 December and available to view later via BBC iPlayer.

- Published26 October 2014

- Published22 September 2016

- Published21 October 2011

- Published21 November 2014

- Published4 June 2014