The year the world changed

- Published

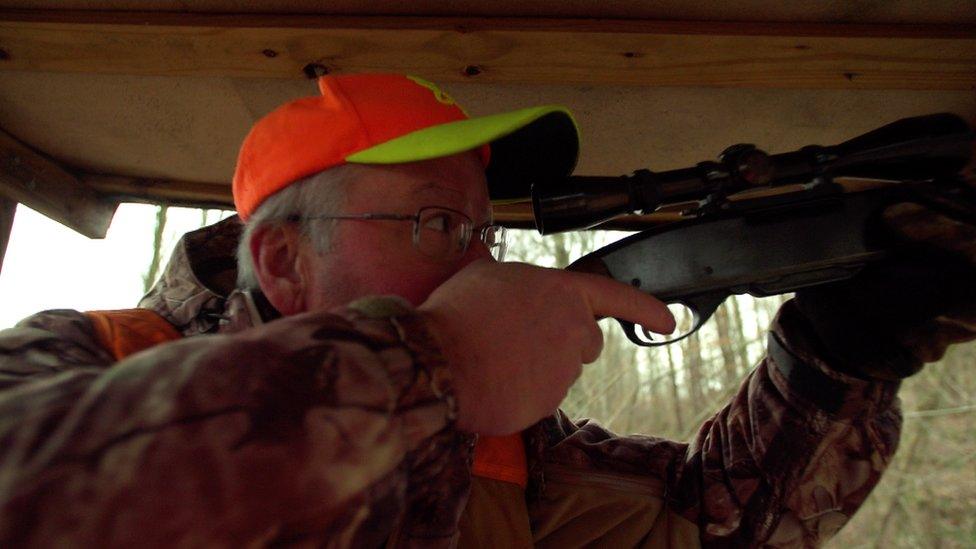

In late November, in the forests of Western Pennsylvania, the deer hunting season begins.

Chuck Erickson has been shooting deer for forty years. "The kids start hunting round here about the age of eight - supervised by an adult of course," he tells me.

Chuck uses his late father's old hunting rifle. Chuck is 56; the gun is older than he is.

He's killed dozens of deer with it over the decades, and the heads of the finest antlered bucks are displayed on the walls of his farmhouse. "We used to hunt for meat," he says, "but now we're mostly trophy hunters." He thinks around 30% of the population in this part of the state get out into the woods to hunt deer at this time of year.

This is Donald Trump country now - blue collar, plain-speaking, patriotic.

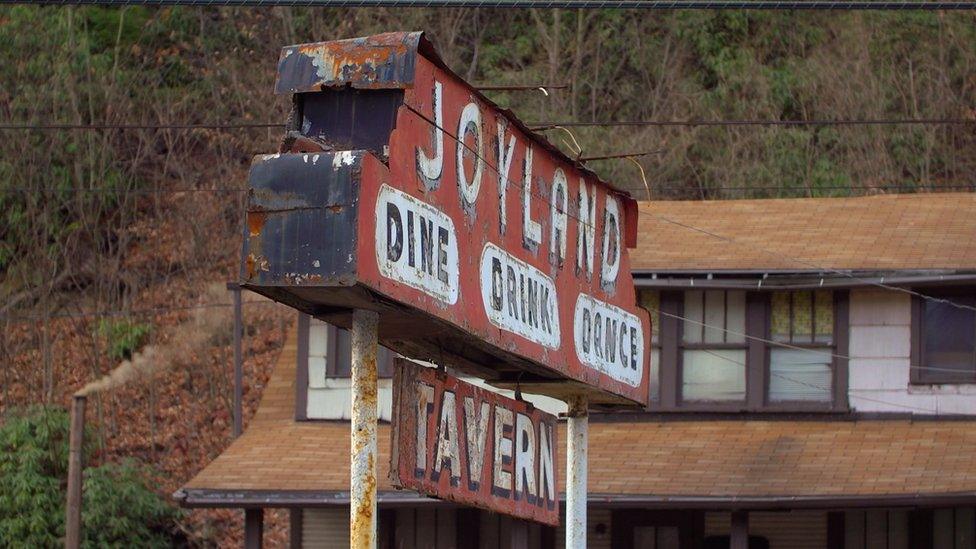

It is a short drive from Chuck's farm to the former steel city of Johnstown.

As you pass through its outskirts you see streets of boarded up houses. The city centre is scarred by the derelict buildings of a once great industry. This is steel and coal territory. But those industries were swept away in the age of global markets and open borders.

Former steeltowns are scarred by decay

Donald Trump promised to reverse that dereliction and bring industry back to America.

"We have the best steel-making coal and there's none getting out of the ground," Chuck told me. "That process to make steel can come back to our shores and that would be tremendous for everybody.

"I think he [Donald Trump] can probably bring that back in the first hundred days of his administration."

He believes that the Trump victory is the start of the re-industrialisation of the United States.

Mr Trump's promise to build barriers to reverse this long industrial decline is a retreat to economic nationalism, to protectionism. It turns the page on a forty-year western economic orthodoxy - the liberal market consensus of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

And Donald Trump's victory finds its British echo in the vote, in June, to leave the European Union.

In the old industrial heartlands of England and Wales, traditional Labour voters defied their party's advice and voted decisively for the Leave side.

The economic revolution that both the US and the UK went through in the 1980s did make both countries richer, in the sense that aggregate wealth grew.

It wasn't supposed to matter that that new wealth would be unevenly shared, that inequality would also grow, because wealth at the top would trickle down; a rising economic tide would lift all boats.

But not all boats were lifted.

Thatcher advisor Ferdinand Mount believes the 'lift all boats' philosophy was too optimistic

There is an irony in this: that the two countries which pursued the deregulating, globalising, free-market reform agenda most vigorously are now the first two countries to have rebelled against open borders.

Ferdinand Mount was a senior adviser to Margaret Thatcher in the early part of her premiership. He ran the Number 10 Policy Unit at the time of the 1983 general election - the second of the three that she won.

"It was a transatlantic borrowing really," he told me. "It was Ronald Reagan who believed that a rising tide would lift all boats. That was, I think, over-optimistic. Overall it was a success, but it failed to create fresh jobs in Wisconsin and Ohio and Michigan, just as it failed to create fresh jobs in, say, Ayrshire and the areas where heavy industry declined."

In both countries 2016 has plunged the left into a huge crisis.

The US Democrats were once absolutely aligned with the interests of blue collar America.

In the mid-20th Century, Franklin Roosevelt hugely expanded the role and power of the federal government, the state in American society, to pursue greater social equality, welfare, health care, job creation, the rebuilding of America's shattered industry.

FDR's New Deal transformed the scope of the American state

How did the Democrats become so detached from their working class base that it took a billionaire property developer to articulate the frustrations of so many who have seen their incomes stagnate or decline over decades?

In the UK, Labour must face the same question.

For in both countries, the mainstream left accepted the post-Thatcher, post-Reagan economic consensus. They came to see the politics of class grievance as a vote loser. They distanced themselves from the 'cloth cap' image in the drive to embrace a more modern, more progressive politics.

In Scotland, once an impregnable fortress in which Labour won every election for fifty years, the party was all but wiped out in last year's UK election; it retained only one MP of the 56 Scotland sends to Westminster.

In the devolved Scottish parliament, Labour is now the third largest party, behind the governing Scottish National Party and the Conservatives.

In England, UKIP activists believe that they are now the authentic voice of working class experience; that June's referendum result is a sign that Labour's traditional support in the old industrial heartlands is now so soft that it is ready to switch sides, just as it did in Scotland.

In Barnsley, in South Yorkshire, I meet Gavin Fenton and Anthea Brownrigg.

For much of their lives, both had voted Labour. Not any more.

"The lack of jobs and lack of opportunities for our young'uns is horrendous," says Gavin. "And with the mass migration under the Labour party under [Tony] Blair in particular, all the wages were compressed. So the poor in this town were getting poorer. So to be let down by the party that I loved as a boy is unforgiveable."

"I think immigration is a big problem as well," adds Anthea. "I think it's just a case of UKIP fills in the gap where Labour once was for the working class."

In Europe, anti-establishment parties of both left and right have been emboldened by Britain's decision to leave the European Union.

How will Germany cope with the challenge of more power in Europe?

Half a dozen EU countries have general elections in 2017. Those contests will be dominated by the question of Europe itself.

In his last visit to Europe before he leaves office, President Obama called on Germany's Angela Merkel.

For 70 years we have thought of leadership of the Western world as being English-speaking, rooted - as it is - in the transatlantic partnership forged during World War Two.

But in 2016 leadership of that old pre-Brexit, pre-Trump conception of what the liberal democratic west should be, has moved to Berlin.

"The Germans are neurotic about leadership in the world," says the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Anne Applebaum.

"They're neurotic about leadership even in Europe. They don't even like to think of themselves as having a foreign policy at all. So no, I don't think they're ready for this moment. But things are beginning to change in Germany with many people now thinking - 'Well, if we don't do it, no-one will.'"

Germany is still profoundly shaped by its history.

The modern Bundesrepublik has built a firewall between itself and previous Germanys. Integrating itself into Europe has been the country's way of normalising itself.

It has been a long, patient process of Europeanising the nation. Germany is now in a period of settled peace with all nine of the neighbours with whom it shares a border.

That has never happened before and was unimaginable even 30 years ago.

Concert pianist Saleem Ashkar believes in his adopted country

Being wedded to the EU has been Germany's act of contrition and of redemption. It has always meant far more to most Germans than mere trade and prosperity.

The international concert pianist Saleem Ashkar is a Palestinian who has settled in Berlin. He speaks warmly and with respect about his adopted country.

"Germany is traumatised by its past," he says. "And it has used that trauma for the good. This is a very thoughtful, very careful country, a country that is very awakened and very careful about the danger of sleepwalking".

So 2016 presents Germany with a new challenge and a new responsibility: how to lead in Europe without appearing to dominate in Europe.

For the idea of German domination still rouses too many ghosts - not least for the Germans themselves.

2016 has changed the shape of the post-Cold War order of things - economically, politically, geo-strategically.

We know what we are in transition from, but not yet what we are in transition to.

You can see Allan Little's film The Year the World Changed on Our World on the BBC World News Channel and on the News Channel in the UK.

- Published1 July 2016

- Published21 November 2016

- Published21 December 2016