Why does everyone keep making Nazi comparisons?

- Published

Associating someone with Nazis - as in this Turkish TV broadcast - is unlikely to win any logical arguments

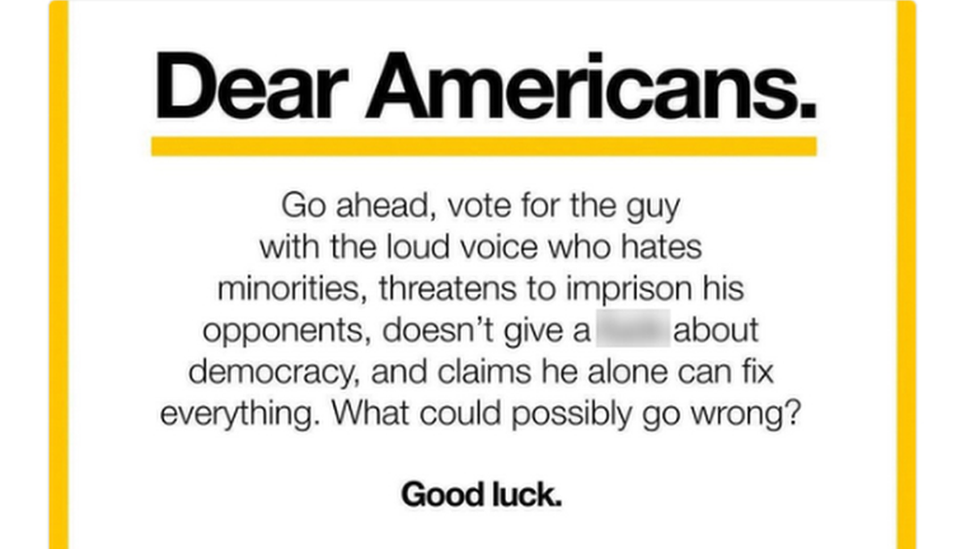

Labelling an opponent as "worse than Hitler" or saying a policy is "like Nazi Germany" is hardly new.

But recently, it has crept into political discussion on an international scale.

As a row between Turkey and the EU deepened in early 2017, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan accused both the Germans and the Dutch of using Nazi tactics.

Similar comparisons plagued the 2016 US presidential election, and they can be found in every medium, from Twitter to national parliaments.

So why is it so widespread?

The answer, according to America's Anti-Defamation League (ADL), is simply that it is the "most available historical event illustrating right versus wrong."

When an argument descends to such fundamentals, the comparison inevitably turns up.

But "misplaced comparisons trivialise this unique tragedy in human history," the ADL's national director Jonathan Greenblatt says, "particularly when public figures invoke the Holocaust in an effort to score political points."

A German float in the Rose Monday parade declaring "blonde is the new brown" referenced the brownshirts - Nazi paramilitaries

Mr Greenblatt made those comments during the US presidential election, at a time when Donald Trump's policy announcements had led to comparisons to Adolf Hitler.

Yet Trump has done the exact same thing himself - comparing the US intelligence agencies, external to "Nazi Germany".

The UK's Boris Johnson compared the EU to the Nazis during the Brexit campaign; a UN investigator used the comparison for Israeli actions in Gaza, external; Russian television has applied the label to the West over the Aleppo crisis.

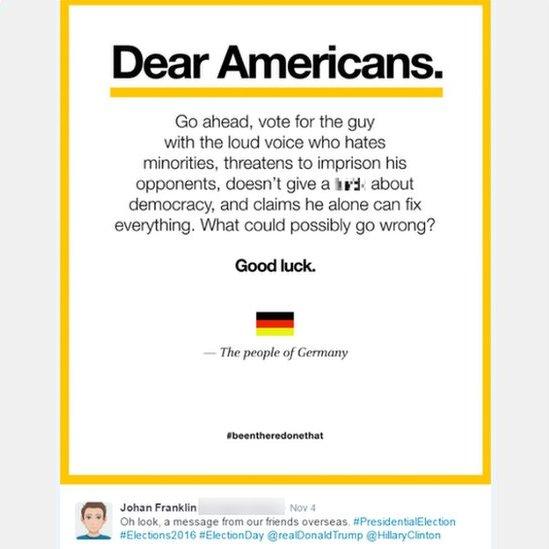

Johan Franklin's election message went viral - though he admits it's a "pretty crude" comparison

In fact, comparing someone to Hitler to invalidate their point is so popular it's been given its own fake Latin name, the reductio ad Hitlerum - a play on the very real logic term reductio ad absurdum. It's mostly used to point out the fallacy of comparing almost anyone to Hitler.

Even the German man who posted a viral image comparing Mr Trump to Hitler during the election acknowledged the comparison was "pretty crude".

Online, everyone becomes Hitler

Of course, nowhere are Nazi slurs more numerous than on the internet - and it's always been that way.

In 1990, an American lawyer named Mike Godwin noticed that arguments on early internet forums would constantly resort to calling the other side a Nazi.

And so Godwin's Law - that if an online discussion goes on long enough sooner or later someone will make a comparison to Hitler - was born, and became a "rule of the internet".

But Godwin originally coined the phrase to point out how ridiculous the comparison always is.

"I wanted to hint that most people who brought Nazis into a debate... weren't being thoughtful and independent. Instead, they were acting just as predictably, and unconsciously, as a log rolling down a hill," he wrote in an opinion column for the Washington Post, external.

In some parts of the internet, the appearance of Godwin's law was seen as a sign the discussion is over.

But the recent spate of high-profile spats proves that it hasn't reduced spurious Hitler references in real life.

A poor argument

When Turkey's President Erdogan levelled accusations of Nazi practices against Germany, it made international headlines.

But for Germans, it's treading old ground in a country which has strong laws against Holocaust denial or glorifying Nazi activity.

"I don't think that most Germans are too fazed about this type of comparison," said Professor Christoph Mick, a historian from the University of Warwick.

"They are used to it, and find it just bizarre that the most democratic and most liberal state in German history is compared to the Third Reich. These comparisons say more about those making [them] than about today's Germany and its politicians."

President Erdogan makes Nazi Germany taunt

So - if a Nazi reference trivialises the Holocaust, is widely acknowledged as a logical fallacy, is ridiculed online, and ignored by the Germans - it must have some persuasive power to have stayed around so long - right?

Not so, according to the English Speaking Union, an educational charity that promotes clear communication and critical thinking.

"Wielding accusations of fascism as an insult doesn't help to get your audience on side - instead, you raise the stakes of the debate, forcing a polarisation between 'good' and 'evil' into a discussion that may have reasonable positions on both sides," says Amanda Moorghen, the group's senior research and resources officer.

"Most of the time, people call others 'Nazis' because they think it will grab the attention of the audience.

"This is a big mistake, because any attention they do get will be drawn to the use of that word, rather than to the nitty gritty of the topic at hand."

And the secret to real success?

"It's far better to save strong words for the argument itself, rather than attacking the people you're arguing with," Amanda Moorghen says.

- Published14 March 2017

- Published5 March 2017

- Published7 November 2016