Why is it so difficult to count dead people?

- Published

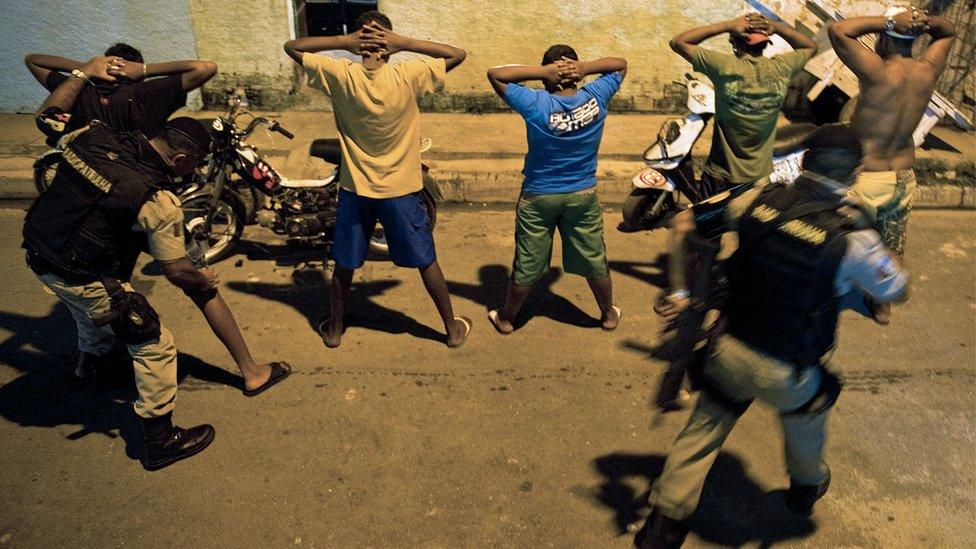

Tens of thousands have died in drug-related violence in Mexico

Think of the horror of people dying violently, and the war in Syria, or a mass shooting may spring to mind. Events like the massacre in Las Vegas highlight the sometimes surprising reality that there are many more people suffering violent deaths in countries "at peace" than there are in war zones.

Every violent death is a tragedy, but getting the numbers right matters.

Reports of deaths in a war zone, a city suffering drug-related violence, or a country plagued by shootings, can drive how the world responds - from media coverage, to business investment, policy decisions and spending by governments and charities.

The trouble is that coming up with accurate figures is extremely hard.

Just one consequence is that although murders very probably kill far more people than wars, it is usually combat deaths that tend to get the most attention.

How many people have died in Syria?

Since the outbreak of war in Syria, the country has been devastated, global powers have been drawn in and huge numbers of people have died.

By February 2016, after almost five years of fighting, the death toll from battle and other causes had reached 470,000, according to the Syrian Center for Policy Research, external.

Two months later the UN special envoy came up with a lower figure of 400,000 , external- far higher than the 250,000 the organisation had estimated eighteen months earlier, after which it stopped counting because it didn't trust the numbers it was getting.

Another estimate came in March 2017, from the London-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, considered one of the most credible sources because of its use of on-the-ground reports.

It suggested that the toll was closer to 320,000 - still horrific, but 150,000 fewer deaths than the upper estimates.

Taken home and buried

Those given the sad task of trying to count war deaths are forced to rely upon a variety of flawed methods.

In Yemen, for example, the United Nations used reports from hospitals to estimate 10,000 war deaths by January 2017.

However, many hospitals have closed and much of the fighting has taken place in rural areas that didn't have any to start with.

Many of the dead are simply taken home by their families and buried.

That could mean that 10,000 is a serious underestimate.

Deaths in Colombia may have been undercounted because news reports are in Spanish

On the other hand, since rural areas are sparsely populated, the UN figure may not be so far off after all.

Elsewhere, some of the most meticulous researchers insist on being able to name a perpetrator before they count a death and use only English language newspapers, to ensure consistency.

This makes details of confirmed deaths robust, and international comparisons simple.

But deaths in messy conflicts where perpetrators are hard to pinpoint, or those which don't get media attention - a problem in rural areas, or under authoritarian regimes that control the media - can be missed.

There can also be a problem where much of the reporting is not in English.

In Colombia, for example, where most coverage is in Spanish, researchers at the Conflict Analysis Resource Center in Bogota estimated that international experts had captured fewer than half the deaths in most years of its guerrilla conflict.

The wrong types of deaths

Meanwhile, in all wars, many people die from disease, hunger, and other "indirect causes".

Should these count as war deaths?

The World Health Organization found that by August 2017, 2,000 Yemenis had died of cholera.

A cholera epidemic in Yemen has affected hundreds of thousands of people

If war hadn't destroyed hospitals and kept doctors from being paid, some of these deaths might have been prevented.

Yet Yemen is a poor country, and even without a war, communicable diseases claim lives.

Researchers at the Small Arms Survey, a think tank in Geneva, suggest that indirect deaths kill three to fifteen times as many people, external as fighting during conflict - depending largely on levels of development, and whether civilian infrastructure is targeted.

In Ukraine, for example, the UN estimates that 10,000 people were killed in battle by the end of 2016 - on a par with Yemen.

But in Ukraine, roads and hospitals still function and a cholera outbreak is unlikely to be very deadly.

Finally, like war deaths, indirect deaths can be manipulated in an attempt to gain an advantage, as researchers suggest happened when Saddam Hussein tricked Unicef inspectors, external into reporting high child mortality in a bid to get sanctions lifted in the early 1990s.

Thus, indirect deaths aren't usually included in war statistics.

Jaw-dropping numbers

By tending to focus on war, the media misses an even more crucial reality: homicides probably kill three to four times more people each year than conflicts.

Between 2007 and 2012, homicides killed an average of 377,000 people a year, external, while about 70,000 died annually in conflict.

Experts at the Geneva Declaration, one of the few think tanks that counts violence across both warfare and crime, estimate that eight out of 10 such deaths, external occur outside conflict zones.

That may seem counterintuitive, but the number of wars worldwide is relatively low and homicides occur in every country.

The numbers can be jaw-dropping.

Homicide rates in large countries like Brazil can exceed deaths in war zones

For instance, in 2015 the Brazilian Forum for Public Security reported more than 58,000 homicides, external - a year in which the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights counted just over 55,000 deaths in the Syrian wa, externalr.

Astounding numbers of homicides are found in many other countries, external, with about 34,000 reported in India, 22,000 in Mexico and 17,000 in Nigeria in 2012, the last year comparable UN data is available.

And the murder of 58 people in a mass shooting in Las Vegas has again highlighted the problem of violence in the United States.

In fact, violent death rates in the US are currently at lows last seen in the 1960s, external, but have been ticking upward over the last three years.

And even at all-time lows, the US remains an anomaly among similar developed democracies, with a murder rate four to five times as high as Western Europe.

Even with Syria and Afghanistan causing war deaths to rise to nearly 100,000 a year today, they remain a fraction of overall homicide numbers.

However, the use of overall numbers rather than a figure which takes into account the size of a country's population can sometimes make a country appear more dangerous than it is.

After Brazil, which has about 10 times Syria's population, India has the second largest number of murders most years.

But with a population of well over a billion people, its homicide rate is remarkably low: just 3.5 per 100,000, or about half the world's average, according to the United Nations Office on Drug Control, external.

And the Igarape Institute, which begins with UNODC's numbers but then cross-checks these with local police, morgues, and think tanks for greater accuracy, puts India's rate at 2.8 per 100,000 - lower than Latvia's.

No corpse, no prosecution

Unsurprisingly, homicide statistics are as bad as war data.

Most countries count homicides in two places - police stations and morgues.

Researchers tend to trust morgue statistics more because police can be under pressure to keep homicide numbers low, whereas morticians tend to be more removed from political influence.

The number of homicides in New Orleans was reported as being twice as high as in Afghanistan

Yet some bodies never make it to morgues, since a murder without a corpse can't be prosecuted.

In Colombia, criminals use chop-houses to destroy bodies, while the Sicilian mafia used to dissolve bodies in vats of acid for similar reasons.

Homicide numbers can sometimes be inflated due to poor record-keeping, but more often, countries have an incentive to downplay numbers.

And only about half of all countries in the world report any homicide statistics at all.

The United Nations does its best to mathematically model data for the rest, but in places like sub-Saharan Africa, where very few countries report, there is little to go on and a likelihood that available numbers underestimate the effects of war and rapidly growing populations.

Rough but illuminating

Given these problems, any statistic on violent deaths should be treated with caution.

But thinking across the boundaries of war and crime can be illuminating, even if numbers are used as rough estimates.

The results can be very surprising.

In 2011, for instance, New Orleans' homicide rate of 57.6 per 100,000, external was on par with the rates of homicides and conflict deaths in Afghanistan that year.

Elsewhere, Mexico has struggled with drug-related violence, the number of homicides steadily increasing, external and - between 2007 and 2014 - reaching 164,000, according to the Mexican government.

That puts it on a par with many wars and exceeds the number of civilian deaths in Iraq and Afghanistan during the same period, according to UN and Iraq Body Count figures, external.

No-one would say that New Orleans or Mexico were at war.

But, as with other places experiencing large numbers of violent deaths, the word "peace" doesn't seem entirely appropriate either.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Rachel Kleinfeld, external is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, external, focusing on issues of rule of law, security, and governance in post-conflict countries, fragile states, and states in transition.

Edited by Duncan Walker