Can war games help us avoid real-world conflict?

- Published

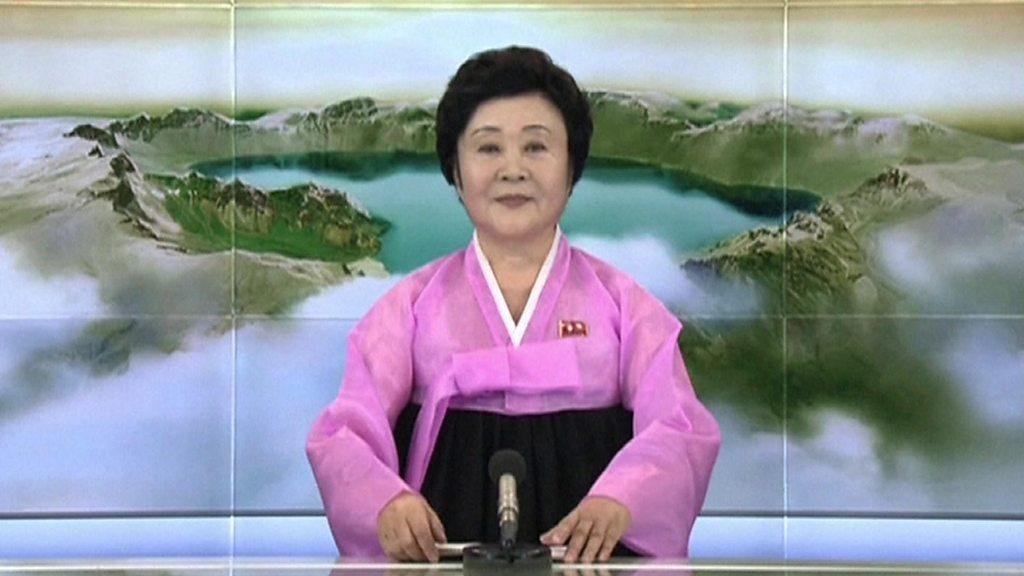

North Korea has just fired off an intercontinental ballistic missile over Japan. Japan is uncertain as to whether the US wants to start a war.

It's trying to find out why a massive American naval fleet has just arrived in the region. But it's not getting any answers. There's chaos in the White House as various factions try to influence the president.

Some of this might sound familiar. But this is not real life. It's the scenario in a war game called Dire Straits, set in 2020.

And it's being acted out, not on the world stage, but in a lecture theatre and seminar rooms at King's College, London.

Rules and referees

More than 100 people are taking part - academics, students, serving military officers and civil servants, as well as a few who do this for a hobby.

To an outsider, the game looks like chaos, but there are rules and referees.

Participants are given a scenario, which develops throughout the exercise

Tables have been set out representing countries.

The participants wear badges with their national flag and their role. There's a Russian president and foreign minister, a UN secretary general, military commanders and even journalists.

It's a noisy mix of debating society and board games: Risk meets Top Trumps meets chess.

On one table, there's a map of the region with cards placed on top with pictures of military hardware such as a US aircraft carrier and a nuclear submarine.

Participants include academics, students, serving military officers and civil servants

Then, there are the "live inserts". Tweets appear on giant television screens to signal another twist in the game. Some of them are the actual tweets of President Trump. It keeps everyone on their toes.

It's all been choreographed by Jim Wallman and Prof Rex Brynen, of McGill University, in Montreal, who has also done these kind of games with the US military.

Prof Brynen says in recent years there's been a "major resurgence of war gaming as a serious analytical and training tool in both the US and UK".

Prof Rex Brynen says there's growing interest in war gaming

In Dire Straits, he's overseeing events in the White House - a room down the corridor from the rest of the world in the lecture theatre. A dozen people are trying to influence President Trump, who's survived another election in this scenario.

Alex Jonas, who plays the role of a beleaguered White House chief of staff, is trying to decide which of the advisers gets access to the president. Alex's real job as a web developer sounds less frantic.

President Trump is not being played by a person.

Instead, there's a board with chance cards that reveal his state of mind. Some are based on his own tweets. Before lunch, one of the cards warns North Korea of "fire and fury", echoing a phrase the president used in August.

Prof Brynen says there are a lot of players trying to influence the president. "He's blowing hot and cold on China, and US ambassadors in the region feel he's not really listening." Some of this might reflect his own views of President Trump.

'Avoid group-think'

Over on the North Korea table, the man playing Kim Jong-un has demanded that his team applaud each decision he makes. The umpire for North Korea is a real-life British military officer, Maj Tom Mouat, who lectures at the Defence Academy, at Shrivenham. His presence suggest this is a serious business.

He says war gaming "allows you to better understand what options you have". "You avoid the group-think mindset," he says.

Each participant takes on a specific role in the unfolding scenario

He gives the example of the US academic Thomas Schelling, who was involved in war gaming during the Cold War and helped identify the need for a "hotline" for the US and Russian presidents to talk.

Philip Sabin, professor of strategic studies at King's College, says war gaming highlights the dangers in a "safe way".

He refers to a recent game involving Russia and its Baltic neighbours, in which nuclear weapons were fired.

"War games are designed to explore how things can go horribly wrong," he says. "That helps you to avoid getting into that situation in real life."

Regional solution?

So what happens at the end of the Dire Straits war game?

An unpredictable US policy led North Korea's neighbours to seek regional solutions. None relied on US leadership in the game.

South Korea secretly prepared the way for its own nuclear weapons programme. Taiwan used the chaos to further its independence from China. The US accelerated the deployment of a new anti-ballistic missile system.

As for North Korea, it made significant advances in its nuclear weapons programme. But no-one was prepared to risk a broader war, and the collapse of a nuclear-armed North Korea was seen as even more dangerous.

In the end, the major powers helped to de-escalate the crisis. Even in war gaming - where the stakes are of course much lower than real life - jaw-jaw is often better than war-war.

- Published5 September 2017

- Published4 September 2017

- Published3 September 2017

- Published5 April 2017

- Published21 March 2017

- Published6 March 2016

- Published16 January 2015