North Korea: Does latest nuclear test mean war?

- Published

North Korean state media announces "hydrogen bomb" test

South Korea says that North Korea could be preparing more missile launches after details of the isolated nation's latest test - equivalent to a 6.3 magnitude earthquake - emerged over the weekend.

US Secretary of Defence James Mattis says any threat will be met with a "massive military response". President Donald Trump has previously promised "fire and fury".

Is there a diplomatic solution? Or is the crisis heading to an inevitable war?

Defence and diplomatic correspondent Jonathan Marcus answers your questions on North Korea and how the situation might be resolved.

Will there be war?

South Korea carries out live-fire drills in response to the nuclear test

One certainly hopes not. It is hard to imagine any conflict breaking out since the risk of escalation to all-out war would be very likely in these highly-charged times. The US is signalling strongly that the North Koreans should do nothing that might risk a conflict.

All-out war would be catastrophic in terms of lives lost. It might potentially involve the use of nuclear weapons - the first time since the closing stages of the Second World War - which could set a terrifying new precedent in international affairs.

At its close, after terrible destruction, North Korea would no longer exist. That is a given, hence the hope that the Pyongyang regime is rational and understands the risks involved.

Its behaviour, though, amounts to very, very high-stakes brinksmanship.

Who would be the key players and what role would they play?

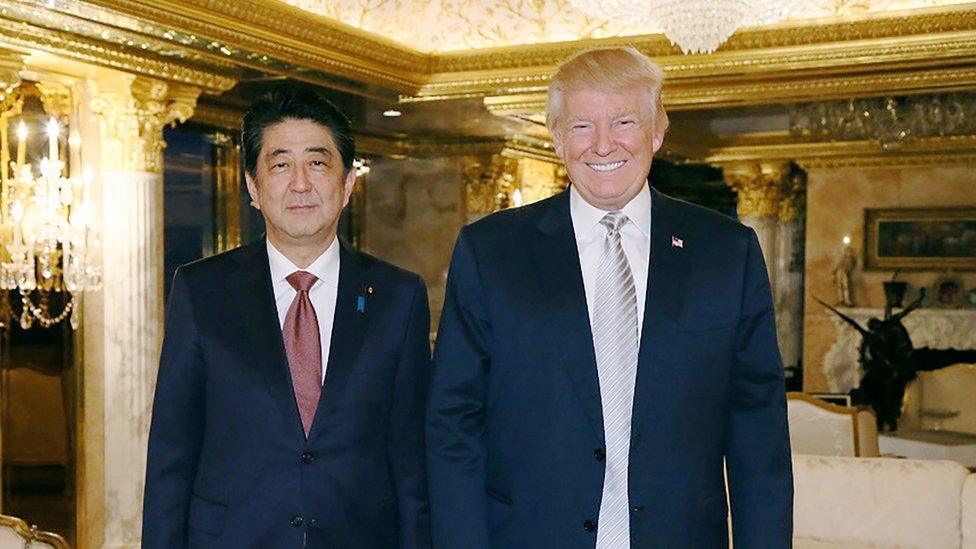

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe meets US President Donald Trump in 2016

Initially it would be North Korea versus the rest - South Korea and the US certainly.

Quite what Japan's precise role would be is hard to say unless it had been attacked directly, but there are large numbers of US troops and bases in Japan.

The US would seek diplomatic support from the UN Security Council and, failing that, also from its allies. How far they might be involved in practical terms is hard to say. We hope this is just an academic question.

Could armed conflict trigger a global nuclear war?

Unlikely. A regional conflict would be bad enough.

Russia, Washington's NATO allies and so on are not directly implicated. However the big question is if there was conflict, what might China do? Would it effectively intervene as it did in the 1950s to ensure the survival of the North Korean regime or would it remain on the sidelines?

It is linked to Pyongyang by a defensive treaty but this does not guarantee Chinese involvement. Again, one hopes that this question is academic.

Why can't the US accept North Korea as a nuclear power?

In August, President Trump said the US would meet North Korean threats with "fire and fury"

For practical purposes, North Korea is already a nuclear power and has had a small nuclear arsenal for some time.

What makes the current crisis more serious is that Pyongyang is now making rapid headway towards a capability to threaten the continental United States with a nuclear-armed missile.

Rolling back North Korea's nuclear and missile programmes may no longer be possible. In the future the emphasis may be upon deterrence and containment.

Practically, the world may have little choice but to reluctantly accept North Korea as a nuclear power. But experts fear the impact this may have on the wider question of nuclear proliferation.

Is there a diplomatic solution?

The exact pace of North Korea's technical progress is hard to determine.

More tests may be necessary and it is hard to know if a North Korean missile and warhead could survive the force upon re-entry into the earth's atmosphere. So they are not there yet but they are moving ever closer.

Until now, the emphasis has been upon rolling back North Korea's nuclear programme. For all the talk about seeking a diplomatic avenue - and that would presumably mean multi-national talks with Pyongyang - it is not clear what the goals of such talks would be.

Is the idea to freeze North Korea's activities? To get it to halt further nuclear and missile tests? And what are the Americans in particular willing to give diplomatically (and probably economically) in return?

There have been talks with Pyongyang in the past. Deals were struck and they were implemented, at least in one case, albeit for a period. It is wrong to assert that there have never been negotiations with Pyongyang, nor that they cannot have a positive outcome. This current North Korean leadership, though, may be another problem.

What about China?

Russia's President Vladimir Putin shakes hands with China's President Xi Jinping in Beijing in 2014

China is key but it is a conflicted party. On the one hand it does not want to see a nuclear-armed North Korea and it has made its view clear to Pyongyang on many occasions.

However, it does not want to see the North Korean regime swept away. This would result in millions of refugees flooding into China and would probably result in a unified Korea very much in the US orbit. This is seen in Beijing as worse than having a difficult nuclear neighbour.

If China were to take the view that the coincidence of a rapidly advancing North Korean nuclear programme and the uncertainties of the Trump Administration's diplomatic capabilities means that there is a very real risk of misunderstanding and catastrophe, then maybe it might bring much greater pressure to bear on Pyongyang.

North Korea is a very isolated country and China is both its major ally and economic prop. There is a lot more that China can do. North Korea's recent testing has been as much an embarrassment to China as it has angered the US. But the Chinese have a difficult diplomatic calculation to make.

China and Russia together have tabled a diplomatic roadmap that proposes the de-nuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula and a peace deal to end the Korean War. In the interim, they say that North Korea should suspend its nuclear and missile testing and that the US and South Korea should suspend large scale military exercises.

North Korea has not shown any interest in this proposal, at least publicly, and the Americans have dismissed it - in the words of US UN Ambassador Nikki Haley - as "insulting".

Produced by Chris Bell, UGC and Social News team

- Published4 September 2017

- Published29 April 2018

- Published3 September 2017