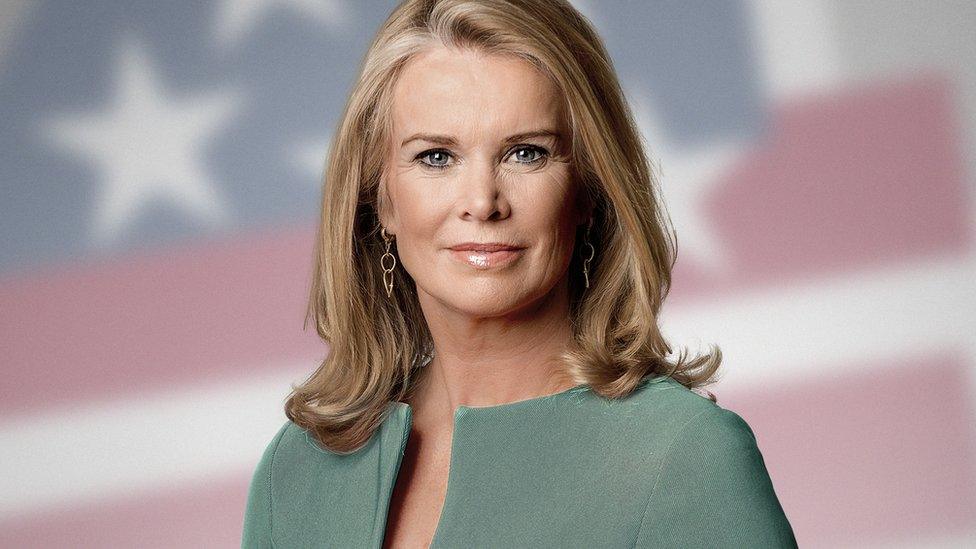

100 Women: Katty Kay on how the 'confidence gap' holds women back

- Published

As part of the BBC 100 Women season, a group of women is gathering in Silicon Valley to create a product in just five days that will attempt to chip away at the glass ceiling.

The BBC's Katty Kay explains why they have every reason to feel confident - but compared to men, they are less likely to feel this way.

Columbia Business School in New York calls it "honest over-confidence" - that easy tendency men have to believe they are more able than they actually are.

In fact, says Columbia, men tend to overestimate their abilities by something like 30%. And it's not that they're faking this confidence, they genuinely believe it.

We women, on the other hand, tend routinely to underestimate our abilities. Our perception of our talent skews lower than our actual worth.

This is what we've dubbed the confidence gap and over the course of a career it can lead to fewer promotions, limited opportunities and less pay.

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. In 2017, we're challenging them to tackle four of the biggest problems facing women today - the glass ceiling, female illiteracy, harassment in public spaces and sexism in sport.

With your help, they'll be coming up with real-life solutions and we want you to get involved with your ideas. Find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external and use #100Women

Read more: Who is on the 100 Women list?

The BBC's 100 Women Challenge is part of a broader movement to close that gap - a gap that has no foundation in reality because there is no evidence that we women are less competent than our male colleagues.

In fact women are doing better than men academically - what we often lack is confidence.

One of the most reliable social studies is to give men and women a scientific reasoning quiz; the women will nearly always say they've performed less well than they actually have, the men will say they've performed better than they actually have. In reality they perform about the same.

How many times have you heard a woman say she was just lucky to get as far as she's got? Or she was in the "right place at the right time"?

Or, in my own case, I've found myself saying, and believing, that the only reason I've been successful in the US is because of my British accent.

It couldn't possibly be that I am good at what I do or that I work hard, right? That would be preposterous!

I'm not Pollyanna. I'm not suggesting that closing this confidence gap would in itself level the playing field between men and women.

There are structural iniquities that confidence alone won't shift. There still isn't equal pay for equal work.

The lack of role models at the top means women can't look up and see an image of themselves as easily as men can. And there is still discrimination.

You face it in your industries, I have faced it in mine.

When a man comments on your physical appearance, the effect is often just to distract from your professional ability.

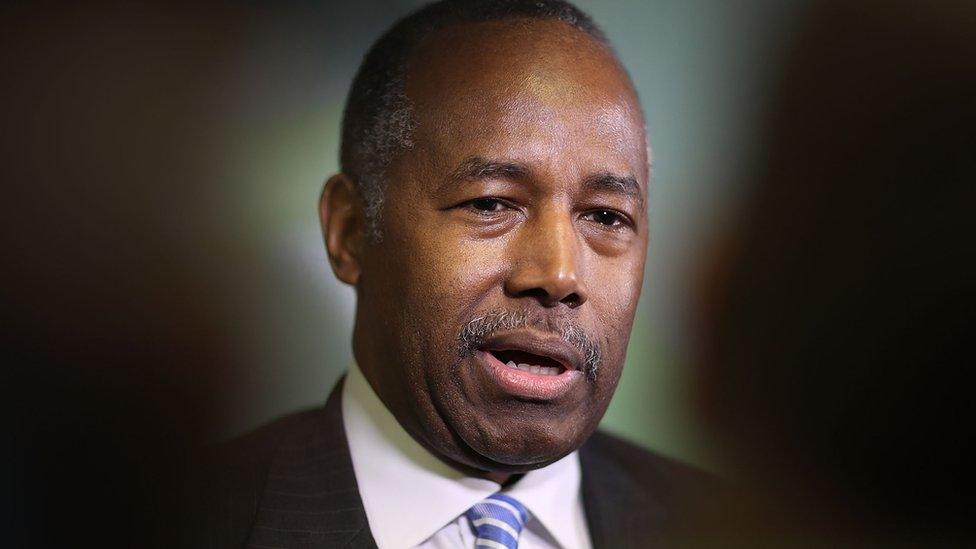

When a man says your microphone should be turned off because you ask a tricky question, as Donald Trump's campaign surrogate, Ben Carson, did to me on a morning TV show, external, it felt to me like a form of "shutting that silly girl up".

The irony that the discussion was actually about harassment of women perhaps did not register with Dr Carson, who is now America's secretary for housing and urban development.

These stubborn realities won't change overnight because we suddenly become more confident. We need policy changes to shift them.

But what attracts me to the study of confidence is that it is something women can address themselves, individually and immediately.

For the book The Confidence Code, that I co-authored with American journalist Claire Shipman, we interviewed dozens of psychologists, business leaders, athletes, military officials and neuroscientists.

We talked to researchers examining confidence in rats - I didn't know there are confident rats and unconfident rats, but I assure you there are.

What we discovered is a pattern that can easily be broken. The confidence gap is due to a noxious stew of perfectionism, risk aversion, fear of failure and over thinking.

Here's an example from my own experience of how it works, and how you can overcome it.

A few years ago I was invited to the White House for a meeting on Middle East policy. I walked into the room of 14 men and two women and realised they were all Middle East experts.

I was the only generalist (and one of only two women).

Immediately I felt like a fraud, I didn't deserve to be there.

When the time came for questions and answers I launched into an internal debate. If I put a question, I imagined, they'd all realise I didn't know as much as them.

I'd probably blush, stammer, sweat and everyone would stare. Eventually I forced myself to raise my hand and get the question out.

And then a remarkable thing happened; the earth did not open up and swallow me whole, the sky did not fall on my head.

But, by asking that one question, I had made easier to handle that situation the next time I was in a high level meeting. I had banked a bit of confidence.

Closing the confidence gap means being honest about your abilities, not constantly undervaluing them.

It means accepting that the odd failure is part of the human condition.

It means letting upsets, criticisms and mistakes go and not clinging to them like a dog with a bone.

And it means not trying to be perfect. Robots are perfect, people are not.

Every time you enter a challenge, like this one for the BBC, you are going outside your comfort zone, taking a risk and closing the confidence gap. And for that, thank you. We need more of you.

- Published1 November 2017

- Published1 October 2017

- Published27 September 2017

- Published2 October 2017

- Published2 October 2017

- Published2 October 2017