100 Women: Football offers girls a shield in Brazil's violent favelas

- Published

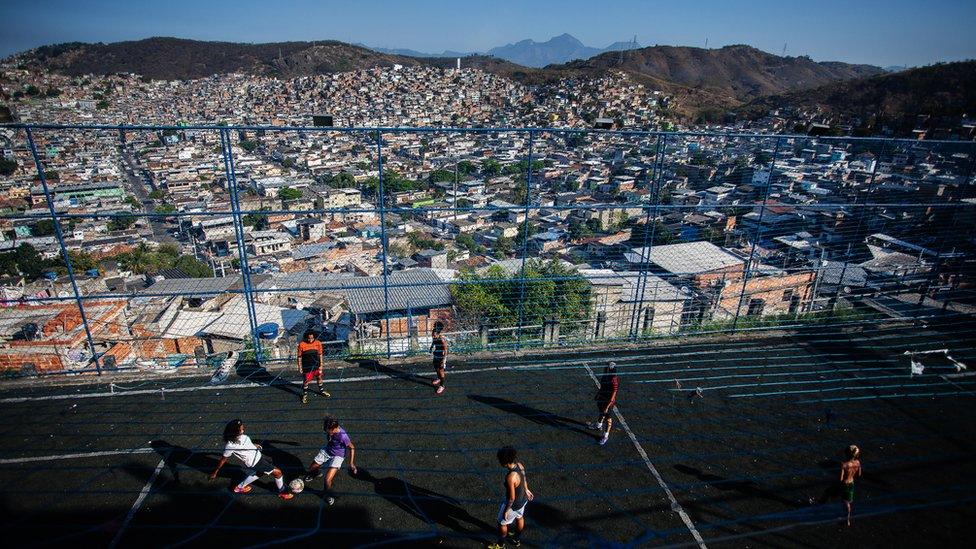

Life in the favelas, home to almost a quarter of Rio's population, is hard.

Brazil's favelas are a battleground between heavily armed drug gangs and the police. The death toll is high, and residents fear being caught in the crossfire.

On average, one Rio resident is hit by a stray bullet every seven hours.

A recent spike in violence comes alongside massive unemployment, as Brazil begins to emerge from the worst recession in its history.

But people have grown used to carrying out their daily lives against a permanent background of violence.

And some young girls have found solace and an escape from their environment through football.

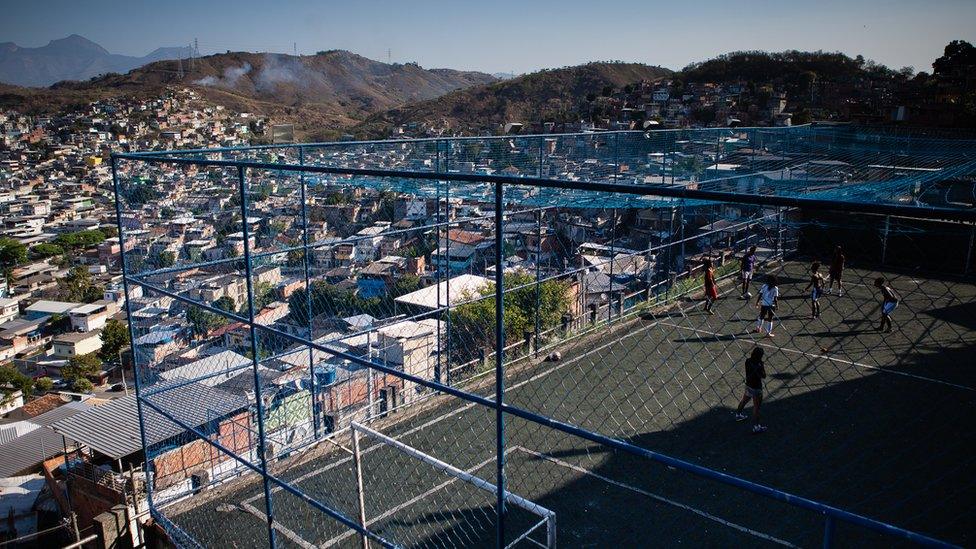

These girls gather in a pitch known to be a safe space in Complexo de Penha, located on the Morro do Caracol hill.

The pitch was built by Street Child United, external, a UK-based charity that gives at-risk young people opportunities through sport. To ensure it was a safe place where children can play without fear, the charity struck a deal - with local residents, the police, and even the gangs - to declare it "off limits".

The girls try to practise football at least once a week, but have had to cancel several sessions because of frequent shootouts between rival gangs and the police.

"The shooting happens several times a week. You never know when the police will start an operation in the favela. Crossfire is a big problem," explains Drika, their coach.

"Sometimes there is no way to get to the pitch, and some other days we have to hide in the locker room because the shooting starts from nowhere. Some kids cry in fear - and it makes my heart ache."

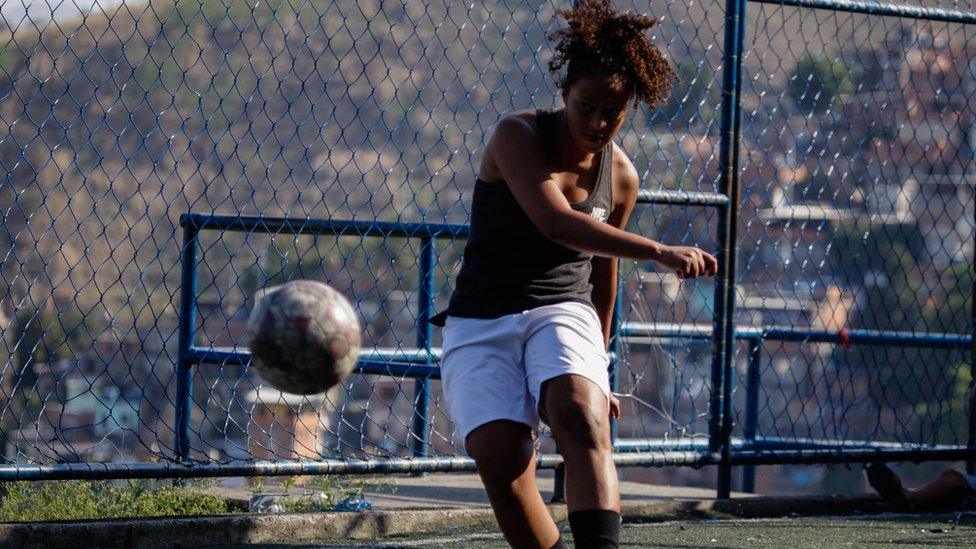

Thammy, 20 years old

Thammy lives in the Favela with her mum and step-father. She dreams of becoming a football coach, so she can earn some money and help her family.

"In soccer my problems disappear - it is a place that I find good energy, it was there that I made friends, and I gained a new family," she says.

"I like football because I believe in the union of people, because together we are strong, our dreams together create more strength. Football helps me take responsibility. I dream of being a physical education teacher, and football only feeds my dream."

Taissa, 16 years old

Thaissa lives with her mother and loves school - but classes are often cancelled due to gunfire. When school is closed, she is stuck helping her mum clean houses.

Thaissa lost a family member in one of the shootings, but did not want to talk about it - and says she prefers to focus on the future.

"I like to play football because it was my dream since I was a kid. I want to become a professional player," she says.

Laryssa, 16 years old

"It is an inexplicable passion, because playing football I feel in another world, I forget my problems, I laugh a lot, I have fun and I make many friendships," says Larissa.

She lives in a house with seven other people, and tries to earn some money helping in carpentry.

Mayara, 17 years old

"Football makes me forget my problems. It is what I love," Mayara says.

Poverty and violence has marked her life. Her mother is unemployed, and her father retired. But Mayara still dreams of a better life for herself and the six other people she lives with, including her grandmother.

Ana Clara, 14 years old

"I always wanted to be a soccer player, since I was a little girl [and] my father took me to play in the sand field on the other side of Penha."

Despite the gunfire, Ana Clara tries to go to school every day, even if she is delayed while waiting for the violence to calm.

Her mother is a hairdresser and her father works in a family clinic. Her dream is to play football professionally and help her family.

Jessica, 16 years old

"Since I played for the first time I fell in love with football," says Jessica, who lives with her mother and four sisters.

Every day, young people are at risk of exploitation and violence from the drug gangs, and from the police when gunfights break out on the streets.

Their coach is Claudianny Drika, part of the 100 women list in 2017, who works to promote inclusion and peace in her community through sports.

Drika was born and raised by her grandmother in Sergipe, northern Brazil. She was one of 10 children, and the family had no electric lights, no TV, and no stove. She had no toys or games.

Football was the one thing that made her happy.

What is 100 Women?

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. In 2017, we're challenging them to tackle four of the biggest problems facing women today - the glass ceiling, female illiteracy, harassment in public spaces and sexism in sport.

With your help, they'll be coming up with real-life solutions and we want you to get involved with your ideas. Find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external and use #100Women

When she was 14, her grandmother died and she went to live with her mother and step-father in Rio de Janeiro - but she was thrown out and ended up "couch-surfing" from place to place. She was eventually taken in by her aunt.

Things began to change for Drika when she started training with the Favela Street Foundation, external - another sporting charity - in one of Rio's largest favelas, Complexo da Penha. At the time, they did not have a pitch like the one the girls use today.

Favela Street was chosen to represent Brazil at the Street Child World Cup Rio 2014, and, with Drika as captain, the team went all the way to the final - where they beat the Philippines 1-0.

Now, she works for Street Child United Brazil and is a model for girls that face same challenges as she did.

She helps up to 300 children a year play sports and learn, reducing their risk of exploitation and abuse, developing their life skills, and improving their education, training, and employment opportunities.

All photographs subject to copyright.

- Published1 November 2017

- Published9 October 2017

- Published9 October 2017

- Published9 October 2017

- Published9 October 2017