How to survive a missile attack: What's the official advice?

- Published

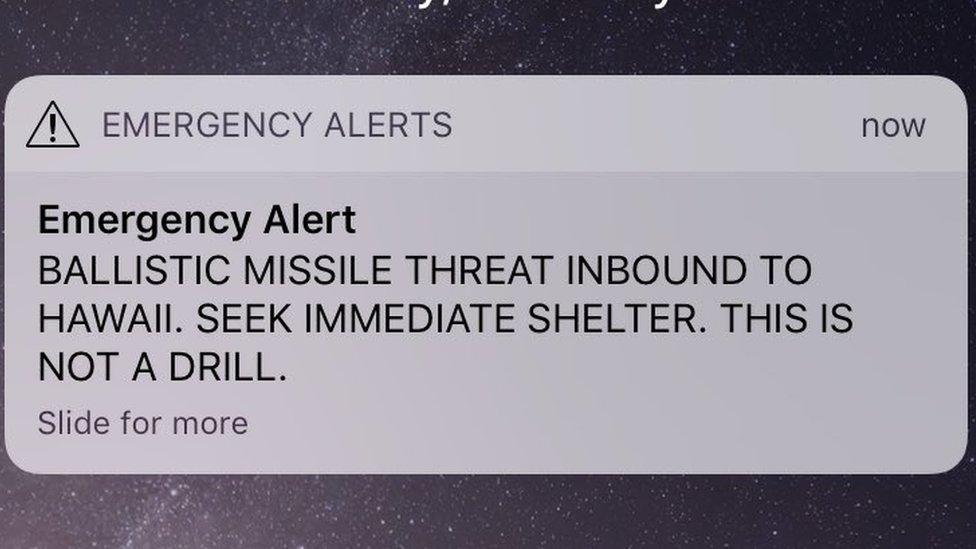

Hawaii's false missile alert: People were warned to take shelter in a warning broadcast

What would you do if a hostile missile was flying towards your country, and you had minutes to take cover?

It's a terrifying prospect, and one the people of Hawaii faced on Saturday when an emergency warning was mistakenly sent telling them, "Seek immediate shelter. This is not a drill".

Many tweeted that they were taking refuge in bathtubs, or even under mattresses.

But what's the official guidance in the event of a North Korean missile attack?

'Get inside, stay inside, stay tuned'

Hawaii has been pondering that question since December, when it restarted monthly tests of its nuclear attack siren for the first time since the end of the Cold War.

The US state, which is about 7,400km (4,600 miles) from North Korea, has been increasingly on edge since President Trump and North Korea's Kim Jong-un began exchanging nuclear threats.

So if the siren goes, what are Hawaiians and visitors meant to do?

Firstly, work out if it really is the missile siren. That signal uses a wavering tone, and is not to be confused with the steady-tone "attention alert" the state uses to warn of natural disasters like hurricanes or tsunamis.

In Hawaii, the sirens for a missile attack and a natural disaster warning sound different (Pictured: A sign in Oahu, Hawaii, after the false emergency alert)

Secondly, don't try to run. You're safer inside the closest, most protective building - below ground if possible, somewhere like a concrete basement.

The goal should be to put the maximum space between yourself and potential nuclear fallout. In Hawaii, social media footage even showed adults guiding children into storm drains. This is not considered safe because of the risk of drowning or dangerous gases being present.

Estimates of how quickly a North Korean missile would hit vary, but last month the Honolulu Star-Advertiser gave an estimate of 20 minutes.

One man told US broadcaster CBS that he started running when the alarm sounded

Hawaii's emergency management agency put out a public service announcement, external in November that advised: "Get inside, stay inside, stay tuned."

So you should also switch on the TV or radio to await information and further instructions.

The US Department of Homeland Security points people to ready.gov, external - a website with guidance on surviving a whole range of crises - from an active shooter, to a volcano, to a pandemic.

In case of a nuclear blast, it says:

"An underground area such as a home or office building basement offers more protection than the first floor of a building."

"The heavier and denser the materials - thick walls, concrete, bricks, books and earth - between you and the fallout particles, the better."

It also has tips for people keen to plan for the extremely unlikely event of a nuclear missile attack:

"Find out from officials if any public buildings in your community have been designated as fallout shelters."

"If your community has no designated fallout shelters, make a list of potential shelters near your home, workplace and school, such as basements, subways, tunnels..."

Build a disaster supplies kit, external with packaged food, water, a working radio and other essentials.

And elsewhere in the world?

Hawaii isn't the only place to make headlines over a emergency alert.

On the small Pacific island of Guam, home to a strategic US airbase, residents feared the worst for 15 minutes in August 2017 when two radio stations mistakenly broadcast an urgent warning.

North Korea claims its nuclear weapons could strike the US territory at will - and the same goes for Japan and South Korea.

Both have anti-missile defence systems and emergency alerts.

South Korea's capital, Seoul, lies just 56km (35 miles) from the North Korean border, and national evacuation drills are held regularly.

North Korea's Kim Jong-Un (2nd R) inspects the test-fire of an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile in July 2017

Japan has stepped up preparedness since North Korea repeatedly fired missiles over its territory in 2017, a move Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called an "unprecedented" threat.

During a North Korean missile test in August, a safety warning urged citizens on Japan's northern island of Hokkaido to take shelter in "a sturdy building or basement".

In nationwide advice on how to survive a nuclear attack, the Japanese public were told that if a missile landed nearby, they should cover their mouths and noses and run away. Anyone indoors should stay away from windows to avoid injuries from shattered glass.

A system called J-Alert exists to warn the Japanese of any incoming attack through TV, mobile phones, radio and outdoor loudspeakers.

And on Hokkaido, officials have gone the extra mile: a colourful manga comic was recently published showing children hiding under their school desks, a jogger taking refuge in a public toilet, and farmers lying face down in the fields.

Japanese people practising nuclear attack drills

- Published14 January 2018

- Published14 January 2018

- Published3 January 2018

- Published27 April 2017

- Published15 September 2017

- Published15 September 2017

- Published9 October 2016

- Published7 August 2017