How a 'concrete floor' could get more women into power

- Published

Women are largely under-represented in governments and at the top of big businesses around the world. Could the answer be as simple as a 'concrete floor' created by those with the power to change things?

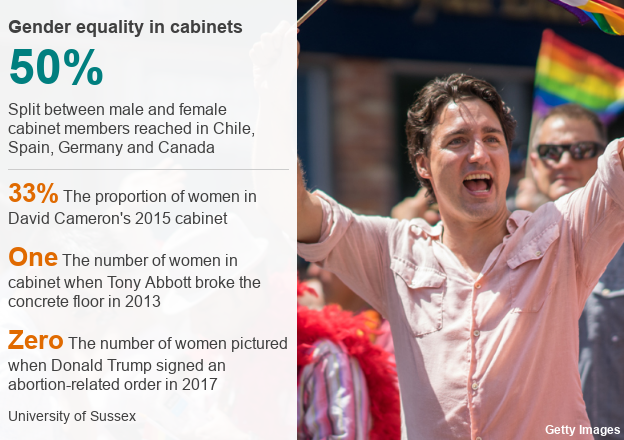

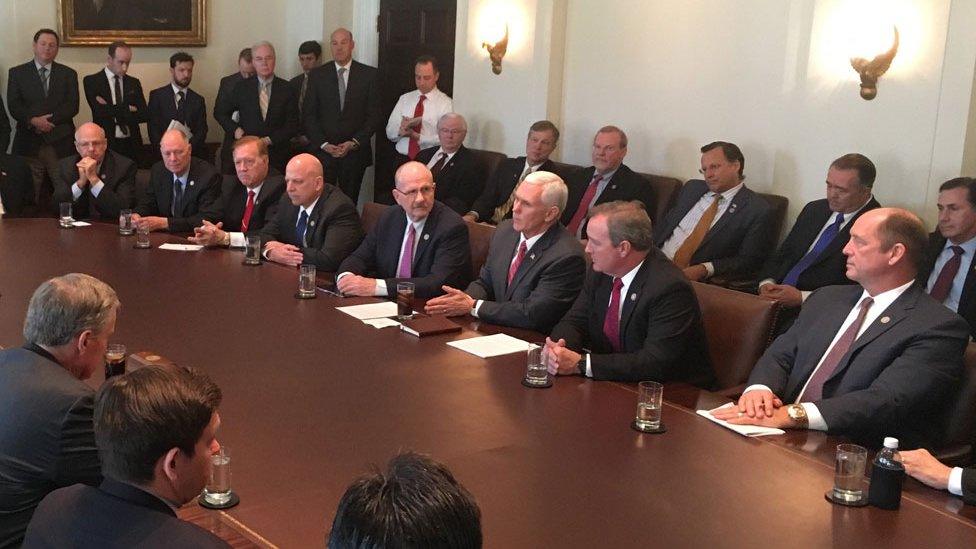

Critics were quick to notice the irony of an order on abortion funding being signed by US President Donald Trump as he sat at a desk surrounded by men.

The sense that women are too often cut out of such political decisions prompts scrutiny of the gender of new ministers. And there is frustration when male business leaders claim their female colleagues "don't want" to be on the board.

Often, it is thought quotas are the best way to improve gender equality, but a study of ministerial appointments to governments in seven countries, external suggests a personal pledge by those in charge may be more important.

In each country we looked at, once the number of women appointed to cabinet reached a certain threshold, it sometimes dipped but rarely fell below that level again.

We call this the "concrete floor" - something that might support women both in politics and business as they attempt to break through the "glass ceiling" we so often hear about.

US President Donald Trump signing the abortion-related executive order in the Oval Office

Our study - which included Australia, Canada, Chile, Germany, Spain, UK and US - covered the period between the point at which the first female minister was appointed in each country and the end of 2016.

After many decades of exclusion from cabinets, women's presence shot up sharply in some countries.

In Canada, Chile, Germany and Spain an equal number of male and female ministers was seen at least once.

In Australia, the US and the UK, there was also a rise in the number of women ministers, but it happened more slowly and has not risen above about 30%.

In every case one of the biggest forces for change was not a quota, but a pledge from an aspiring prime minister, or president, to improve gender equality.

The first pledge we found came from Bill Clinton. In 1992 he made a campaign promise to appoint a cabinet "that looks like America", external, and then tripled the share of women in cabinet from 7% to 21%.

In Spain, Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero pledged and delivered a parity cabinet in Spain, external in 2004. Michelle Bachelet appointed a parity cabinet in Chile, external in 2006, as did Justin Trudeau in Canada in 2015.

In the UK, David Cameron promised in 2008 that a third of ministers would be women, external in any future government. He didn't deliver this for the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, but the 2015 Tory majority government had 33% women.

For Zapatero, Bachelet and Trudeau, the pledge came from feminist conviction. David Cameron was committed to gender equality although he was also under pressure to make the party more attractive to female voters.

Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero with the eight female members of his cabinet in April 2004

Pledges have come from leaders on the left, centre and right, and from male and female leaders.

Ironically, men may be more likely to be congratulated for pushing for change than women.

But all leaders who move towards gender equality tend to be applauded and those who deliver parity - like Zapatero and Trudeau - most strongly praised.

None has seen their careers suffer as a result.

It appears to be the case that a pledge is powerful because those who make it are in a position to ensure change happens.

And it is clear that it is they who will be held accountable if they fail to act.

Tony Abbott is the only leader to have broken the concrete floor established by his predecessors

To avoid losing public support, those who follow these leaders may feel obliged to follow suit. Expectations about gender representation in that country and across all parties appear to shift as a result.

The next political leaders may not achieve the same levels of equality, but we found that representation rarely drops to where it was before.

The term "concrete floor" captures the way progress becomes locked-in over time. It is difficult to break back through it.

For example, when Zapatero left office in Spain, women's representation fell from 56% to 30%, but never as far as 20% - the level at which it had been.

And in the US, after Bill Clinton's second term, women's representation went down from 28% to 20% - still well above the previous 7%.

We found just one example of a broken "concrete floor" up to the end of 2016.

In 2013, Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott was strongly criticised for cutting the number of women in cabinet from three, down to one.

In fact, he was delivering on another pre-election pledge that all of his frontbenchers would do the same job in government as they had done in opposition. And one female member of his shadow cabinet team lost her seat.

President Trump's first cabinet appointments in 2017 also saw him break the "concrete floor" in the US, but he has since appointed another female minister - returning things to where they were under President Obama.

More like this:

Pledges and "concrete floors" are also relevant beyond politics - focusing minds on problems like leadership and pay inequality.

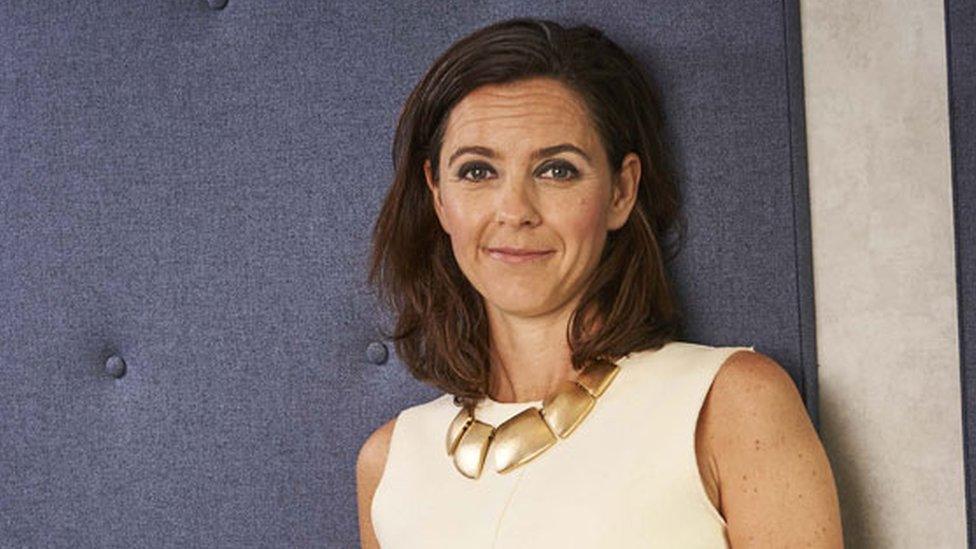

For example, responding to broadcaster Channel 4's 24.2% gender pay gap, chief executive Alex Mahon said she wanted to see an equal number of men and women among the top earners by 2023.

Taking responsibility, she said: "By setting such a clear target I have to bring on or progress a whole load of women."

Channel 4 boss Alex Mahon has made a personal pledge to tackle the company's gender pay gap

And in response to the BBC's 9% gender pay gap, director general Tony Hall made what he called a "big, bold commitment" to close the gender pay gap by 2020.

It will be interesting to see how effective these pledges turn out to be.

Using pledges to ensure an ever-rising "concrete floor" does not mean that more familiar devices like quotas and all-women shortlists are redundant.

For example, they can boost the number of women in parliament, where the appointment process involves persuading multiple selectors to choose women: first party selectors and then the electorate.

But the reality is that there might be a simpler and faster alternative - getting those in power to make a pledge.

Correction 5 June 2018: An earlier version of this story stated that Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero delivered parity in Spain in 2008 and that Michelle Bachelet did the same in Chile in 2009. In fact, Zapatero first pledged and delivered parity in 2004, while Bachelet made the pledge in 2005 and delivered it in 2006. The piece also referred to Donald Trump signing a bill on abortion, rather than an executive order.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Prof Claire Annesley, external is professor of politics at Sussex University. She worked on Cabinets, Minsters and Gender, external with Susan Franceschet, external and Karen Beckwith, external.

Their research compares the number of women appointed to the first cabinet after an election in each of the seven countries. It does not count those appointed in reshuffles. To allow comparisons between countries, only ministers who were part of the core cabinet team were included, not cabinet level officials such as the US Ambassador to the UN, or junior ministers in the UK.

Follow Claire Annesley at @claireannesley, external.

Edited by Jennifer Clarke and Duncan Walker

- Published24 March 2017

- Published24 January 2017

- Published15 July 2014